New art exhibition ‘Dear Black People’ puts trauma and triumph on display

The glow of a vibrant, multi-shaded watermelon shines through the glass of a building sitting on the corner of Centennial Olympic Park Drive and Chapel Street.

Hypnotizing in its vibrancy, the fruit in a 2-set collection creates a vivid contrast as it’s lugged over the shoulder of a man — only seen from the back — with stark white, textured hair wearing a lavish blue suit jacket. The watermelon is so rich in color that the taste transcends the painting. It is handled with care and features a gentleman espousing sophistication.

To the left, the gentleman is shown in a full-body, frontal shot. Decked out in a full suit and tie, he manages his prize on one shoulder while sporting a briefcase in the other hand. Possibly more exuberant than the previous painting, a symbolic color scheme gives a nod to the anti-imperialist fight of West African nation Burkina Faso.

Part of a new exhibit at ZuCot Gallery, “Dear Black People…A Love Letter” features elements of Black American culture generationally woven in and out of time. The collection is an ode to a community that has persevered through systems of oppression, reminding Black people their innovative strength is limitless.

“The theme behind this entire show I titled ‘Dear Black People…A Love Letter,’ and ... I’m basing it off of what’s going on in the country right now and what I feel that we need as a reminder,” explained ZuCot Gallery Managing Partner and exhibit curator Onaje Henderson. “To remember that we have been under darker clouds and we thrived under every single one.”

The outward-facing watermelon paintings set a strong tone for the collection. According to the ZuCot Gallery, they target dehumanizing stereotypes and racist caricatures of African Americans following the Civil War.

Often misrepresented in history, Black watermelon farmers managed to economically self-sustain after emancipation. However, mainstream marketing tactics weaponized the watermelon so that it was viewed as a demeaning racist trope of Black people.

“The resulting image became so deeply ingrained that, even today, some African Americans avoid eating watermelon — or being seen with it — out of fear of judgment or ridicule,” according to image narratives provided by ZuCot.

In “Dear Black People…A Love Letter,” the watermelon is a trophy reclaimed for Black American pride.

The exhibit is softly divided into sections of past, present and future.

However, the collection reminds viewers that the African American timeline is fluid but that segments are borrowed and lent throughout more than 400 years of cultural lineage.

“This show goes throughout the history of past, present and future, how we’ve always thrived,” Henderson said in an interview. “We’ve always been here.”

Visitors of the exhibit begin in a period of social demonstrations. Colorful marches with protest signs set a mood of resistance, vigor and unity. The distinct faces of a Civil Rights-era community illustrate a range of people who have been affected. Profiles of Nikki Giovanni and James Baldwin show Black women and men’s fight for humanity. In some paintings, Black men don moderately curated outfits and guard Black humanity with heavy-barreled rifles.

“There was a group of men called the Deacons for Defense and Justice during the Civil Rights Movement. They were not nonviolent,” Henderson explained. “They had chapters all over the South. These brothers carried guns. When the Klan and people like that tried to threaten their neighborhoods, (the Deacons) would go get a chair from the church and still sit and wait for them.”

Henderson said artist Aaron F. Henderson, his father, posed the question of whether or not groups like the Deacons, who were ex-military members, should make a comeback.

“(The artist is) asking a question, ‘Is it time for the Deacons to come back to protect our community again?’” Henderson said. “It’s now; it’s current. It’s not supposed to be back in the day.”

The collection of Deacons for Defense paintings serves as a gateway to the immediate present, where images confronting assimilation and urban marginalization come into play.

“Odyssey Untitled” addresses heritage reclamation as African Americans attempt to refind themselves after dealing with the scars of the transatlantic slave trade.

“Liberty Variant” and “Capital Wiz” paintings show the cracks in America’s foundation, legacies built off the backs of enslaved labor.

In “Nepotism Deferred,” a Black child sits on a knobless door with no key. But somehow he has managed to make his way over the door and lowers a rope for others to climb up with him.

“There’s no key, no opening,” Henderson said. “Well, this is how most things are here for us, right? It’s saying if you can get your foot in that room, you throw that rope back down so the next person climbing will get in that room too. That’s our nepotism.”

Then, a jarring image of a Black body being consumed by white, fleshy hands gives electrifying bolts of violence. The body yells in self-defense to stave off the colonization, but it seems almost inevitable.

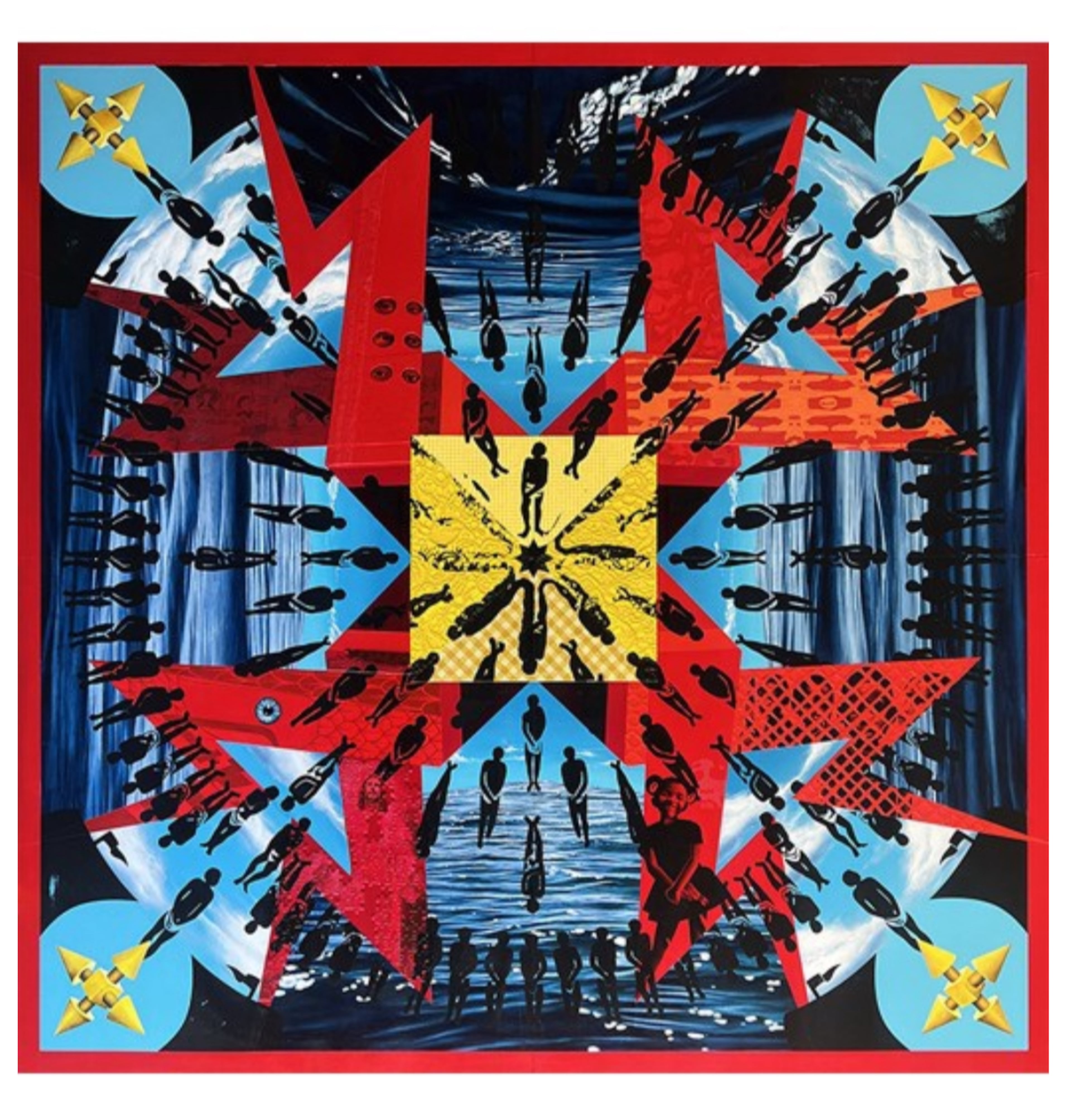

The second floor of the exhibit moves into a time-traveling stratosphere, where moments of Black history seem to echo in the future. With Afrofuturism on full display, the room questions the relevance of past revolutionary tactics as Black astronauts travel through space with constellations embedded on actual blueprints. Pathways of the underground railroad searing across the cosmos call to question the next path to freedom African Americans will take.

Nestled in the artistic neighborhood of Castleberry Park, ZuCot Gallery, one of the largest Black-owned art galleries in the southeast, was founded in 2009 by Troy Taylor, Henderson and his brother Omari Henderson.

Henderson said the goal is to get more Black people to accept artwork as part of their culture and invite it into their homes without having the white gaze dictate what constitutes quality and worth.

He said making sure the art centers on Black narratives is what makes ZuCot an unapologetically Black art space.

“Everyone’s welcome to come in. At the same time, (Black people are) going to be the center. We go through it, whether it be our stories, our artists or just our perspectives,” Henderson said. “It’s a reflection of who we are.”

With the latest exhibit, he specifically wanted the Black community to know that it’s been curated out of admiration.

“It was first going to be called ‘Dear Black People,’ and I added ‘...A Love Letter’ because I wanted to make sure they understood it was in love.”

ZuCot Gallery’s “Dear Black People...A Love Letter” exhibit is on display through Oct. 4. Admission is free.

“Dear Black People...A Love Letter”