‘Joy Goddess:’ Former Atlantan writes on power and grace of A’Lelia Walker

On Aug. 19, 1931, poet Langston Hughes sat inconsolable in the pews of Harlem’s Howell Funeral Chapel.

At the lectern, Edward Perry recited a poem written for the occasion by Hughes to the 350 invited mourners at the funeral of A’Lelia Walker — one of the most glamorous and influential Black women of the Harlem Renaissance — who had died days earlier.

“She did not die at home / In her bed at night,” Hughes wrote. “She died where laughter was, And music, and gay delight.”

Nine years later, in his autobiography “The Big Sea,” Hughes immortalized Walker as “the joy goddess of Harlem’s 1920s,” recalling her legendary parties “filled with guests whose names would turn any Nordic social climber green with envy.”

A’Lelia Walker — the only child of hair care mogul Madam C.J. Walker — was one of the wealthiest Black women in American history, having helped build and later inherited her mother’s beauty empire.

And she hosted gatherings that rivaled any in Black social life.

In the 1910s and 1920s, A’Lelia Walker’s guest lists sparkled with Harlem Renaissance luminaries, international celebrities, heads of state and emerging queer creatives.

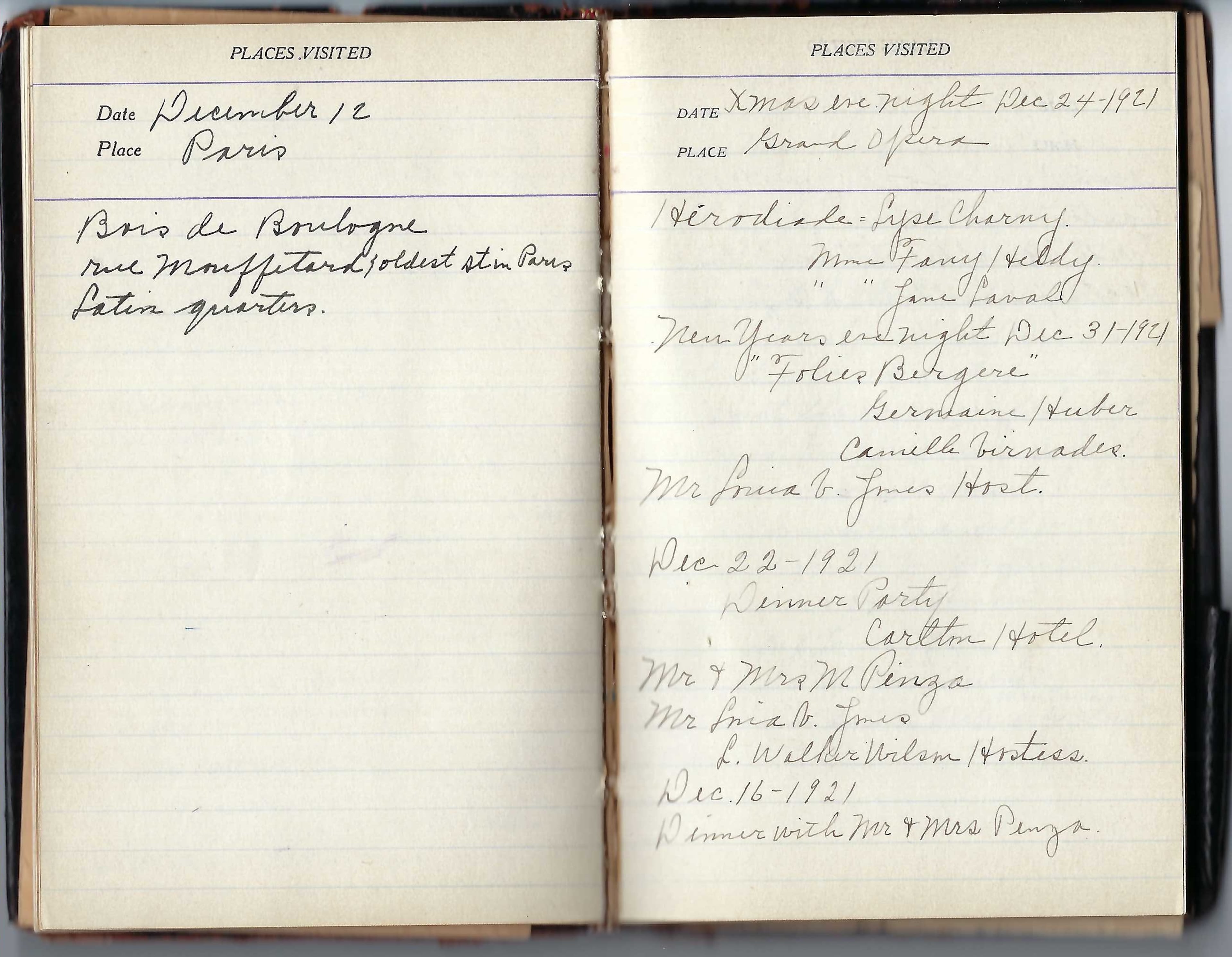

When she wasn’t hosting landmark soirees in one of her elegant townhouses or her mother’s Irvington, New York, mansion Villa Lewaro — designed by Vertner Woodson Tandy — she was managing the expansive family empire or voyaging across Africa, Europe and the Caribbean.

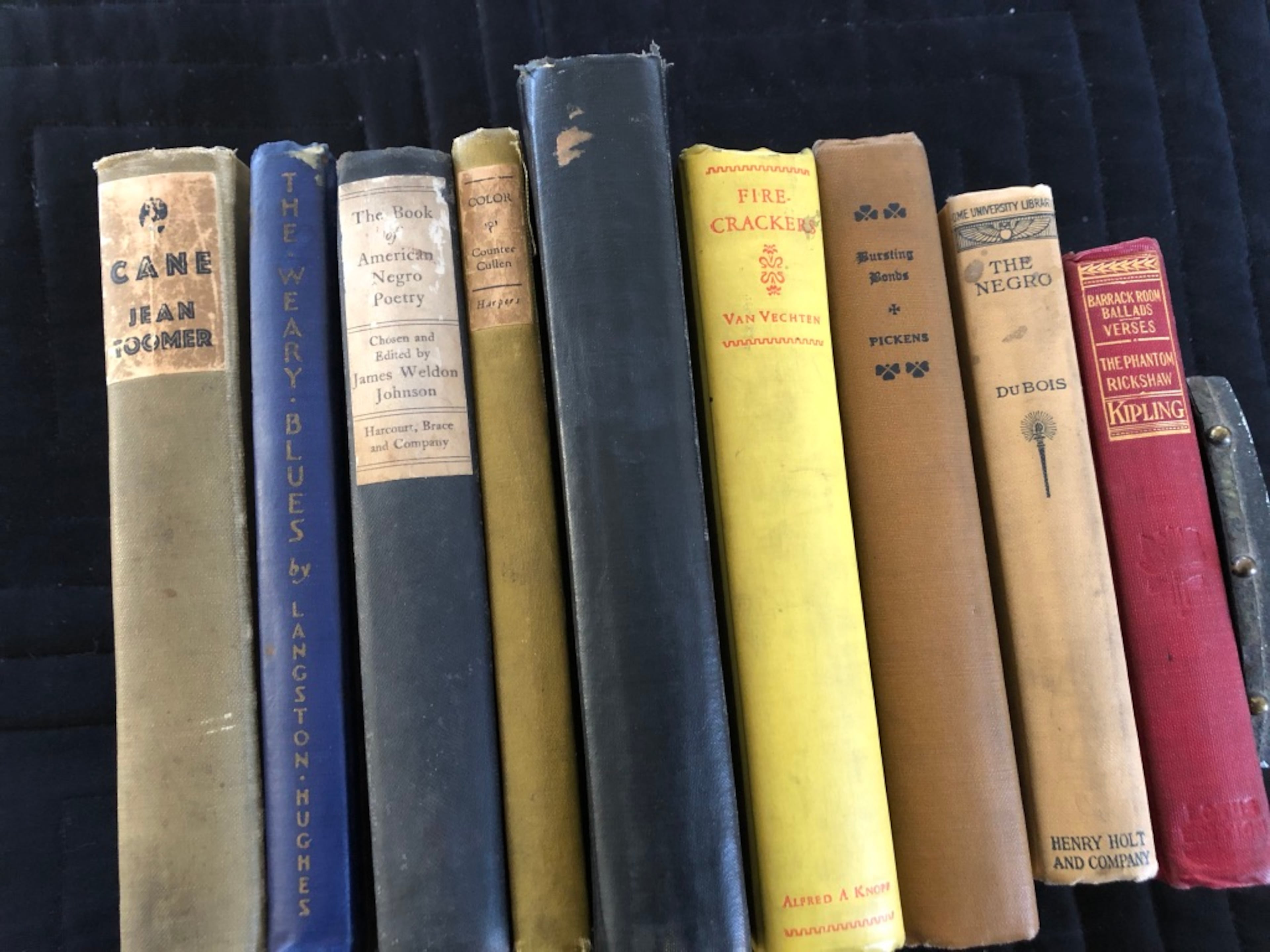

Her famed Dark Tower — a lavish salon named after a Countee Cullen poem about dignity, justice and equality — invited downtown intellectuals to mingle with uptown artists.

“She created a space where Langston Hughes could rub elbows with queer artists, European intellectuals and Black businesswomen,” said A’Lelia’s great-granddaughter and biographer, A’Lelia Bundles. “She brought people together who would never have otherwise met.”

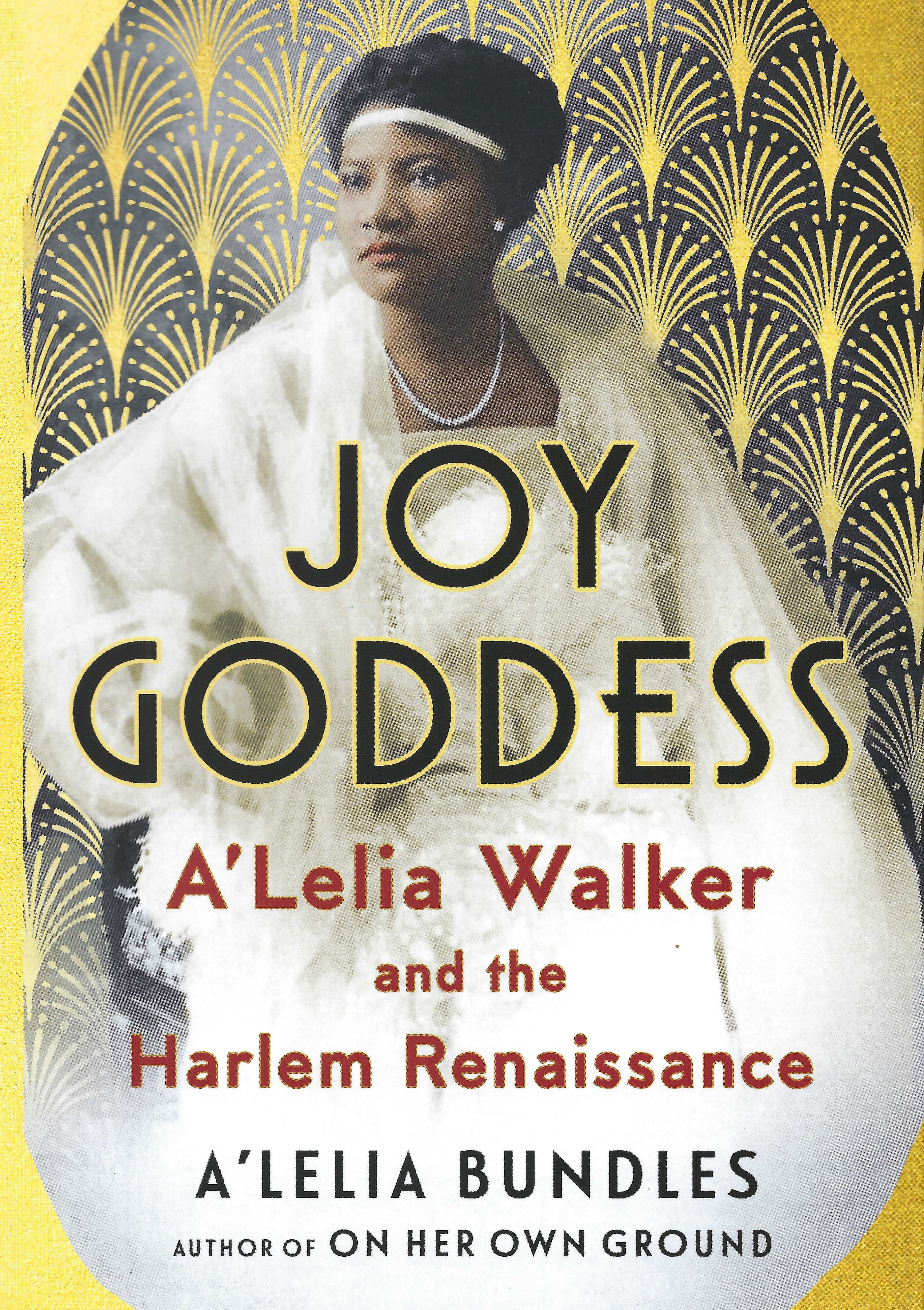

All of that created what Bundles calls “a potent and unprecedented cultural mix” and informs her stunning new biography, “Joy Goddess: A’Lelia Walker and the Harlem Renaissance.”

It manages to be both scholarly and intimate in its scope.

“She was always portrayed as this extravagant party girl,” said Bundles, a veteran journalist who worked in NBC News’ Atlanta bureau in the early 1980s. “But I knew from the beginning that there was a complexity there that I wanted to explore.”

This weekend, Bundles returns to Atlanta to speak at the sold-out 21st National Book Club Conference, the largest annual literary event celebrating Black authors and readers in the U.S.

For Bundles, the decision to write “Joy Goddess” was personal, professional — and inevitable.

Growing up in 1950s Indianapolis, Bundles often accompanied her mother, A’Lelia Mae Perry, to the Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company, where Perry served as president.

At home, she ate on Walker-monogrammed china and learned to play piano on an instrument that once sat in the family’s mansion.

“I knew we were connected to somebody important,” Bundles said. “But we didn’t sit around the table talking about her. My mother let me discover that history on my own.”

While Bundles has written four books about the family’s towering matriarch, she was always more fascinated by her namesake, A’Lelia Walker.

Bundles’ “On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C.J. Walker‚” which was later adapted to the Netflix series, “Self Made,” was initially intended to be a dual biography of C.J. and A’Lelia Walker.

“But I realized A’Lelia needed her own book,” Bundles said.

“Joy Goddess” brings A’Lelia Walker into clear focus and out of her mother’s long shadow.

Madam C.J. Walker rose from poverty — working as a widowed washerwoman for barely a dollar a day — to become one of America’s first self-made female millionaires.

Her only child, A’Lelia, born in 1885, shared in that ascent.

As Bundles writes, theirs was a “fire and ice” relationship — shaped by fierce devotion and shared ambition as they reimagined early 20th-century Black womanhood as stylish, self-sufficient and unapologetically free.

Through their hair care empire, they redefined Black beauty standards and created generational wealth and opportunity for thousands of African American women.

“There were times when A’Lelia Walker made me mad,” Bundles admitted, recalling how A’Lelia pressured her adopted daughter — Bundles’ grandmother, Fairy Mae Walker, a Spelman Seminary graduate — into an unwanted marriage. Later, A’Lelia offered little sympathy during an abusive relationship. “I wanted to write that. I wanted to show what really happened.”

That also meant correcting the record that portrayed A’Lelia as shallow and out of touch — often dismissed by historians as frivolous or lacking business acumen.

“None of that was true,” Bundles said. “And those stories got repeated in dozens of books.”

Bundles drew on oral histories, personal letters, photographs, receipts, guest lists, travel diaries and family archives — what she calls “deep research, not secondary sources” rooted in original documents.

What emerged was a portrait of a cultural convener who, behind the joy, endured pain and isolation.

Walker had chronic health issues and failed marriages. And despite her wealth, certain circles of the Black elite — who clamored for Walker’s products — shunned the family for their dark skin and humble origins.

While commenting on her “fine physique,” W.E.B. Du Bois called Walker “a person of infinite pathos” whose life “was a series of pitiful disappointments.”

“The irony of ‘Joy Goddess,’ is there was joy, but there was also betrayal, heartache and loneliness,” Bundles said. “At first, she was just a fascinating figure. Then, she became human.”

Still, in an era defined by Jim Crow, Walker used her influence to carve out spaces of safety and celebration as a form of resistance.

“She didn’t wake up every day thinking, ‘I’m going to resist racism,’” Bundles said. “But she did wake up thinking: ‘How can I be happy? How can I help others be happy?’”

In that, she succeeded.

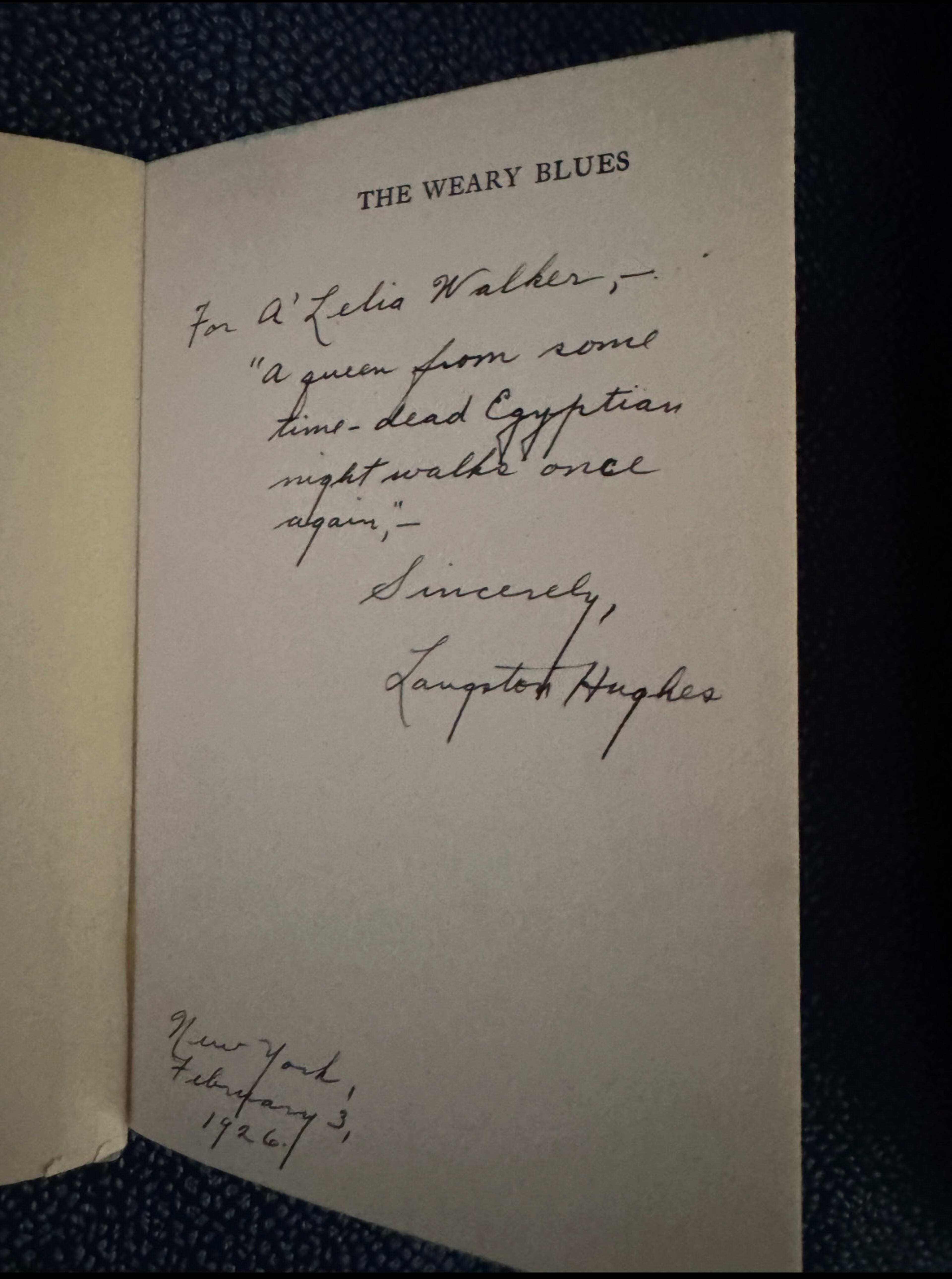

In her personal library, Bundles keeps a signed copy of “The Weary Blues” — a gift from the poet Hughes to A’Lelia.

Borrowing a line from his poem, “When Susan Wears Red,” Hughes wrote:

“For A’Lelia, — ‘A queen from some time-dead Egyptian night walks once again,’ — Sincerely, Langston Hughes. (New York, February 3, 1926.“)

National Book Club Conference

The sold-out 21st National Book Club Conference will be held Friday-Sunday at the Westin Buckhead Atlanta. Featuring more than 40 authors and speakers, and 400 avid readers from across the country, it is the largest annual literary event featuring Black authors and readers in the country.

The conference was founded by former AJC sports writer Curtis Bunn.

Aside from Bundles, this year’s lineup of authors and speakers will include Michael Eric Dyson, Daniel Black and Alencia Johnson.

For more information, go to nationalbookclubconference.com.