She lives in my lap: How the divine feminine inspired the music of Outkast

I’ll be in the room when Outkast walks onto that Rock & Roll Hall of Fame stage on Nov. 8. So will the South, the spirit of Rico Wade, the Dungeon Family collective and metro Atlanta communities (especially the SWATS, East Point, College Park, the Eastside and all the zones).

But those who know will also feel the presence of the women who raised, loved, checked, managed and inspired Outkast.

Few artists have captured Atlanta’s dual nature —the poetic and the profane paired with the street and the sanctified — like Outkast. And nowhere is that duality clearer than in how they write about and imagine the feminine.

In fact, their catalog — even with its misogynistic moments — is a love letter to the feminine. The sacred, the sensual, the spiritual, all remixed through Southern manners and intergalactic imagination: That is ’Kast in a nutshell.

Peaches

The Southern Black woman, in particular, has been a muse and matriarch in the Outkast imagination since Dee Dee Hibbler-Murray, a.k.a. “Peaches,” opened up “Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik” in 1994. She’s the first voice heard on their debut album.

We heard from a different peach — Myrna “Screechy Peach” Crenshaw — on their 1996 follow-up, “ATLiens,” where she and Joi Gilliam sing-pray on “You May Die (Intro)”:

“You can be sure. Some go low to get high. You may hurt ‘til you cry. You may die,” before declaring, “Keep on trying … ‘til there’s summer in the city.”

Both albums begin on maternal frequencies that root their world in care and accountability, a sensibility that runs through songs like “Git Up, Git Out,” where the CeeLo Green refrain sounds like something a mother or auntie would say: “Get focused, do better and … don’t spend all yo’ time tryna get high."

That moral grounding is equal parts church and front porch. It became one of the approaches taken to how they navigated desire, faith, and femininity in their music and art.

Big and Dre have never fully escaped the contradictions of hip-hop’s gender politics; few of their peers did. They also never drowned in them the way songs like “We Luv Deez Hoez” might’ve made it seem.

The track’s title, as far as I’m concerned, has some truth in it. The lyrics may be satirical, but there’s honesty in the hook’s declaration.

“From the weave to the fake eyes, to the fake nails down to the toes … ,” it goes. It’s humor with a mirror, not a manifesto. The problem, though, is that the mirror tilts. It reflects a culture of performance while projecting that critique onto “deez hoes” themselves.

That tension is the paradox and perhaps the genius of Outkast’s innovation. They flirted with the language of the player but rarely surrendered fully to its logic.

All the Players. All the Hustlers.

In the South, the player isn’t merely a womanizer; he’s a performer of cool. The keeper of confidence. Big Boi gave that archetype a conscience.

Even when “Daddy Fat Saxxx” leaned into swagger, there was always awareness behind the boast. In some songs, his women are dance partners (“The Way You Move”). Sometimes they hold down the hook, as is in “Reset.”

Women are never arbitrary in their world. Outkast compartmentalizes them as lovers, mothers, creatives, even menaces, but always with intention.

They assign women roles that hold symbolic weight, even when those roles are flawed or confined. Take “Suzy Skrew” and “Sasha Thumpa” from “Da Art of Storytellin’ (Pt. 1).” The story, about fleeting pleasure and loss, reveals how the women in Outkast’s universe often carry the moral weight of the narrative, even when they’re trapped in its margins.

That tension surfaces on “Jazzy Belle,” a play on the female archetype of the Jezebel. The song is Outkast critiquing the economy of toxic relations — even as they participate in them.

In the song, André 3000 moves from reverence to frustration, praising women then recoiling their sexual autonomy, particularly with the line “’Cause most of the girls that we was liking in high school, now they dykin’” before Big Boi begins his final verse, adding “Have no mercy for the disrespectful ones, some, be hanging around the crew looking for funds … ”

Even in that unease, they hint at a truth rarely acknowledged in hip-hop: The pursuit of power and validation cuts both ways, and the women in these stories are navigating the same game, just playing different positions.

It’s not absolution. It is awareness treated as the frame, the reflection and sometimes the friction.

13th Floor

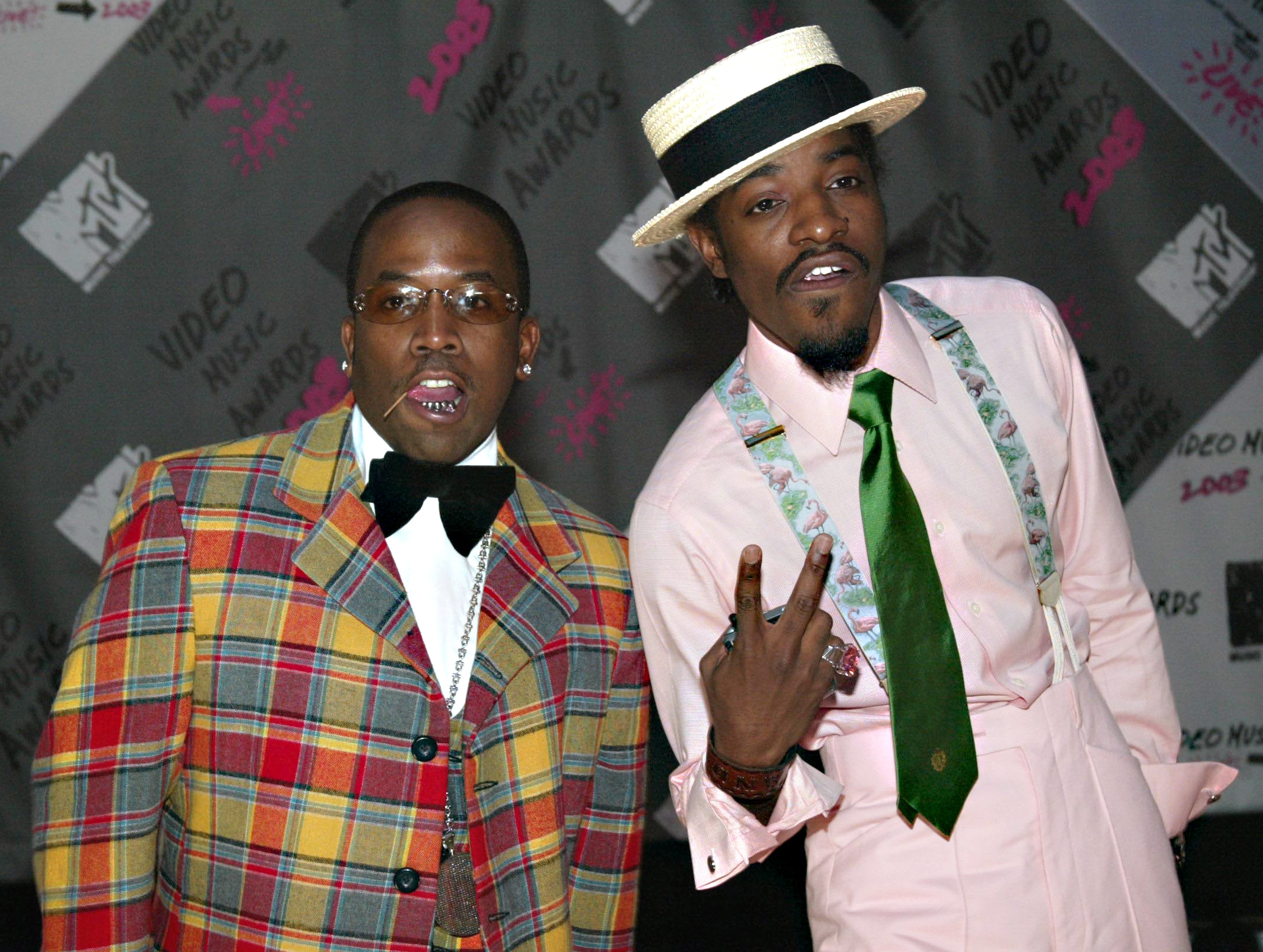

By “ATLiens," Big Boi had taken on a more defined persona of “the player.” The hustle and humor that once sounded like teenage confidence evolved into a grown-man philosophy of survival. We hear them maintaining composure, strategy and pride in being from a place that demanded all three.

On the album’s title track, when he rhymes “I’m cooler than a polar bear’s toenails,” Big Boi’s wit, self-possession and Southern charm crystallize into signature form. We hear it again on “Aquemini’s” “SpottieOttieDopaliscious,” where the player-storyteller turns lover and father figure, grappling with the real-life weight of connection and consequence.

By “Stankonia," that awareness deepens on “Ms. Jackson,” a love song built on accountability where two fathers learn to apologize for their parts in bad break-ups. And by “Speakerboxxx,” the persona matures into partnership and pressure. On “The Rooster,” Big Boi raps through the strain of family life as his confidence cracks under domestic tension.

Together, they mark his shift from performance to principle — from looking the part to living it.

André began to embrace the persona of “the poet.”

You hear it on “ATLiens” songs like “13th Floor / Growing Old,” where he trades bravado for introspection: “I bet you never heard of a playa with no game. Told the truth to get what I want, but shot it with no shame. Take this music dead serious, while others entertain … ”

By the time 3000 got through “Aquemini” and “Stankonia” to “The Love Below,” he had stretched the frame of masculinity until it became something more fluid and cosmic. He oscillates between lover and friend, gently pairing his masculine with the vulnerability of the feminine.

On “She Lives in My Lap (featuring Rosario Dawson),” he absolutely goes there, singing about love from a place of wonder, insecurity, even fear: “You’ve got me open wide (I love you), Please come inside (baby), it’s yours, I’m yours for sure, play baby play.”

His falsetto voice on “Prototype” turns love into a kind of discovery, wondering aloud, “I hope that you’re the one,” while “Pink & Blue” is his vulnerability made audible, celebrating the joy of women as both inspiration and equal. Then, “Roses” calls out the woman who thinks she’s perfect, but the song’s humor ultimately exposes the fragile pride of the men judging her.

The ladies love them both for it.

The contrast sharpened their chemistry. Together, Outkast created a sonic yin and yang, sidestepping the cruelty of misogyny that too often defined full-length albums in that era. That’s not to say they were immune to it. Early tracks like “Hootie Hoo” or “Mamacita” reveal moments when their curiosity about women slipped into critique or conquest. But what separates Outkast is how they grew past those impulses. This self-awareness, sharpened over time, keeps their catalog from collapsing into disrespect.

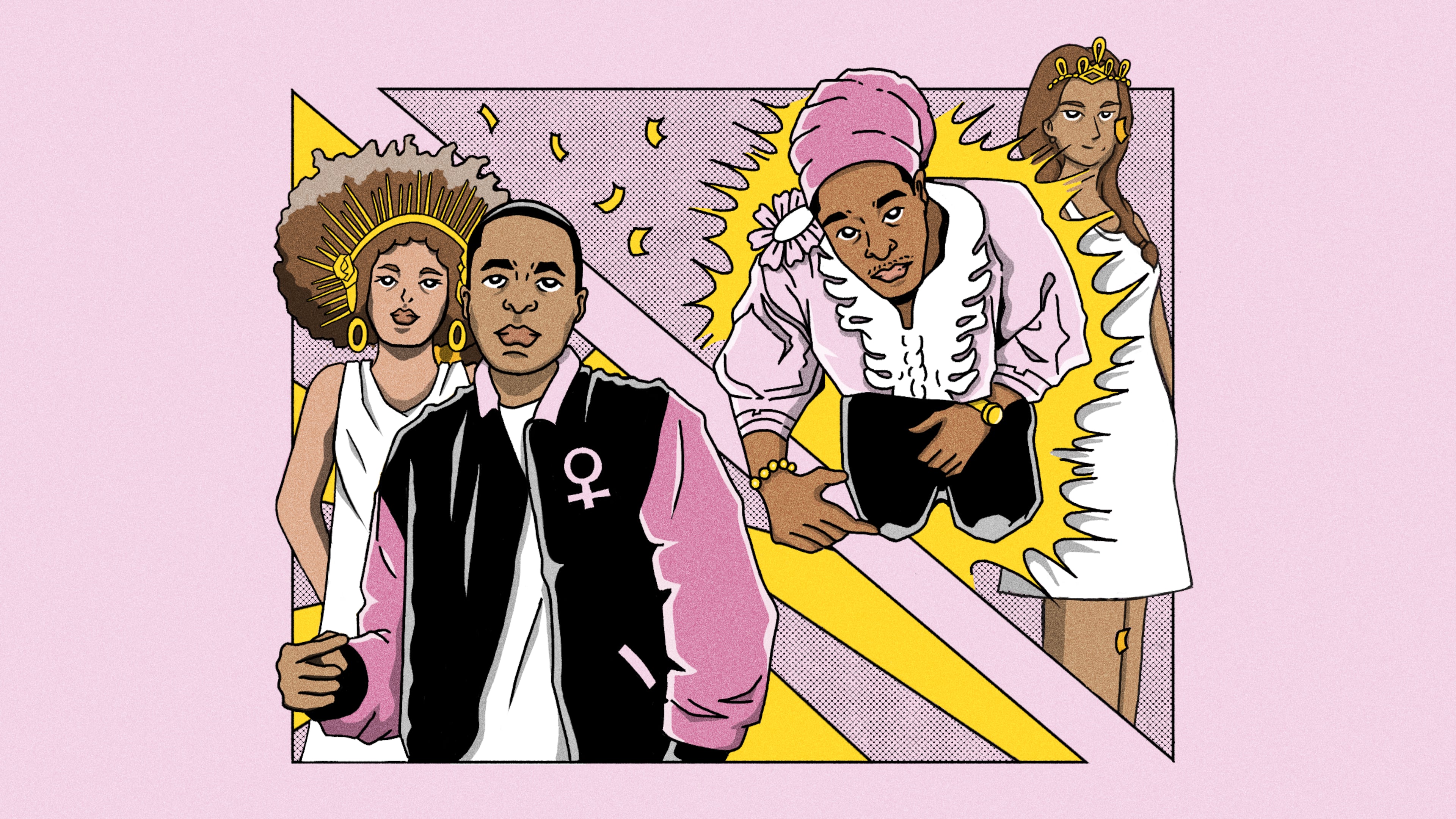

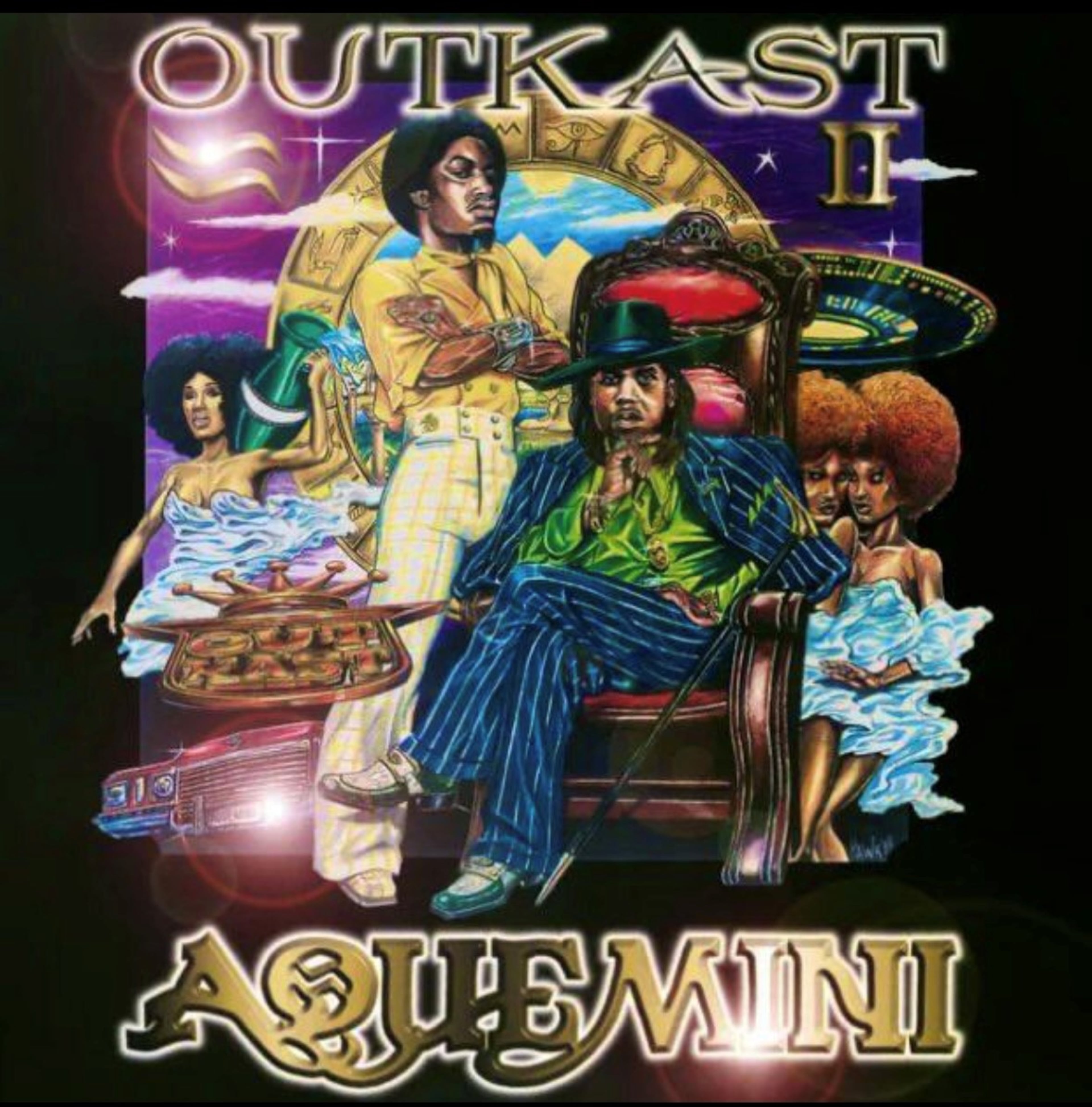

That attention to balance extended to everything they touched. Outkast designed worlds and albums. Even their CD art played a role in the story.

“Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik,” “ATLiens,” “Aquemini” and “Stankonia” trace a visual evolution of the feminine from body to cosmos to muse to liberation. Before you hit play, the discs themselves were already speaking in a feminine code.

On “Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik,” the woman is full-bodied and bold, drawn in thick, earthy lines that echo revolutionary, funk-era album art. She’s decoration and foundation. Rocking afro-puffs, two on each side, she embodies the softness of the red clay soil that raised them. She’s Mother South itself.

By “ATLiens,” she has ascended. Her body dissolves into silhouette and stardust with the feminine reimagined as a cosmic force guiding them through their spiritual and sonic Afrofuturist expansions.

“Aquemini” makes that energy abstract: Swirling colors and layered shapes hint at the female form, but now she’s integrated into the design; no longer pictured, she’s part of the pattern.

And by “Stankonia," one of their most politically embedded albums, she’s fire itself. Her hair twisted into Bantu knots with a unicorn horn. Her curved body painted in psychedelic flame. Blue lashes and black eyes dare whoever is holding the CD to meet her gaze. It’s a surreal, fiery embodiment of the feminine. To me, it reads creative combustion, transformation and liberation all at once. You hear it in “Slum Beautiful,” in lines like “Baby, my darlin, you make me lose composure.”

Across the albums, the visuals said what the songs already knew. That the feminine wasn’t something to possess or perform. Outkast understood that rhythm long before it was fashionable to talk about gender balance or emotional intelligence in hip-hop.

My theory is that rappers gained confidence sing-rapping about women after André showed them how. You can hear harbingers of it in the layered harmonies of “SpottieOttieDopaliscious,” where live horns breathe like lungs, or in the organ runs of “Liberation,” a gospel-infused meditation that centers Erykah Badu and CeeLo Green in spiritual dialogue.

The Love Below

Benjamin and Patton are 50-year-old men now. Patton is a granddad. The women who raised Outkast — the mothers, aunties, baby’s mommas, baby’s mommas mommas — are fundamental to who they became.

They made space for self-correction, which is straight out of the Southern woman’s playbook. That playbook, grounded in the moral and aesthetic traditions of Black Southern womanhood, insists on love, balance and accountability from everyone.

It’s no coincidence that the birthplace of the Dungeon Family’s sound was in the home basement of Rico Wade’s mother. The Dungeon was the studio, but it was also the womb that incubated the sounds of soul Organized Noize Productions created for Outkast. Those stories would tell us about being young, gifted and Black, surviving in Atlanta in the ’80s and ’90s.

Outkast’s induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame is a milestone for hip-hop. But it’s a “see? I told you so” to anyone in that 1995 Source Awards audience who brushed ‘Kast off as delulu.

The feminine frequency Outkast channels has always been partly mythic, partly maternal, partly muse. Taken together, those discs form a theology of womanhood: embodied, elevated, integrated and liberated. The music carried the message, but the art confirmed it.

It affirms how imagination can remake the world when filtered through the South’s creative intelligence. Southern women, women in general, are essential to that logic.