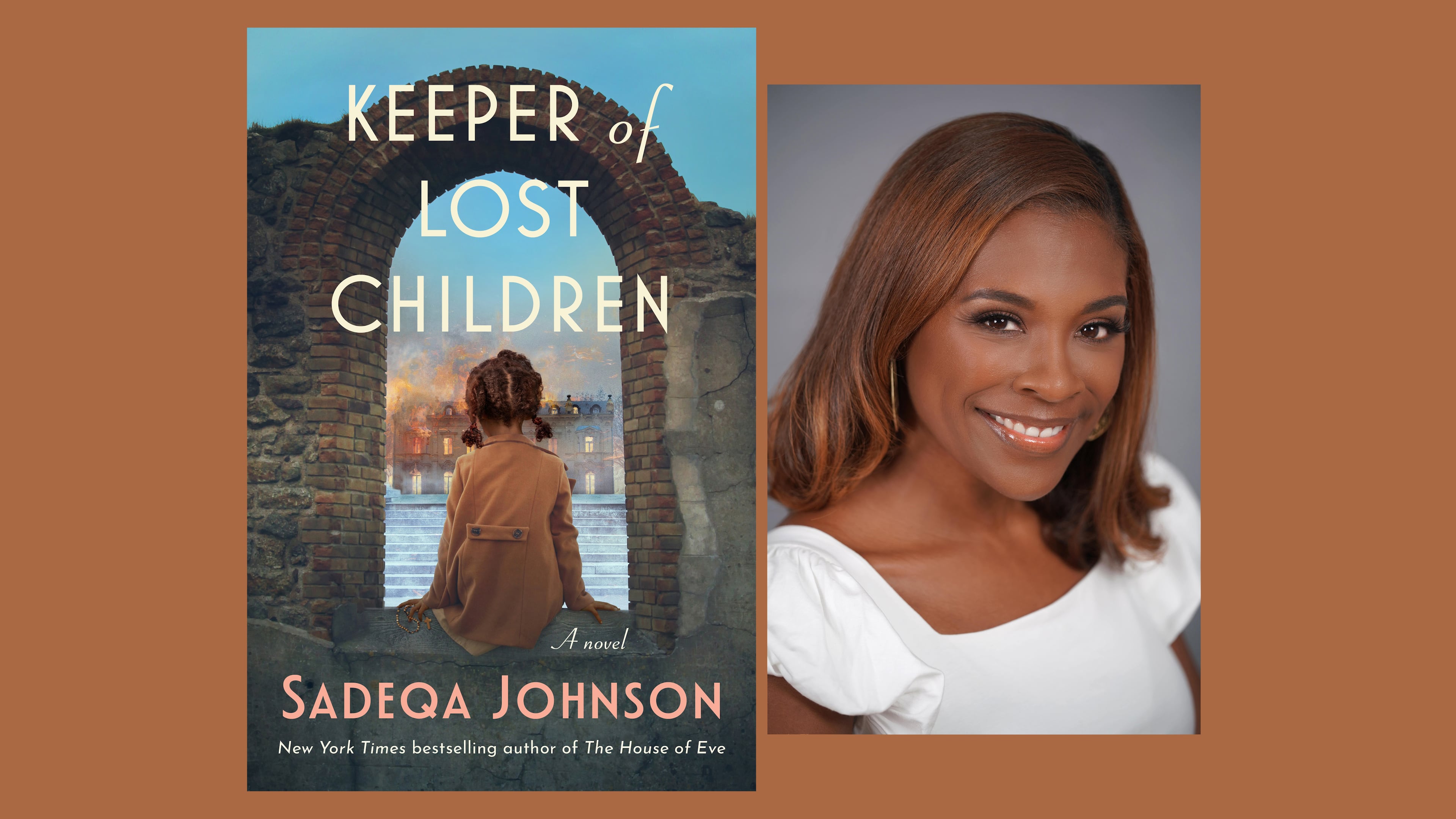

Author Sadeqa Johnson wants to resurrect forgotten Black history

New York Times bestselling author Sadeqa Johnson is making a stop in Atlanta to discuss her latest historical fiction novel and how the city’s civil rights history influenced a major element of the story.

On Feb. 20 at the Margaret Mitchell House in Midtown, Johnson will go into detail about “Keeper of Lost Children” with investor and reality TV personality Tanya Sam.

“So much of (Black) history is buried or just kept from us,” Johnson said, adding that rediscovering hidden history gives her motivation as a fiction writer. “Why are these stories of these unsung heroes, these Black women, not being amplified?”

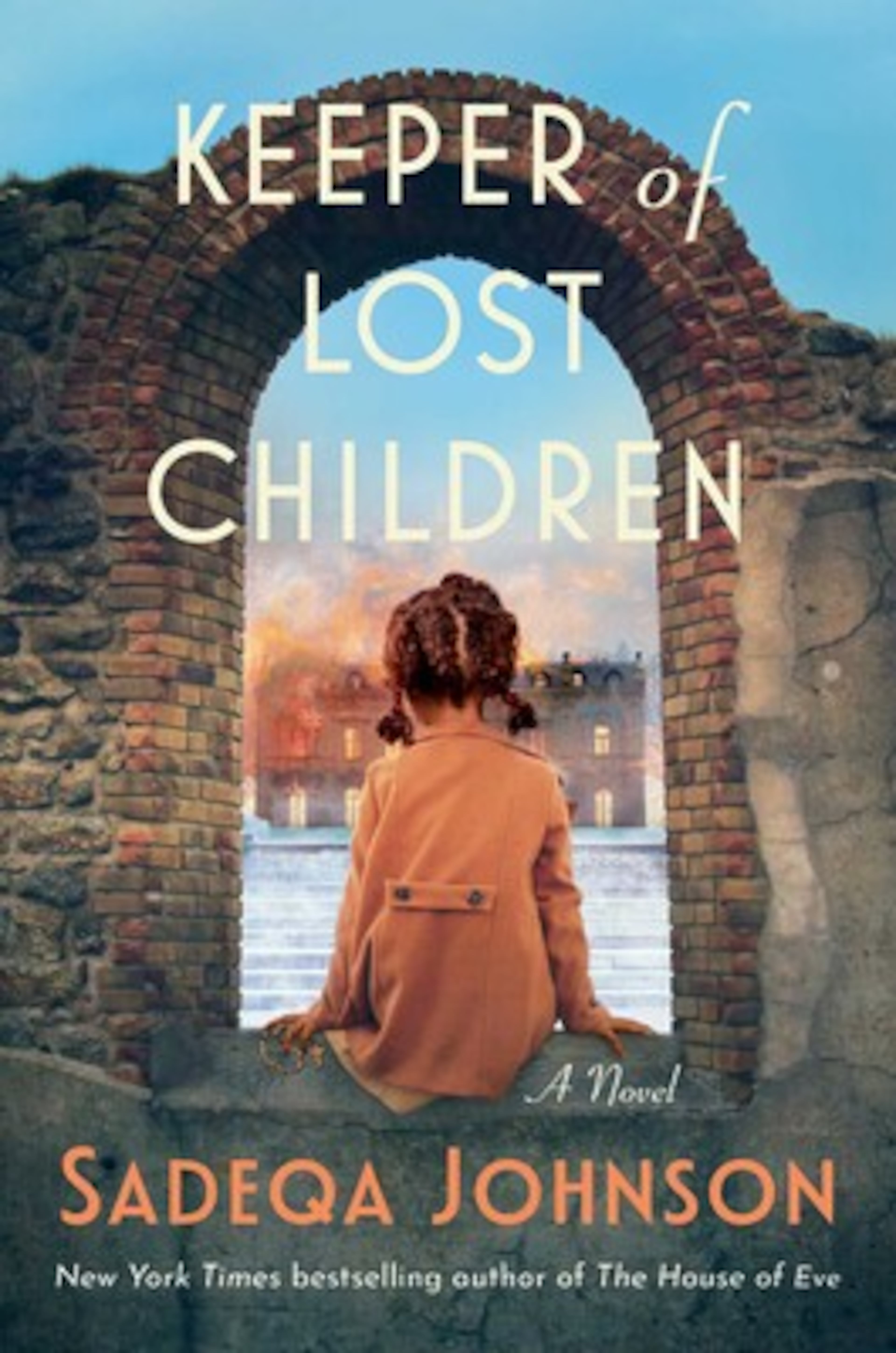

“Keeper of Lost Children” takes place from 1948 to 1964, mainly between Maryland, Philadelphia and Germany. Three narratives during that span of time are woven together to tell a larger story about Black American soldiers stationed in post-World War II Germany, the relationships they had with German women and the livelihoods of the multiracial children — or mischlingskinder — that resulted from those unions.

The Maryland story centers around Sophia Clark, one of the first Black students to integrate a prestigious, all-white boarding school. Sophia never felt like she belonged within her family at home. Being one of the few Black students in her highly esteemed academic institution doesn’t alleviate her feelings of isolation. As a high school sophomore, Sophia attempts to reckon with her placement among white peers, Black students who come from prominent families and then within herself as she searches for identity.

Sophia’s experience was inspired by the Atlanta-area Westminster Schools in the 1960s. Multiple racial incidents documented at the school were portrayed in “Keeper of Lost Children,” including students participating in an Old South dance where they dressed in antebellum and Confederate attire. The book also dives into Westminster’s reported “slave auction.”

Johnson, author of “House of Eve,” believes some of this Black American history has been hidden by families keeping secrets.

“Our history of the whole country — not just for Black people — but the whole country goes back to slavery,” Johnson explained. “We had to whisper. We had codes. We could only say certain things we didn’t want to be found out. I think that sort of has built into our family history where we’re still holding some of those secrets.”

She rooted history gatekeeping to Black people, essentially, being embarrassed by their origin in the U.S.

“The fact that we were enslaved and we came here was shameful. And I think we still carry a lot of that into our everyday dialogue within our families,” Johnson explained.

Ozzie Philips is a young Black man from Philadelphia who travels to Germany with the Army. He has a bright future and looks forward to enriching his professional endeavors. However, racism overseas stalls his progress, and he searches for other ways to cope — particularly through alcohol.

“Alcoholism was really important for me to write about in the story because I think it’s one of those things that is very prevalent in our community. And it’s almost like it’s normalized,” Johnson explained. “You’re numbing the pain … until it becomes something that you lose control of.”

The novel also focuses on classism, self-sabotage, identity crises, parenting and guardianship within the Black community.

Finally, Ethel Gathers is the wife of a Black man who has been stationed in Germany. She battles infertility issues of her own, taking it upon herself to volunteer with a local orphanage. She helps place multiracial children in forever homes with Black families — both abroad and in the U.S. and free of racial ostracization.

Ethel is based on the true story of Mabel Grammer, whom Johnson said she found by accident while researching for another book.

“(Grammer) discovered these mixed-race children and decided that something needed to be done,” Johnson said. “Mabel Grammer was a hero, and not many people know about her.”

Johnson noted that much of the history behind “Keeper of Lost Children” is not known because Black women’s voices have been silenced. Despite the work of Grammer being featured in multiple Black magazines and newspapers, some of which she wrote, the history of the adoption program is not well-known.

“I’m only a few generations removed. I’m the lucky one. I get to do all of these things because of what my ancestors have done,” she said. “I definitely believe that stories choose me and that I have to be in the right space, in the right place in order for the story to find me.”

Johnson says her “ancestral” duty as a historical fiction writer is to keep these stories alive, adding that she leaves “breadcrumbs” to inspire readers to continue researching about change makers of whom she writes.

“When I pulled these (Black) women from our history, it’s me honoring them. It’s me giving them a voice because maybe their voices weren’t as loud as we needed to hear them, but I know that I wouldn’t be able to do this without them,” she said.

“I am because they were.”