How Carl Joe Williams illustrates B.B. King’s genius for children

Carl Joe Williams remembers when he realized art’s power to educate communities and celebrate cultural identities.

As a student at Atlanta College of Art in the early 1990s (now Savannah College of Art and Design’s Midtown campus), he visited the High Museum of Art to view a quilt by Faith Ringgold in 1991.

Williams wanted to create like Ringgold and mixed media artist Romare Beardon. He spotted “Tar Beach,” a children’s book about a Black girl who could fly over Harlem, New York, in the gift shop and was surprised Ringgold wrote and illustrated it.

“My mind was completely blown because I was a fan of her contemporary work. It just let me know I could make art and use children’s books for my own artistic practice,” Williams said.

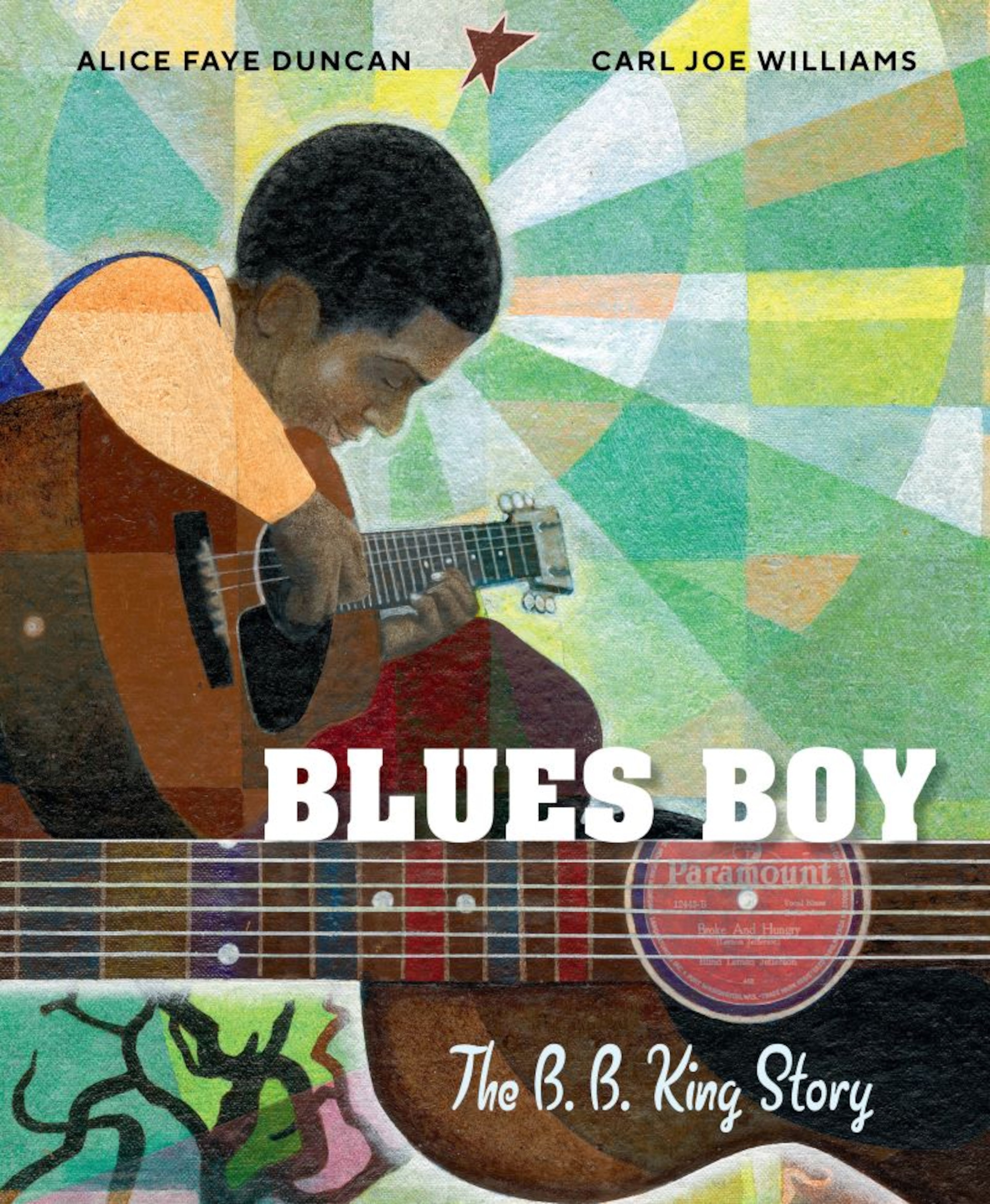

Today, he’s the illustrator of “Blues Boy: The B.B. King Story,” a children’s storybook written by Alice Faye Duncan about the life of the Mississippi-born, Grammy-winning blues singer and guitarist. The book, released Jan. 27, features collage paintings that depict King overcoming racism and poverty to become a famous musician and superstar.

It includes song lyrics, a timeline, biography, suggested recordings, literature and tourist destinations.

Williams had creative latitude for the illustrations. “I got to do my own thing and didn’t get a whole lot of direction. It wasn’t my writing, but I didn’t really care because Alice was so easy to talk to, and I enjoy collaborating with people on a particular vision,” he said.

Williams moved to Atlanta from New Orleans in 1988. He considered Chicago but decided to pursue an art career close to his hometown. “It was a Black city, and still in the South. I hadn’t really been anywhere except Houston,” he said.

Four years later, Williams took part in his first group exhibition curated by Eddie Granderson, who later became City of Atlanta’s public art program manager. The show featured work by Radcliffe Bailey and Kara Walker.

Williams, who lived in Midtown, moved into his first art studio at the intersection of Auburn and Piedmont Avenues the following year.

He said the neighborhood sparked his creativity. “I was the guy who’d be upstairs painting while everyone was outside having a good time at the Royal Peacock, walk down to the store, buy single cigarettes, sit on the corner, drink a cup of coffee, and go back to the studio,” he said.

Williams supported himself working as a security guard, server at the Peachtree Club, and substitute teaching for Atlanta Public Schools. He spent free time perfecting his craft.

“I was a struggling artist, but I had my sketchbook with me, working on my art, and applying for possible projects,” he said.

In 1996, Williams designed two sculptures outside Sweet Auburn Curb Market for the Summer Olympics. It was his first public art project.

Williams’ uncle encouraged him to apply. It motivated him to take pride in himself.

“I had no public art experience at all, but he told me ‘You could do this.’ We worked out that proposal, turned it in, and it made me confident in my ability,” he said.

Williams also created murals at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport and Washington Park Tennis Center.

Williams went back to New Orleans but returned to Atlanta in 2005 after Hurricane Katrina displaced residents.

Williams said that return to Atlanta motivated him to pursue art full-time. “I got a lot more serious about building an art career,” he said.

Williams illustrated his first children’s book, “Mardi Gras Almost Didn’t Come This Year,” by Kathy Z. Price. It’s a story about a family recovering after Hurricane Katrina. “You have to know the culture, and my goal was to bring that story to life in the most realistic way that I could,” he said.

Williams is currently working on “Under Water,” a children’s book about the history of Lake Lanier, and reuniting with Duncan on another book about Black music history.

Williams hopes to inspire youth to seek creative possibilities through children’s literature.

“Working on children’s books is a continuum of me giving back to young people, teaching them what art can be and look like without actually being in the classroom,” he said.