Gamechangers: ‘90s Black Atlanta Braves stars changed perceptions

When you walk into Walter’s Clothing in downtown Atlanta, it’s hard to not confuse it with the Atlanta Braves Clubhouse store at Truist Park. Actually, they may have a better selection. You’ll find a spectrum of Braves fitted caps that can match hundreds of shoes on the wall. You can even walk out with a Braves Starter jacket in a color that would make even Ronald Acuña Jr. envious. The store has solidified itself as a spot to get Braves gear all year, for fans and casuals.

It wasn’t always like this.

“When I got to Walter’s in 1985, man, the Braves sucked,” said longtime employee Patrick Morrison. Morrison grew up in College Park, played baseball for the former Lakeshore High School and cheered for the Braves, not necessarily because of the team, but because of his love of the sport. He, like many others, weren’t rushing to Walter’s or any store for that matter, to find Braves gear to wear proudly.

“They had some real bad teams,” he recalls.

If local fans knew this, surely opposing players took notice as well.

“I remember coming into town as a St. Louis Cardinals player and I couldn’t believe the bumper stickers on the cars,” said retired MLB player and former Braves third baseman Terry Pendleton. “They would say ‘Go Braves! and take the Falcons with you!’ And I’m like, are you kidding me? These are Atlanta people with this on their cars? What is happening here?”

The answer to that question is, after getting the city’s hopes up winning the National League’s West division title in 1982, the Braves spiraled into eight years of mediocrity.

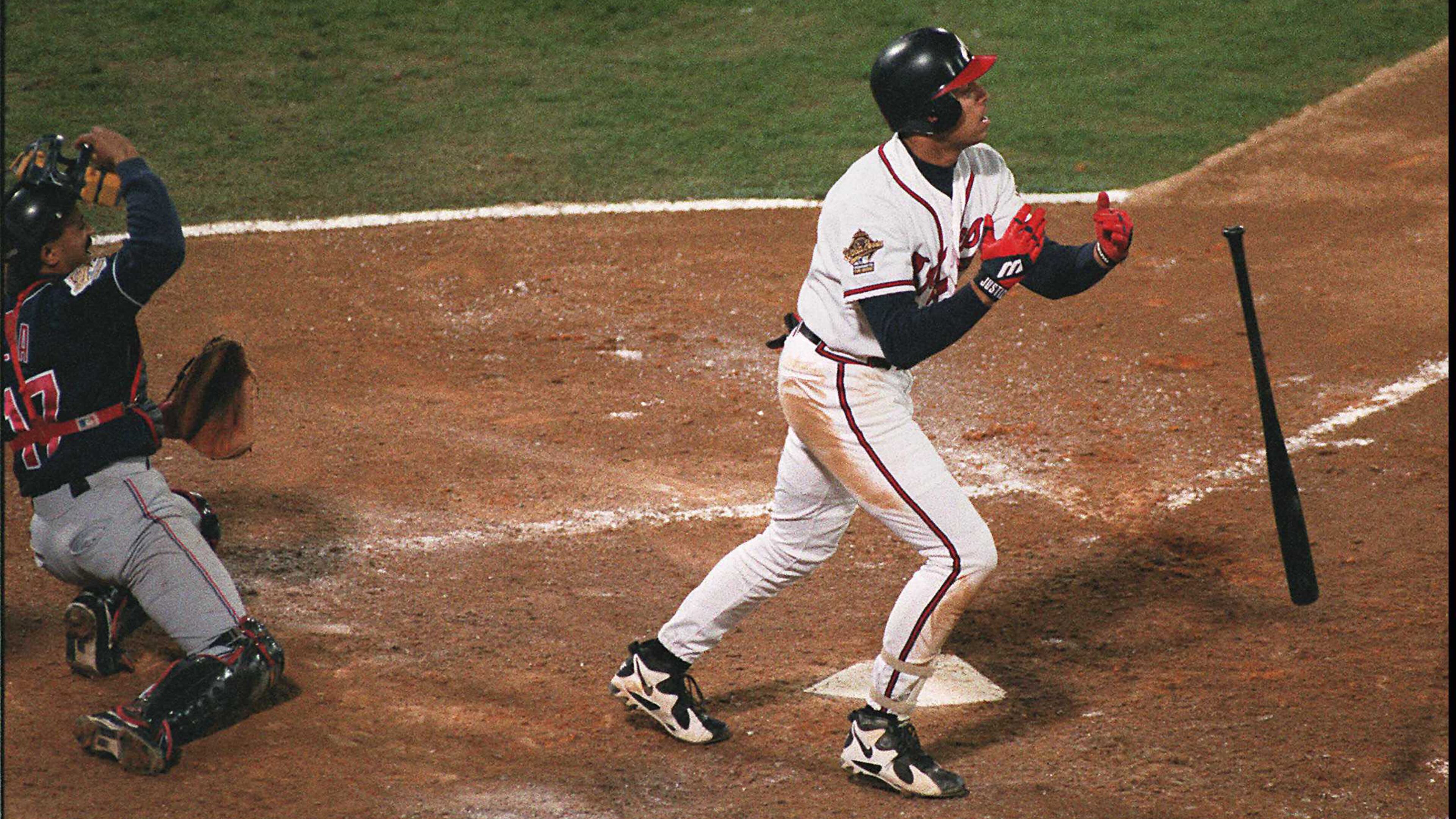

The 1990 season brought drastic changes that gave a glimpse of the future. Then Braves general manager Bobby Cox fired manager Russ Nixon midseason and took over the team himself just weeks after drafting future Braves legend Chipper Jones. Two-time league MVP Dale Murphy was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies and replaced with newcomer David Justice who went on to win the NL Rookie of the Year Award that same season, essentially making him the first potential Black star of the team since Hank Aaron retired in 1976.

But, Justice was also one of many.

The Braves’ early ’90s rosters prominently featured All-Star level Black players including Justice, Pendleton, Ron Gant, Fred McGriff and Marquis Grissom as well as talented fan favorites like Deion Sanders, Brian Hunter and Otis Nixon. Today, Black players represent just over 6% of those on 2025 opening day rosters (compared to about 18% in the 1990s). With Atlanta hosting this year’s edition of the All-Star Game, former Black players and fans find themselves reminiscing over those ‘90s Braves heyday.

‘Like an HBCU team’

With Justice already earning a ROY award, he brought additional star power to the city when he married ’90s “it girl,” actress Halle Berry. Pendleton brought veteran savvy to the clubhouse, winning the National League MVP in 1991. Gant became a fixture in the community and returned to be a color commentator and television anchor on three different Atlanta stations after retiring.

Sanders became the first Atlanta athlete to have his own signature Nike shoe. And Nixon? Well, he had kids from Bankhead to Buckhead scaling walls trying to emulate his legendary Spider-Man catch against the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1992. McGriff and Grissom brought offense that finally got the Braves over top and won a World Series in 1995.

“Honestly, that really wasn’t something that shocked you, because growing up in Cincinnati, I was used to playing baseball with a lot of brothers,” Justice said. “But now looking back, and then you look at the state of the game today, that’s amazing how many brothers we actually had.”

“It was awesome, especially going into the lunchroom after batting practice, and there’s 10 brothers in there watching BET,” said former Braves pitcher Marvin Freeman who played for the team from 1990 to 1993.

Before joining the big leagues Freeman played collegiately at Jackson State University in Mississippi.

“We’re in there eating chicken, telling jokes and talking about each other’s mamas. It was almost like an HBCU team. The chemistry was just off the chain. To have that many Black dudes on one team was something that I had never even thought about experiencing.”

“I’ll go on record all day long and say that our group, we were the ones that changed the face of the Atlanta Braves, worldwide” said Justice.

Gamechangers

The face of the city itself was changing right along with them.

This core group played at a time when Atlanta was experiencing an influx of Black folks relocating to the city, as it grew out of its Civil Rights “city too busy to hate” nickname and into its “Black mecca” distinction. A 1998 Census Bureau survey found that between 1990 and 1996, more than 150,000 Black Americans moved to Atlanta, a city known with a reputation for upward mobility, consecutive Black mayors and Freaknik.

“We had a bunch of young dudes that you could vibe with and we played the game the right way too,” adds Justice. “We played hard, we had fun, and we were good. So I feel like we represented the city very well.”

The Braves were also rising at a time when Atlanta’s music scene was doing the same. LaFace, SoSo Def and Rowdy Records were each redefining how the world saw and heard Atlanta as they pumped out artists like TLC, Outkast, Kris Kross, Xscape and Monica. Over time, it became a norm to see artist like these wearing Braves hats and jerseys, transforming it from sport merchandise to cultural calling cards.

“When you saw Big Boi, Andre 3000 and all of them wearing Braves jerseys, that’s what got the people to buy them, not just the Braves team itself,” said Morrison, who designs much of the exclusive Braves gear sold at Walter’s. “People really just want to represent Atlanta. Some of the rappers and people who wear Braves stuff ain’t never been to a game.”

“It was great playing here and seeing the start of the whole hip-hop thing,” said Justice, mentioning that he often hung out at spots like Club 112, Rupert’s and Frozen Paradise. He adds he never got to experience Freaknik because for some reason, the Braves would always have away games that time of year. “It was a lot going on in the early ’90s and we were in our 20s, just having a great time in a freaking great city.”

If players in their mid-20s were having a ball, imagine the memories they were creating for the kids watching them.

“It wasn’t just that we had Black players, we had brothers that was coming in with some swag,” said Marwon Palmer, 45 an Atlanta native who grew up in the Summerhill neighborhood where Braves played their games at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium between 1966 and 1996 and then Turner Field from 1996 to 2016.

Palmer worked concessions at Fulton County Stadium. He has fond childhood memories of being able to hear home runs and Tomahawk Chop chants from his front porch. He met Justice’s ex-wife Berry at the old Kentucky Fried Chicken across the street from the stadium. “They had everybody wanting to wear the Braves fitted caps and Starter jackets. Then when Deion [Sanders] got his own Nike shoe, that just took it all to another level.”

The players felt it, too.

“We could see the vibe changing,” said Pendleton, noting that he met fans who were traveling to games from neighboring states like Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, the Carolinas and Florida, which didn’t have an MLB team at the time.

“No matter where they came from, they recognized us as Black players and what we were doing to kind of change the culture,” he said. “The young Black kids wanted to be baseball players instead of football and basketball players. And that was encouraging in itself.”

Beyond the diamond

One of those kids was Ben Githieya, 47, who grew up in the former Capitol Homes housing projects, a short walk from the old Fulton County Stadium.

“In the ’80s when Dale Murphy was here, we just played one hop with a tennis ball,” said Githieya, describing the game as one where the batter hits the ball and tries to clear as many bases as possible before the ball is caught. “When the Braves started winning, you saw a lot more folks getting real baseballs, real bats and getting on the field playing the game for real.”

While the players on the field were earning millions to play, the Braves winning also boosted the local economy, legally and not so legally.

The general understanding of the area was that people who lived in Summerhill made money charging people to park in their neighborhood, while Mechanicsville sold barbecue plates. Their neighbors up the street in Capitol Homes held down the ticket scalping hustle.

“More people probably bought Braves tickets in the ’90s from Capitol Homes than they did directly from the Braves,” laughs Palmer.

“The Braves winning changed the trajectory of the whole hood,” said Githieya who recalls friends of his who were selling drugs, finding out they could make less riskier money scalping tickets.

With Fulton County Stadium being sandwiched between Summerhill, Mechanicsville and Capitol Homes and being right off the Downtown Connector, it opened a market for anyone with an idea to get paid.

“We would be at the stadium all the time and people would just give you tickets they weren’t using. Instead of going to the game, we would sell them and we learned you could make money off this. Or, you could buy 100 cheap tickets for $1 and sell them for $20, that was better than dope money.”

Speaking of numbers, baseball is game obsessed with stats. Pundits willingly call the Braves of that era “the team of the ’90s,” winning the division title every year that decade, appearing in seven National League Championship series and playing in five World Series.

Critics will always point to the disappointment of them only winning one world championship in that stretch. Statistically, yes, the Braves should have hoisted the Commissioner’s Trophy more often. But culturally, the Braves and their Black players were always seen as champions in the city.

“Thirty years later, I can walk in a supermarket or just be walking somewhere down the street, and somebody has a Braves hat on,” Pendleton said. “I don’t say a word to them. I just smile, because I believe in my heart, I had a little bit of something to do with that.”