How Atlanta remains a higher education mecca for Black students

In 1989, following graduation from Atlanta’s Frederick Douglass High School, Stacy Renee Robinson-Collier dreamed of becoming a student at Clark Atlanta University.

Her older sister attended Spelman College, and she wanted that Black college experience.

However, her father forbade it, fearing the idea of his daughter taking the train to class. She enrolled at Oxford College of Emory University. In many ways, it was a world away from Clark Atlanta. It was 38 miles east of Atlanta and had about 35 Black students.

“I felt like a fish out of water,” Robinson-Collier said. “I needed that Black experience.”

She dropped out after a year, started a family, and built a career in media.

In 2020, 31 years after graduating high school, she earned a degree in broadcast journalism — and, she says, enjoyed that full “Black experience” — from Georgia State University.

Several members of Robinson-Collier’s family and most of her close friends had attended GSU, where they studied, played sports, socialized, joined Greek organizations, and, most importantly, graduated.

“I know it’s not an HBCU, but to us, it is,” said Robinson-Collier, a special education coordinator in Atlanta Public Schools. “We’re in there.”

Robinson-Collier continued her new family legacy this month by helping to move her son, Richard Collier III, into his GSU campus apartment.

“Georgia State was his first — and only — choice,” she said.

Atlanta’s claim as a Black mecca for higher education is not just historical — it is active and growing.

For more than a century, the city’s HBCUs have cultivated Black intellectual, cultural, and civic leadership. Now, institutions like Georgia State, with nearly half of its 50,000 students identifying as African American, demonstrate that large-scale equity and opportunity in higher education are possible.

Kennesaw State University, about a half-hour drive from Atlanta’s city limits, had close to 15,000 Black students last year. Several of Atlanta’s HBCUs reported receiving a record number of applications for this school year.

Together, these schools make Atlanta a place where Black futures are not only imagined but actively built.

“Atlanta continues to provide a rich ecosystem of culture, business, and politics that complements the academic mission,” said Clarissa Myrick-Harris White, senior professor of Africana studies at Morehouse College. “Students don’t just earn degrees; they become part of a broader movement — socially, politically, and economically — that reinforces Atlanta’s status as a Black Mecca for higher education.”

A legacy with numbers behind it

The phrase “Black Mecca” has clung to Atlanta since the 1970s, describing its rare mix of Black political power, cultural influence and economic strength. But the city’s higher education record shows that the title isn’t just symbolic — it’s measurable.

A 2013 Metro Atlanta Chamber report showed Atlanta ranked first among the 100 largest U.S. metro areas for growth in African American full-time college enrollment, number one for the increase in African American college graduates and second in total number of African Americans in college.

And the growth hasn’t stopped.

Census-based estimates from City-Data Forum show that in 2020, southwest Atlanta had close to 20,000 Black residents with bachelor’s degrees — second only to “Uptown DC” among major Black communities.

In 2023, Atlanta’s universities awarded 34,535 degrees, according to Data USA. More than one-third of those degrees, 10,596, went to Black students, making them the largest racial cohort of degree recipients.

From Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens, a Georgia Tech alum, to entrepreneur Pinky Cole, a Clark Atlanta grad, to DeKalb County Sheriff Melody Maddox, who was a member of Morris Brown College’s famed “Bubbling Brown Sugar” dance team, Atlanta’s colleges and universities have shaped the careers of many Black people who lead organizations and businesses that keep the city going — and help make its case as the Black Mecca.

“At one time, that title may have belonged to Washington, D.C., with Howard University,” Clark Atlanta University President George T. French Jr. said. “But this is the Black Mecca for higher education — full stop.”

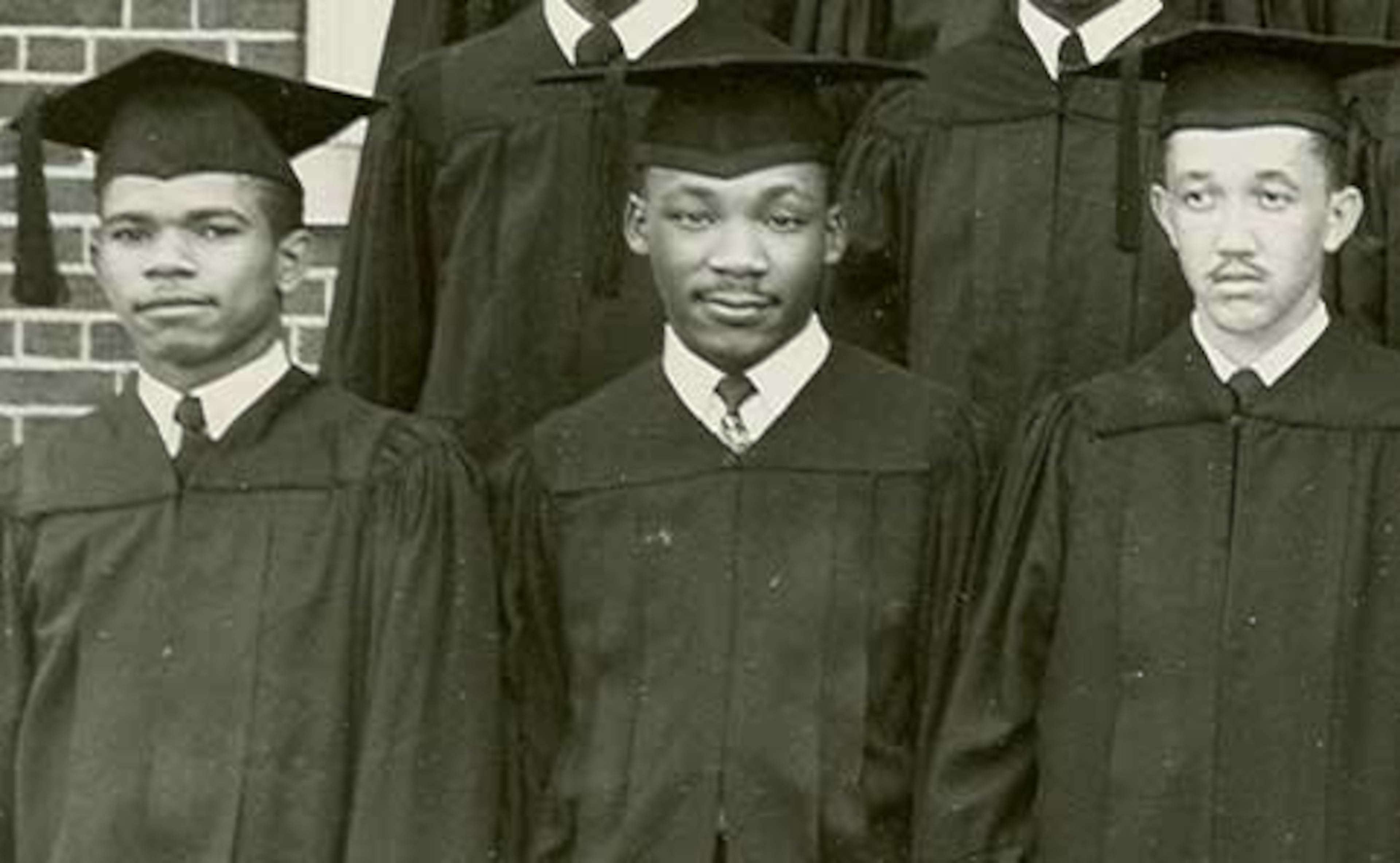

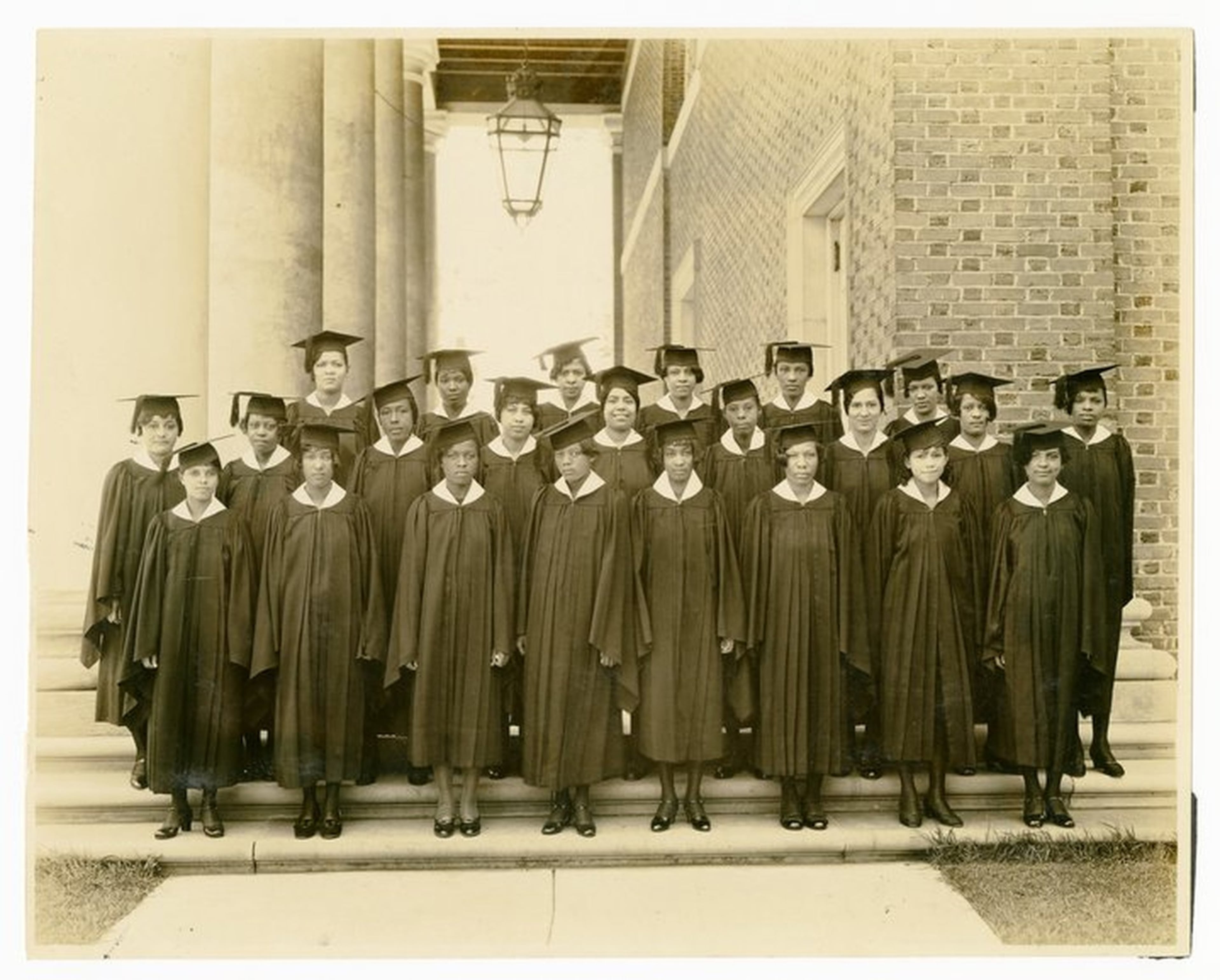

The Historic Heart: The Atlanta University Center

If Atlanta is the Black Mecca for higher education, the Atlanta University Center Consortium is its temple. The AUC — composed of Morehouse College, Spelman College, Clark Atlanta University, Morehouse School of Medicine, the Interdenominational Theological Center and the resurgent Morris Brown College — is the oldest and largest cluster of historically Black colleges and universities in the world.

Founded between 1865 and 1881 — Atlanta University in 1865, Morehouse in 1867, Clark College in 1869 and Morris Brown and Spelman in 1881 — the AUC schools formed a network dedicated to teaching fundamentals, training leaders, and preparing African Americans to navigate political and economic power.

Morehouse’s Myrick-Harris White said the legacy is rooted in Reconstruction, when the city became a destination for African Americans from rural Georgia seeking to rebuild their lives, reunite families and build community.

“After the Civil War, the city attracted a critical mass of African Americans seeking education, community and economic opportunity,” Myrick-Harris White said. “The combination of intentional community-building, churches and educational institutions created a concentration of educated African Americans that was rare.”

Today, the AUC enrolls over 9,000 mostly Black students, a living legacy that stretches from Reconstruction-era classrooms to 21st-century boardrooms, laboratories, and film sets.

Michelle S. Hite, director of the Ethel Waddell Githii Honors Program at Spelman, points to the collaborative strength of the AUC.

“We understand the collective value of the AUC. We see each other. What one of us does, we all do. We rise together,” Hite said.

For Max Grace Brown, an incoming Spelman freshman psychology major from Raleigh, N.C., she wanted to be part of that rising tide.

Brown, who was born in Atlanta, said the Spelman community, combined with the city’s rich Black culture, sealed the deal.

She watched her mother, Vickie Suggs-Jones, struggle to hold back tears as parents were asked to leave Sisters Chapel following the school’s emotional Parting Ceremony, where the 600 new students are formally bid farewell.

“There’s something powerful about being in a city where so many other young Black people are working toward the same goals,” Brown said. “It’s not just about getting a degree — it’s about being part of a network for life. Atlanta felt right.”

Recruitment, retention and the CAU approach

Across the AUC at Clark Atlanta, as freshmen were moving into their dorms, Cheri Peters, vice president for enrollment management and student life, roared through campus on a golf cart with Provost Charlene Gilbert riding shotgun.

Gilbert was helping students move in, while Peters was trying to keep things moving.

CAU, which is in the middle of a $250 million capital campaign, received nearly 50,000 applications for this year’s class of 2029. Of those, 19,000 were accepted and about 1,215 are expected to arrive on campus.

“When you have 50,000 people knocking at your door and only 1,200 spaces — that’s a blessing, a burden and a responsibility,” Gilbert said, adding that she is still looking for 15 more beds. “We take it seriously, but that’s the power of what’s going on at Clark Atlanta University right now. We’re doing everything to make it work.”

French said after the 2023 U.S. Supreme Court decision striking down race-conscious affirmative action in college admissions CAU also saw an increase in middle-class Black families choosing the Atlanta school over Ivy League options like Harvard or Yale.

The average grade-point average of incoming freshmen has jumped since 2019 from 2.8 to 3.71. While the percentage of Georgia students at CAU has risen from 20% to 30%. Other than Georgia, the state with the highest number of students is California.

The new powerhouse: Georgia State University

While the AUC protects Atlanta’s historic crown, Georgia State University has become the city’s new engine of scale for Black student success.

For nine years straight, GSU has awarded more bachelor’s degrees to African Americans than any other nonprofit institution in the country, according to the National Center for Educational Statistics.

In 2024, according to the University System of Georgia, 22,348 of GSU’s 52,423 students — over 42% — were Black.

Comparatively, only 7.5% and 6.4% of students at the University of Georgia and Georgia Tech, were listed as Black.

Statewide, GSU educates 24% of all Black students attending public universities.

In 2012, it became the first U.S. institution to award more than 2,000 bachelor’s degrees to African Americans in a single year, and it hasn’t slowed since.

In 2023, two years after M. Brian Blake became the school’s first Black president, GSU conferred 2,810 degrees to African American students, outpacing the number awarded to white students (2,229).

Just as important, GSU has narrowed racial graduation rate gaps to nearly zero. Since 2015, the African American graduation rate has risen 29 points, now standing at 53%.

That change didn’t happen by chance, university officials say. It came from deliberate interventions: predictive analytics to flag at-risk students early, proactive academic advising, and microgrants to prevent dropouts over financial emergencies.

Making students feel valued

Black higher education in Atlanta extends beyond the AUC and Georgia State.

At Clayton State University, 62% of its 6,100 students are Black, while at Kennesaw State 28% of its 48,000 students are Black.

Atlanta Metropolitan State College, though not an HBCU, enrolls about 1,600 students — roughly 90% Black — with an average age of 26.

Founded in 1974 as a junior college it attracts learners from across Georgia and internationally, including the Bahamas, Gambia, Germany, Kenya, Nigeria and Senegal.

“Our students see the campus as a safe space where past failures are not counted against them,” said President Ingrid Thompson-Sellers. “Our staff and faculty care deeply, empowering students despite challenges or insecurities about higher education. Students feel valued — they are not numbers.”

The college offers certificates, associate degrees, and six bachelor’s programs, with elementary and special education launching in spring 2026. Tuition is $107 per credit hour — about $1,284 per semester for 12 credits — with classes available on campus, online, or in hybrid formats.

Affordability is an important element for many Black students. The state’s HOPE and Zell Miller scholarships help pay some or most of the tuition for Georgia high school graduates who attend in-state public universities.

Why they stay

From his boyhood home in Windsor, Connecticut, just 43 miles north of Yale, Marcus Blackwell’s Atlanta roots still ran deep, even though he had no intention of going to school here. Summer vacations included trips to his grandmother, Krispy Kreme and Morehouse, his dad’s alma mater.

Blackwell initially resisted following his father’s path, wanting to forge his own.

But after a leadership pre-college program at Morehouse and experiencing what he called “unmatched Black culture,” he changed course.

“I’d never experienced the freedom of being my full Black self. Up north, our northern swag — do-rags, fitted caps — often came with negative perceptions and my dad, being a Morehouse man and corporate guy, didn’t let me lean into that style,” Blackwell said. “But times are different now. In Atlanta, this is who we are.”

After earning a math degree in 2009, Blackwell stayed in Atlanta — a pattern reflected in a 2018 study showing 30.7% of metro-area Black adults hold at least a bachelor’s, versus 21.8% nationwide.

He worked at GE while pursuing music as a director and pianist at local churches, and recently left to launch “Make Music Count,” an app teaching math through popular piano songs.

“The village that I’ve built here because of Morehouse makes Atlanta that type of Black Mecca, where I can do anything,” said Blackwell, who has settled into Atlanta’s Westside with his wife, a Spelman graduate, and two children. “I don’t feel like I would have gotten that in any city other than Atlanta. I’ve been set up for success here and there wasn’t any need for me to go anywhere else.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: This article has been updated to include the Interdenominational Theological Center in the list of Atlanta’s HBCUs.

ABOUT THIS SERIES

“Atlanta: America’s Black Mecca?” is an original content series from UATL that explores that question with data-driven, thoughtful reporting that prioritizes the voices of locals and transplants who call this city home. These stories will appear in the paper, UATL.com and AJC.com each month through January 2026.

Got a Black mecca story to tell? We want to hear about your experiences. Hit us up at uatl@ajc.com.

Become a member of UATL for more stories like this in our free newsletter and other membership benefits.

Follow UATL on Facebook, on X, TikTok and Instagram.