Founders of Black History Month bring annual conference to Atlanta

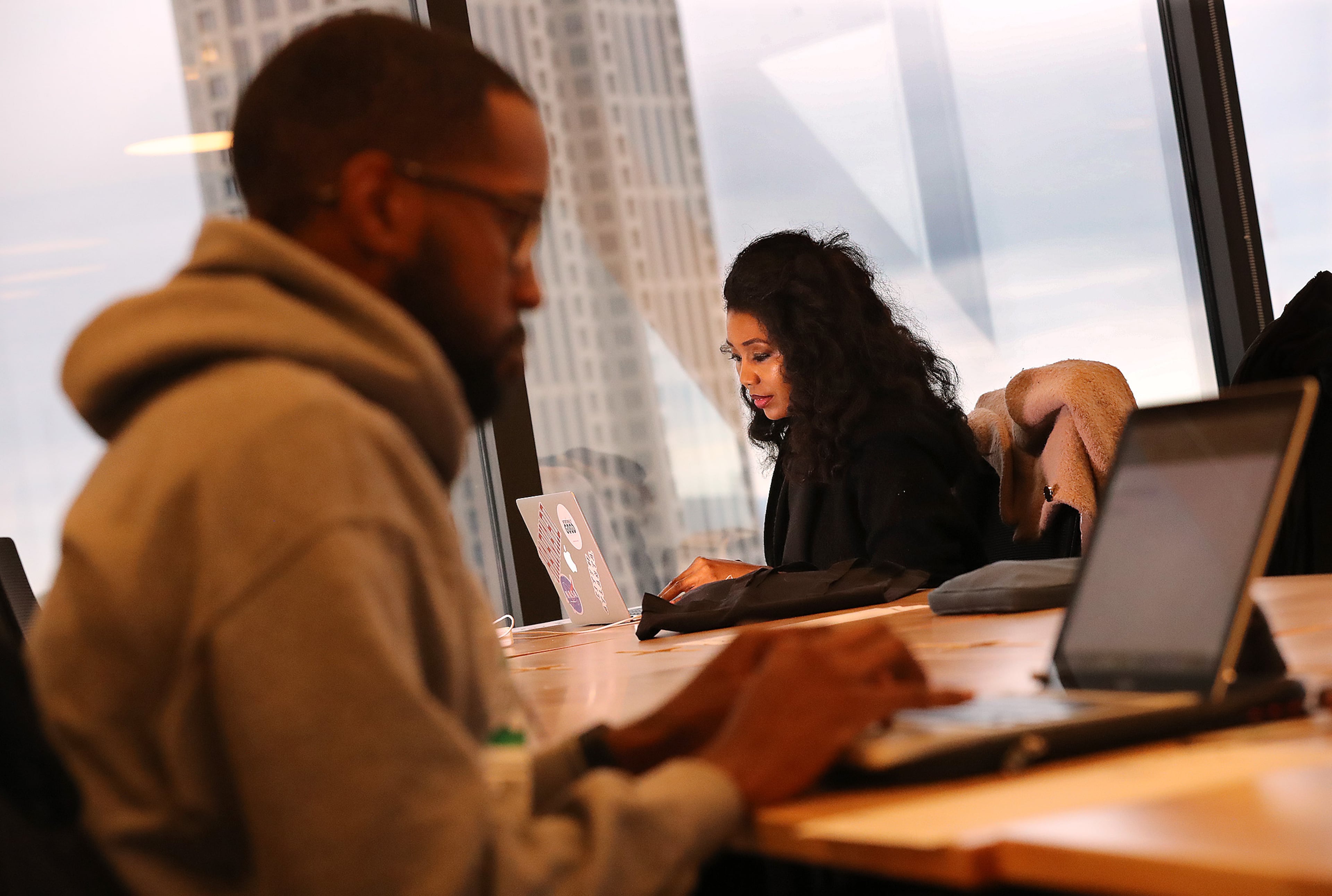

Work has always been at the center of the Black experience in America — from the stolen labor of enslavement to the organizing struggles of today.

That history, along with its modern echoes, takes center stage when the Association for the Study of African American Life and History — an organization founded more than 100 years ago by Carter G. Woodson — brings its annual convention to Atlanta on Wednesday.

The conference’s theme, “African Americans and Labor,” will explore the ways work — whether free or unfree, skilled or unskilled, vocational or voluntary — has shaped Black life across centuries.

Organizers say the programming will not only celebrate the contributions of Black workers but also challenge the nation to reflect on how labor continues to define the Black past, present and future.

That reflection comes as Black Americans face mounting pressures, both economic and cultural. According to seasonally adjusted data released last week by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the unemployment rate for Black workers rose to 7.5% in August, the highest since October 2021. By comparison, the overall unemployment rate stands at 4.3% and, for white Americans, 3.7%.

In addition, federal layoffs, budget cuts, and rollbacks of diversity, equity and inclusion programs have contributed to more than 300,000 Black women exiting the workforce. Black women now face an unemployment rate of 6.3%, also the highest level since October 2021.

“That’s exactly why we’re convening — to discuss these numbers in the context of historical patterns and understand how they’re affecting people today. Behind those numbers are countless stories,” said Zebulon Miletsky, associate professor of Africana Studies at Stony Brook University and chair of ASALH’s marketing and communications committee.

At the same time, cultural battles over the teaching of race and history continue to escalate. Earlier this month, the National Park Service was ordered to remove exhibits related to slavery, citing a March executive order from President Donald Trump directing the Interior Department to strip away content that “disparages Americans past or living.”

In Georgia, that meant removing “Scourged Back” from Fort Pulaski National Monument, near Savannah.

The devastating photograph, taken in 1863 of a formerly enslaved man named Peter, shows his scarred and beaten back — remnants of his days in bondage. Abolitionists used the image as a key piece of evidence against the horrors of slavery.

Against this backdrop, ASALH leaders say their gathering will serve as both a scholarly exchange and a public forum on the meaning of work in Black life.

Sharita Jacobs-Thompson, a full-time professor at Prince George’s Community College, said the removal of the photograph is not just the erasure of a single image but part of a broader attempt to reshape the story of Black history.

“I conduct tours at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, and I’ve seen firsthand the attempts to reshape how Black history is presented. It’s sad but predictable, echoing patterns seen in the late 1800s and early 1900s when scholars at major institutions framed slavery as civilizing,” Jacobs-Thompson said. “But those efforts won’t stop the deep connection African Americans have to their history — genealogy and family history matter. Organizations like ASALH are critical in filling that gap, exactly what Woodson envisioned: correcting the record and producing new scholarship.”

ASALH was founded in 1915 as the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History by Carter G. Woodson, often called the “Father of Black History.” The organization’s goal was to preserve and promote the study of African American life, history and culture.

Under Woodson’s leadership, the ASALH created key research and publication outlets for Black scholars, including the “Journal of Negro History” (1916) and the “Negro History Bulletin” (1937).

In 1926, Woodson launched Negro History Week, timed to coincide with the birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. That observance was later expanded to the full month of February in 1976. Today, ASALH continues to shape Black History Month by providing annual themes that guide scholars, historians, organizations, and media outlets in their teaching and coverage.

Today, most of the 5,000 members of the organization are “curators of African American history, teachers, archivists, bibliophiles, master teachers and community builders,” Miletsky said.

The Atlanta convention will feature a mix of academic sessions, public programming and cultural events.

Headliners include Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Edda Fields-Black; author and activist Ibram X. Kendi; historians Peniel Joseph, Maurice Hobson, Stephanie Evans and Joe Trotter Jr.; and Chris Smalls, the Amazon Labor Union leader whose organizing effort made history in 2022.

Other prominent voices expected include Ambassador Andrew Young and Andrea Young, Pastor Jamal Bryant, former Atlanta Mayor Bill Campbell, State Rep. Omari Crawford and Michael Julian Bond.

Organizers plan to make many sessions free and open to the public. That programming includes panels, film festival screenings, poster sessions, vendor exhibits and the Friday evening author book signing.

Panel discussions will tackle issues ranging from threats to preserving African American history in the nation’s parks, to the current state of Black radicalism, to the scholarship of labor historian Joe William Trotter Jr.

Ticketed luncheons will highlight Smalls and feature a discussion of Carter G. Woodson’s legacy and his ties to the fraternity Omega Psi Phi.

The convention will also include practical workshops designed to help teachers, librarians, and community leaders establish Freedom Schools and expand access to Black history education in local communities.