National Center for Civil and Human Rights to reopen after $57M expansion

When the National Center for Civil and Human Rights reopens on Nov. 8, it will do so almost exactly a year after the 2024 election — a timing that feels oddly fitting in a country still grappling with its past.

In the intervening months, cultural institutions nationwide — most notably the Smithsonian — have come under attack from critics, including the president, who argue that museums downplay American exceptionalism and should soften or even eliminate exhibits that highlight the nation’s darker chapters.

For the National Center for Civil and Human Rights, reopening after months of construction carries weight far beyond new galleries and classrooms. It is a statement about the role of museums as storytellers, even in a polarized time.

“In this country, there’s a movement to tell only a triumphalist story about America. That’s really propaganda,” said Jill Savitt, the center’s CEO since 2019.

She came to Atlanta from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, where she led its international genocide prevention program.

“The real story — our whole story — is so much more powerful,” Savitt added. “Every country has painful chapters. America is no different. But here, we tend to deny those chapters or fight over them, instead of embracing them as part of a shared American family story.”

Savitt said when the center reopens after its $57 million expansion, it will continue to tell Atlanta’s and the nation’s stories about civil and human rights. The goal, she said, is to elevate the center from a local attraction to a national cultural institution.

“No one could have planned for us to open a year to the day after the presidential election, but it feels meaningful. In this polarized time, where we can’t agree on much, gathering people around a shared view of our American family can only be positive,” Savitt said. “There’s never been a more important time in my lifetime to tell this truth. Yes, there have been other tough periods — John Lewis was beaten, Martin Luther King Jr. and Medgar Evers were murdered, the Depression, enslavement. But this is our moment.”

Located in the heart of the downtown tourism district and surrounded by the World of Coca-Cola, the Georgia Aquarium, Centennial Olympic Park and the College Football Hall of Fame, the center has been closed to the public since January.

So on a media tour Wednesday, Savitt and Kama Pierce, the center’s chief program officer, were more than eager to lead reporters through the noisy, dust-tinged halls of the downtown museum in the final stages of construction.

Hard hats and safety jackets in place, the two moved between the bare floors and walls of the new wings, their eyes tracing the space where future exhibits will hang.

One wall awaits the rare Thornton Dial painting, while another room tells the story of racial violence as told through the eyes and voice of Ida B. Wells.

“Until I see the exhibits in place — and the media — I won’t be able to breathe,” said Pierce, who oversees exhibits, programming and education at the center. “But I’m excited for what we’ve built. I’m excited about the way we’ve told the history.”

Pierce’s anticipation reflects the painstaking work behind the scenes, but for Savitt, the blank walls represent something even larger — a lesson in history and the choices that have shaped it.

“What do I see? I see an answer to a big question that people have in our country right now: ‘What’s going to happen?’” Savitt said. “I see that history is not inevitable. I see the blank walls right now, but these walls are going to tell you how it’s gone down in the past, and how people got together and made plans and were brave.”

Since opening in 2014, the $75 million, 42,000-square-foot center’s stated mission has been to inspire visitors “to tap their own power to change the world around them.”

In 2024, the center marked its 10th anniversary with plans for an ambitious $38 million expansion to add two new wings and significantly increase its footprint. But the pandemic, supply chain disruptions and rising labor costs pushed the price tag to $56.6 million.

The center ultimately raised $58 million through grants and donations from organizations including the Wilbur and Hilda Glenn Family Foundation, the James M. Cox Foundation, the Coca-Cola Foundation, the Mellon Foundation, AEC Trust, Home Depot and UPS.

Savitt said the additional funds will cover “wish-list” items, such as new office space.

The center is growing by 50%. The project includes a three-story west wing named for Arthur M. Blank, who contributed $15 million to the center’s capital campaign in 2022, and a one-story east wing named for former Atlanta Mayor Shirley Franklin.

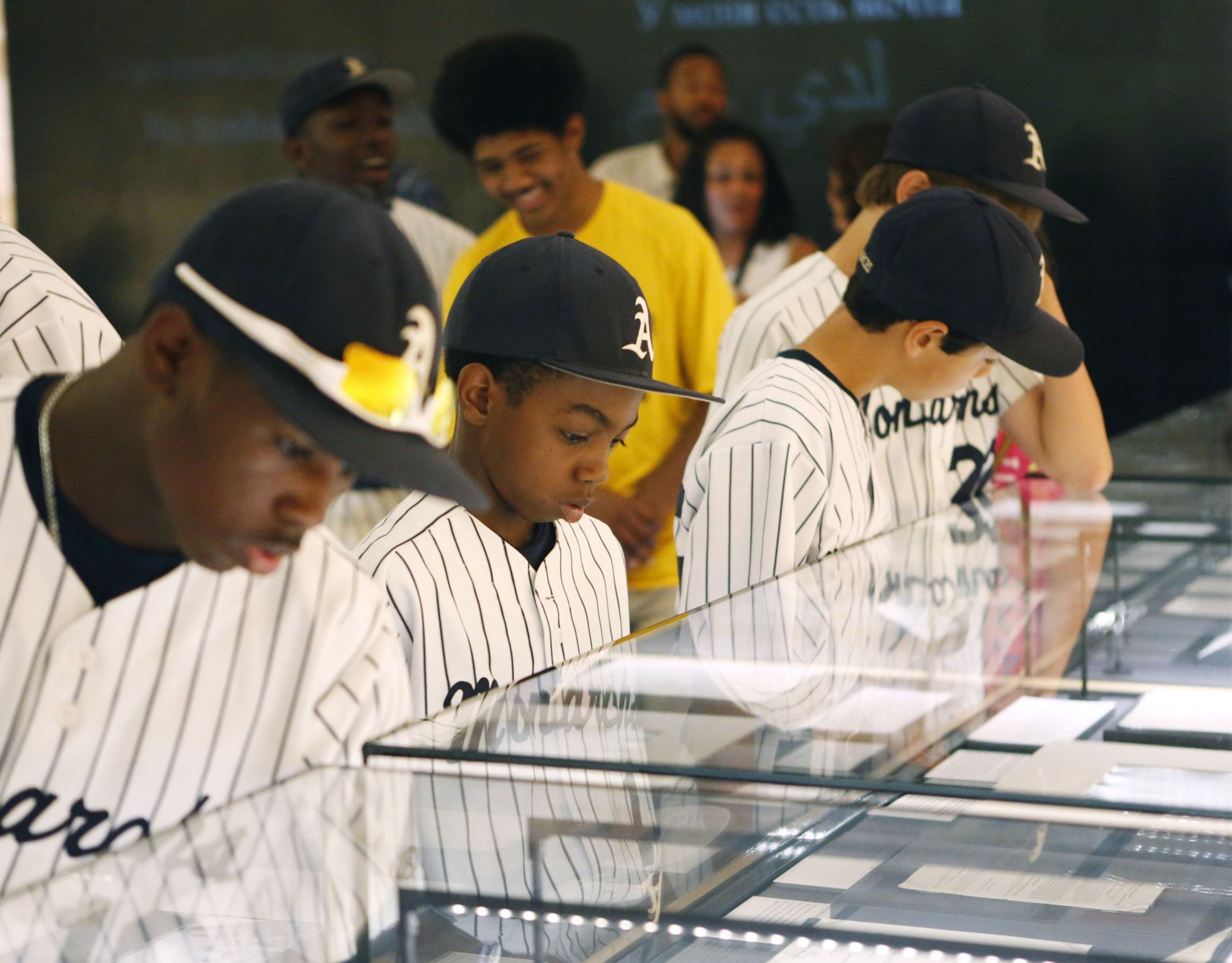

The Arthur M. Blank Inspiration Hall will feature a first-floor cafe and new galleries devoted to racial violence, Reconstruction and a dedicated space for families and children.

The Shirley Clarke Franklin Pavilion will include classrooms and flexible spaces for large-scale dinners, performances and conferences. Its roof will serve as a ticketing hub and outdoor event space.

Franklin, as mayor in 2006, helped secure the $32 million purchase of the Morehouse College Martin Luther King Jr. Collection — a cornerstone of the center’s holdings — that prevented King’s papers from being auctioned and scattered.

The King Papers will be relocated from the basement of the Franklin Pavilion to the main floor in the space formerly occupied by the bookstore.

Previously, visitors had to seek out the collection, but the redesigned center now makes seeing the King Papers “nonnegotiable,” Savitt said.

Bernice King, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s youngest daughter, will serve as the first “guest curator” for the reimagined King Papers. Savitt said her involvement, along with rotating exhibits and other curators, will keep the center dynamic and engaging.

The familiar exhibit hall has been expanded and reconfigured. An “Atlanta Alcove” will tell the city’s civil and human rights history. At least three reflective spaces, complete with sofas and tissues, will offer visitors a moment to pause and absorb.

The “Lunch Counter Sit-In Simulation” — the center’s most emotionally charged exhibit — will double in size to nine seats, immersing visitors in the tension and courage of activists confronting racism firsthand.

On Nov. 4, the center will host a ribbon cutting, where Blank and Franklin will inaugurate their wings.

When the center opens to the public on Nov. 8, all exhibits will be ready except for “Broken Promises,” which will open in December and focus on the Reconstruction era, and the Family Gallery, which will launch next spring.

Savitt sees the Family Gallery as crucial to drawing families and younger visitors. It will be an interactive, hands-on way to teach civil and human rights lessons in a city that attracts millions of tourists but previously offered few experiences tailored for children.

Before the pandemic, the center drew roughly 200,000 visitors annually. Numbers fell to about 150,000 afterward.

“When we reopen, we’d love to get back up to that 200,000, which is really what we need in terms of revenue,” Savitt said. “That’s the sustainable number. To survive as an institution, we need to bring people in.”