Abby Phillip reclaims Jesse Jackson’s forgotten political legacy

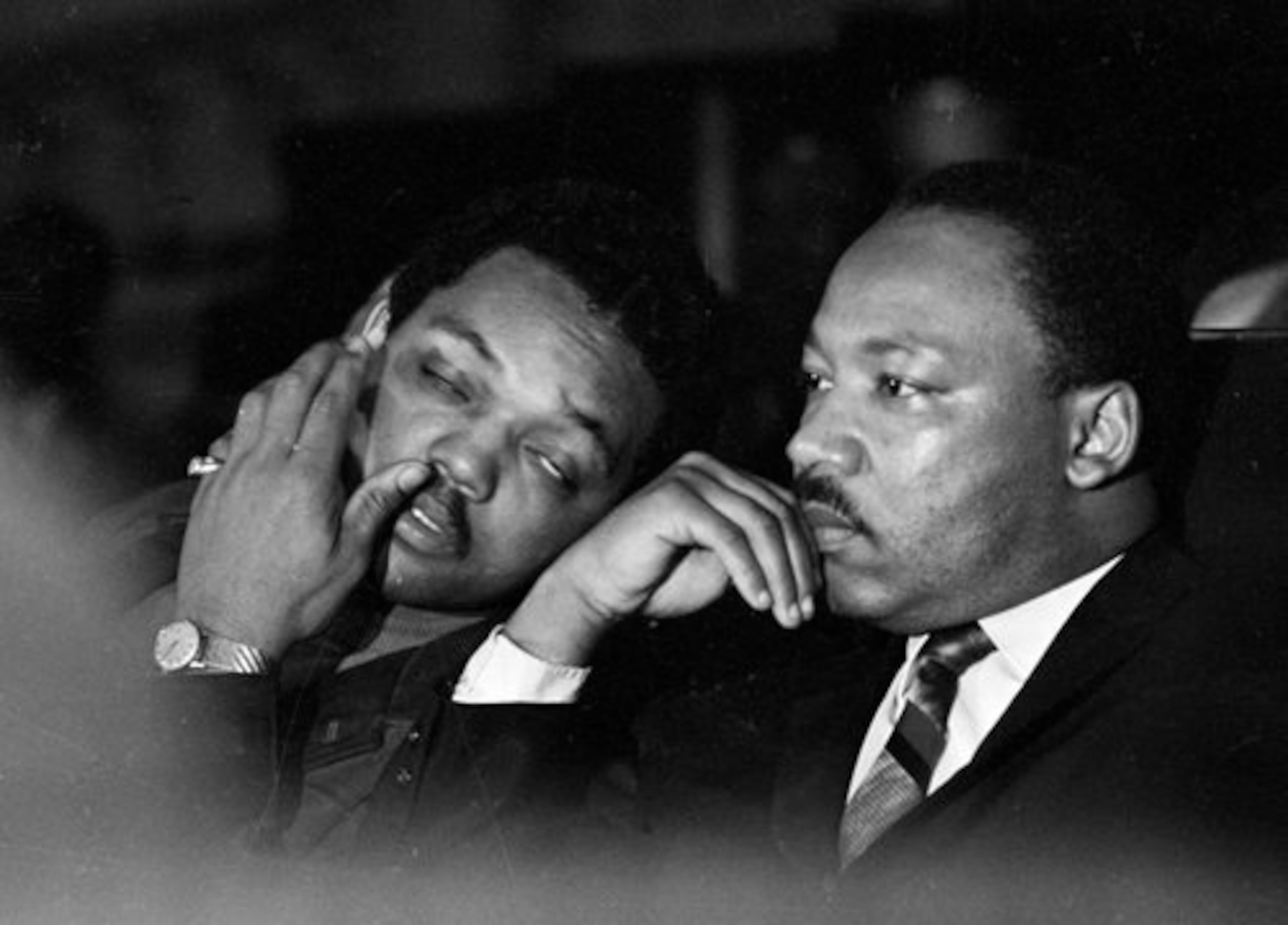

For decades, Jesse Jackson has embodied the power of protest — a steadfast presence in America’s long fight for civil rights, marching alongside the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Andrew Young, Hosea Williams and John Lewis.

What history often forgets is the other stage where he made history: the presidential campaigns of the 1980s that redrew the map of Democratic politics.

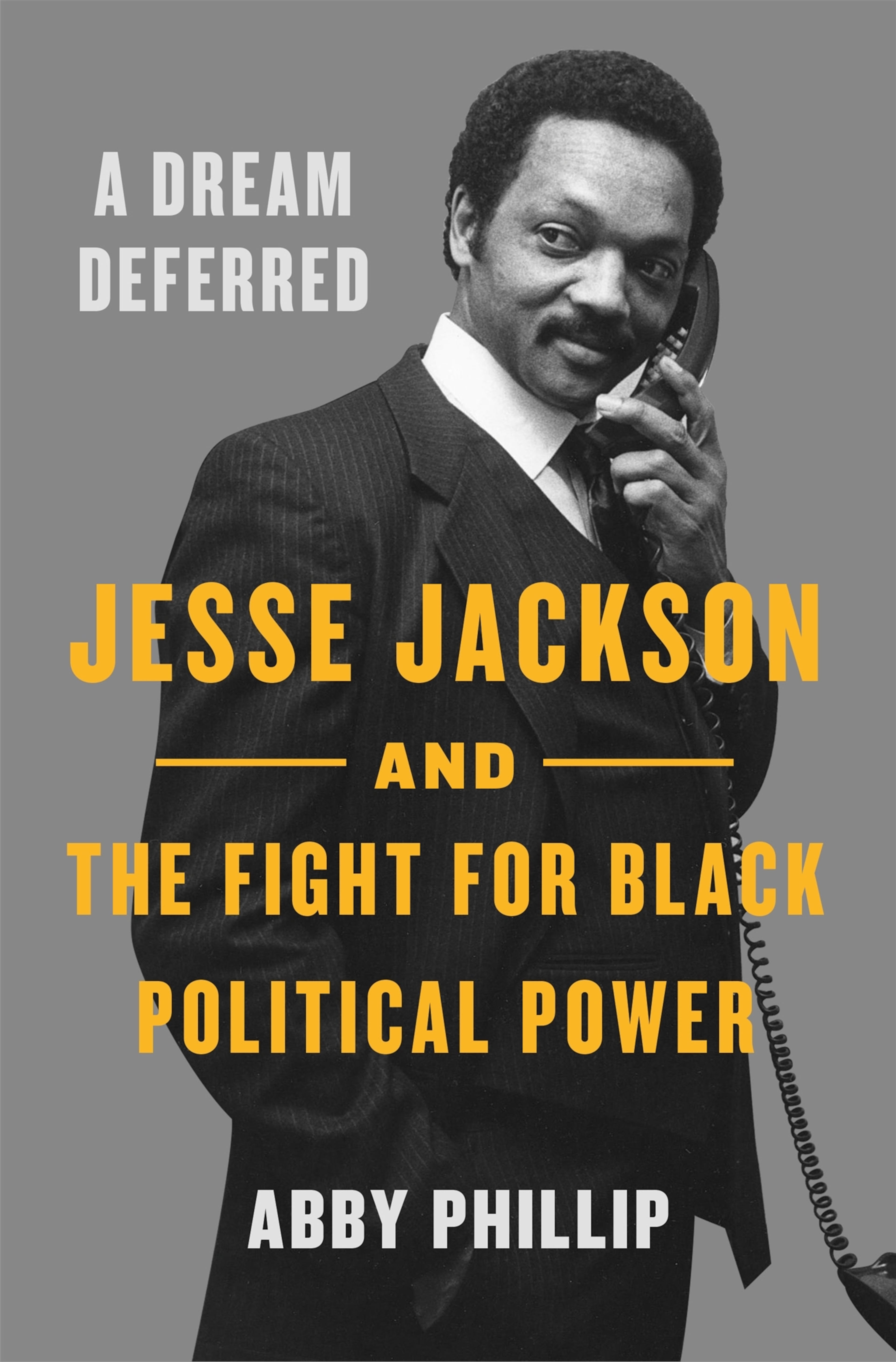

In her new book, “A Dream Deferred: Jesse Jackson and the Fight for Black Political Power,” CNN’s Abby Phillip reclaims that story, restoring Jackson’s political legacy — one that helped shape the modern Democratic blueprint — to its rightful place in the national record.

That gap in understanding, Phillip argues, reflects how history so often flattens complexity.

“People know about his civil rights activism, but they don’t know as much about his political chapter. Or why it matters,” Phillip said. “And if you experienced it in the 1980s, I don’t know that it was as clear then as it is now just how much his campaigns shaped the framework for how the Democratic Party operates today.”

Phillip’s “A Dream Deferred” borrows its title from Langston Hughes’s 1951 poem “Harlem,” which asked whether a deferred dream “dries up like a raisin in the sun” — or “explodes.”

The book tells the story of how a boy who grew up not knowing his father became a movement preacher, a civil rights activist, and ultimately, a presidential contender.

Through vivid reporting and historical insight, Phillip traces how Jackson’s years under King, his leadership of Operation Breadbasket in Chicago, and his deep roots in the Black South laid the foundation for one of the most ambitious political experiments in modern American history.

She charts Jackson’s evolution from protest to politics, showing how the lessons of the Civil Rights Movement shaped his presidential runs in 1984 and 1988.

Those campaigns, Phillip writes, fused moral authority with political ambition, drawing together working people, students and Black voters into a broad coalition that redefined what the Democratic Party could be — a blueprint still visible from Barack Obama to Kamala Harris to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

“Jesse stood in the midst of history and made some too,” said Ambassador Andrew Young, a longtime ally. “This book is an important reflection on the evolution of Black political power and Jesse’s role in it. This is a story that needs to be told.”

Phillip will sit down with Young on Wednesday, Nov. 5, at the Atlanta History Center for a conversation about her book.

Phillip, who hosts “NewsNight with Abby Phillip” on CNN, wasn’t even alive when Jackson was filling college arenas and rewiring the Democratic Party, demonstrating how Black political power could be both consolidated and expanded.

In fact, she was born just three weeks after Jackson ended his second and final presidential campaign in 1988.

But she was drawn to Jackson’s story after covering the 2016 and 2020 presidential campaigns, which saw the rise of figures like Bernie Sanders, a fiery populist who channeled economic frustration into a national movement that challenged the Democratic establishment.

“People kept asking, ‘Where did this come from?’” she said. “And a lot of folks said to me, ‘Jesse Jackson. Jesse Jackson is where this came from.’”

That realization became the spark for her book. The parallels between Sanders’s populist surge and Jackson’s multiracial, working-class coalition were impossible to ignore.

“That message of economic populism — the outsider candidate running against the establishment, galvanizing young people on college campuses, filling stadiums — all of that was reminiscent of Jesse Jackson,” Phillip said. “It led me to wonder how much we really understand about what Reverend Jackson contributed to politics.”

Before Obama’s historic victory in 2008 and Harris’s near miss in 2024, there was Jackson, a brash, magnetic preacher-turned-politician who believed the pulpit and the podium were one and the same.

In 1984, he was initially dismissed as a fringe Democratic candidate but ended up winning five primaries and caucuses, including Louisiana, the District of Columbia and South Carolina.

Fueled by chants of “Run, Jesse, Run!” and later “Win, Jesse, Win!,” he finished third in the 1984 Democratic primary to Walter Mondale and second in 1988 to Michael Dukakis. Neither man went on to win the presidency.

Phillip writes that in reshaping the Democratic Party, Jackson redefined who the party represented by bringing millions of new voters, especially Black Southerners, into the process.

He campaigned in small towns where Black people weren’t always welcome and stood with Southerners who had once been on the other side of the civil rights struggle.

“Jackson didn’t just inspire Black Americans to believe a Black man could be president,” Phillip said. “He literally changed the rules of the Democratic Party, making it possible for an outsider, nonestablishment candidate to win a primary — even after losing the big states.”

The early caricature of Jackson as a publicity-seeking activist, Phillip argues, “completely misses the real work and the intellectual depth that went into his campaigns.”

“He had an intellect, flexibility and charisma that were rare in politics,” Phillip said. “Even today, many politicians can’t do what he did.”

But despite his reach and accomplishments, Jackson’s political chapter remains one of the least understood. For all that he achieved his campaigns have faded from the nation’s memory.

“Because he lost,” Phillip said. “When you don’t win, it’s easy for history to pave over what you did. That’s natural, but it’s also the purpose of writing history: to uncover what’s been papered over.”

Part of that erasure, she added, came as Jackson’s story was overtaken by Obama’s election in 2008 as the nation’s first Black president.

“That took over the narrative,” Phillip said. “But people who really know understand that Obama wouldn’t have happened without Jesse Jackson — in more ways than one.”

But in spite of Jackson’s outgoing public persona, Phillip discovered that his private life revealed a lifelong search for belonging.

As a child in South Carolina, Jackson learned that the man he believed to be his father was not. His biological father, Phillip writes, was a neighbor who lived next door with another family.

“He grew up looking over the fence at that family, feeling a sense of rejection. That yearning for belonging and fatherly affirmation carried into adulthood,” Phillip said. “It led him to Dr. King’s side, it drove his ambition, and it mirrors the experiences of other figures, like Barack Obama, who wrote “Dreams from My Father” before running for president. Jackson had an authentic desire to make change, but also a deep desire to be recognized. When he said to young people, ‘I am somebody,’ he was also saying it to himself.”

Today at 84, Jackson “sees his work reflected in everything around him,” Phillip said.

“Talking to his family and others close to him, they acknowledge that he sometimes demanded more adulation than people were willing to give — especially after 2000, when things started to shift,” she said. “But I think now, he feels satisfaction.”

Jackson’s story, as Phillip tells it, is not one of defeat but of transformation. His campaigns in 1984 and 1988 forced a political system to make room for voices it had long ignored and set the stage for a generation of leaders who followed.

In essence, it’s the story of a man who never won the presidency but changed who could.

IF YOU GO

“Elson Lecture featuring Abby Phillip in conversation with Ambassador Andrew Young.” 7 p.m. Nov. 5. Free-$12. Atlanta History Center, McElreath Hall, 130 W Paces Ferry Road Atlanta, 30305. 404-814-4081. www.atlantahistorycenter.com/event/abby-phillip/