Andrew Young, Rachel Maddow revisit ‘Dirty Work’ of civil rights movement

In Rachel Maddow’s sprawling two-part documentary on Andrew Young, viewers see the 93-year-old civil rights legend, former Atlanta mayor and U.N. ambassador only twice. First, seated in the sanctuary of Ebenezer Baptist Church, tears welling as he recalls the death and funeral of his friend, Martin Luther King Jr., and again at the end of the film.

But although his face appears only briefly, his steady voice and presence saturate every frame of Maddow’s documentary, “Andrew Young: The Dirty Work.”

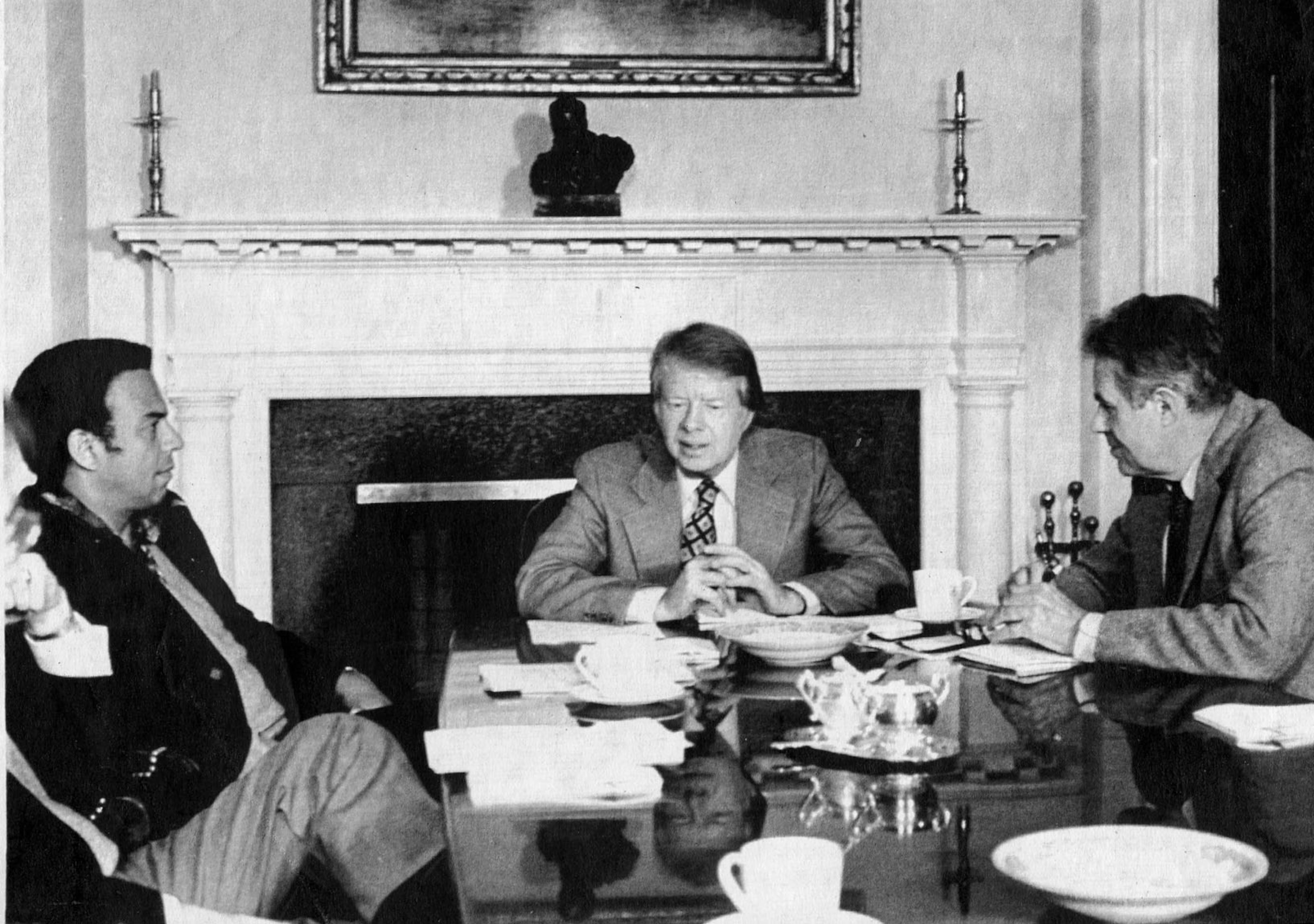

Using archival news footage, Young becomes his own narrator. He traces his life from the early years as a pastor and strategist alongside King to becoming the first Black congressman from Georgia since Reconstruction, and later as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations and mayor of Atlanta.

“I don’t think I’ve ever told my story altogether like this before. It’s more than I could have dreamed,” Young said. “At 93 years old, I’ve got 90 minutes of my life to look at.”

Maddow’s film explores how movements are built not only on soaring rhetoric and moral courage, but on what Young calls “the quiet, difficult labor that makes landmark change possible.”

“When I learned that Andrew Young might be willing to tell his story for this kind of project I was surprised,” said Maddow, the host of “The Rachel Maddow Show,” on MSNBC. “The opportunity to have him speaking in his own voice about the day-to-day work of his time in the Civil Rights Movement and beyond was surprising and exciting. It felt too good to pass up.”

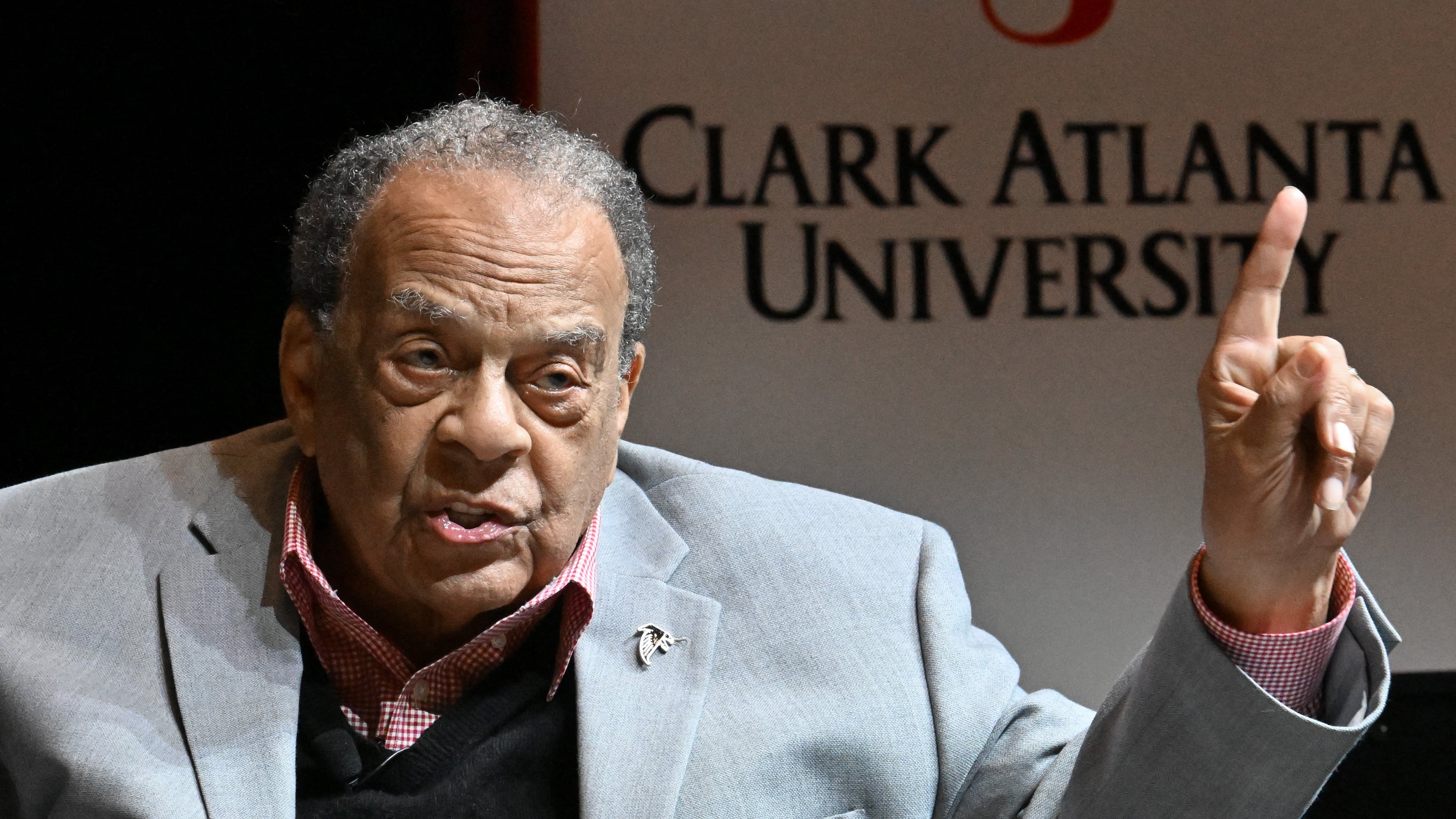

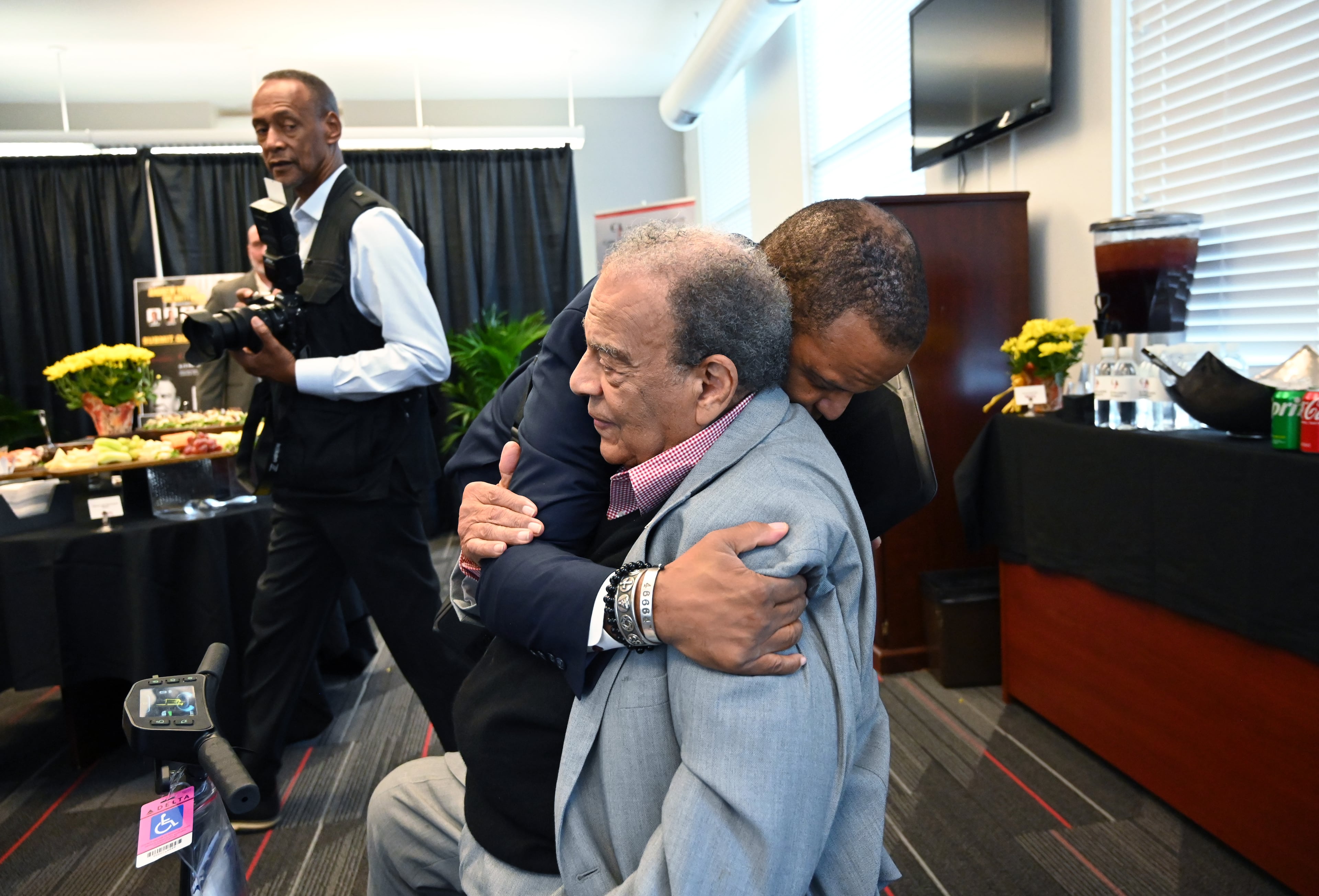

Maddow was in Atlanta on Tuesday, along with the Rev. Al Sharpton, to preview the documentary and host a fireside chat with Young and businessman John Hope Bryant at Clark Atlanta University.

Premiering Friday at 9 p.m. on MSNBC, the film will air immediately following a special edition of “The Rachel Maddow Show” dedicated to Young’s life and legacy. Directed by Matt Kay and co-produced by Left/Right, the documentary is executive produced by Maddow through her Surprise Inside production company.

The title comes from a phrase Young often uses to describe his work in the Civil Rights Movement with King.

“When there was something that needed to be done and nobody wanted to do it, that was my job,” Young said in the documentary. “That’s what I call the dirty work.”

Sharpton said Young’s dirty work “made America clean.”

In the film, Young reflects on the uneasy roles he sometimes played within the Civil Rights movement, including “Uncle Tom” assignments, which were the difficult meetings and negotiations with white officials that King asked him to take on for the greater good.

The film also examines a possible assassination attempt in South Africa while he was a U.N. ambassador, and revisits the 1979 controversy that led to his resignation after an unauthorized meeting with a Palestine Liberation Organization official. It also captures his emotional response and speech after the bombing of Centennial Olympic Park during the 1996 Olympics.

Maddow said that although “The Dirty Work” is historical, it is also instructional and pressing.

“What’s urgent is having a realistic understanding of what it means to work in a pro-democracy movement when your opponent is the government — and when the odds are stacked against you,” Maddow said.

She notes that the day after the film’s debut, more than 6 million Americans are expected to join “No Kings” rallies across the country — protests aimed at the Trump administration and its immigration enforcement policies.

“We’ve romanticized movements like that,” Maddow said. “But the truth is, these movements weren’t just about speeches and bill signings. The organizing took sacrifice, discipline and heartbreak.”

From the stage Tuesday night, Young watched as Sharpton introduced key scenes from the film.

“Every time I see a part of it, I see something I didn’t know,” Young said, adding that he has not seen the full film yet. “I’ll probably watch it by myself. Because I might start crying.”

While much of the footage has been seen before, Maddow’s team unearthed rare moments that are sometimes tender and at other times raw, violent.

Images of Young singing or playing tennis are juxtaposed with scenes of chaos — tear gas filling the air around him and Stokely Carmichael.

Then there is the excruciating moment in June 1964 in St. Augustine, Florida, when he was beaten by members of the Ku Klux Klan while trying to lead a nighttime march. Almost like a crestfallen boxing announcer, Young narrates every blow he received.

He later said the beating lasted much longer than what appears on film. But nobody died, and everyone got back to the church.

The beating, widely covered by the media, intensified pressure on President Lyndon B. Johnson to enact meaningful legislation.

Just a month later, on July 2, Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, outlawing segregation in public places and banning employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin.

“That was the most successful ass-whipping I ever received,” Young said in the film. “If I have to take a few licks and kicks to get a civil rights bill, I’ll do it any day of the week.”

Maddow — considered one of the most influential journalists in America — said working with Young humbled her.

“This project made me more appreciative, at a human level, of the risks people take when they stand up against tyranny,” Maddow said. “Maybe it’s me getting older, but I feel more mature about how I think of activism now.”

At the end of the film, wrapped in a scarf, hat and overcoat, Andrew Young sits in Centennial Olympic Park — the gleaming monument to one of his greatest civic achievements.

He flashes his familiar, easy smile and offers a few closing thoughts. His voice, deeper and raspier now than the higher-pitched “young Young” heard in the archival footage, still carries the same cadence and conviction.

“Freedom is a constant struggle, and we used to say that we’ve struggled so long that we must be free,” Young said. “Eh, I feel very free.”