Why the Atlanta Race Massacre mural sparks a heated community debate

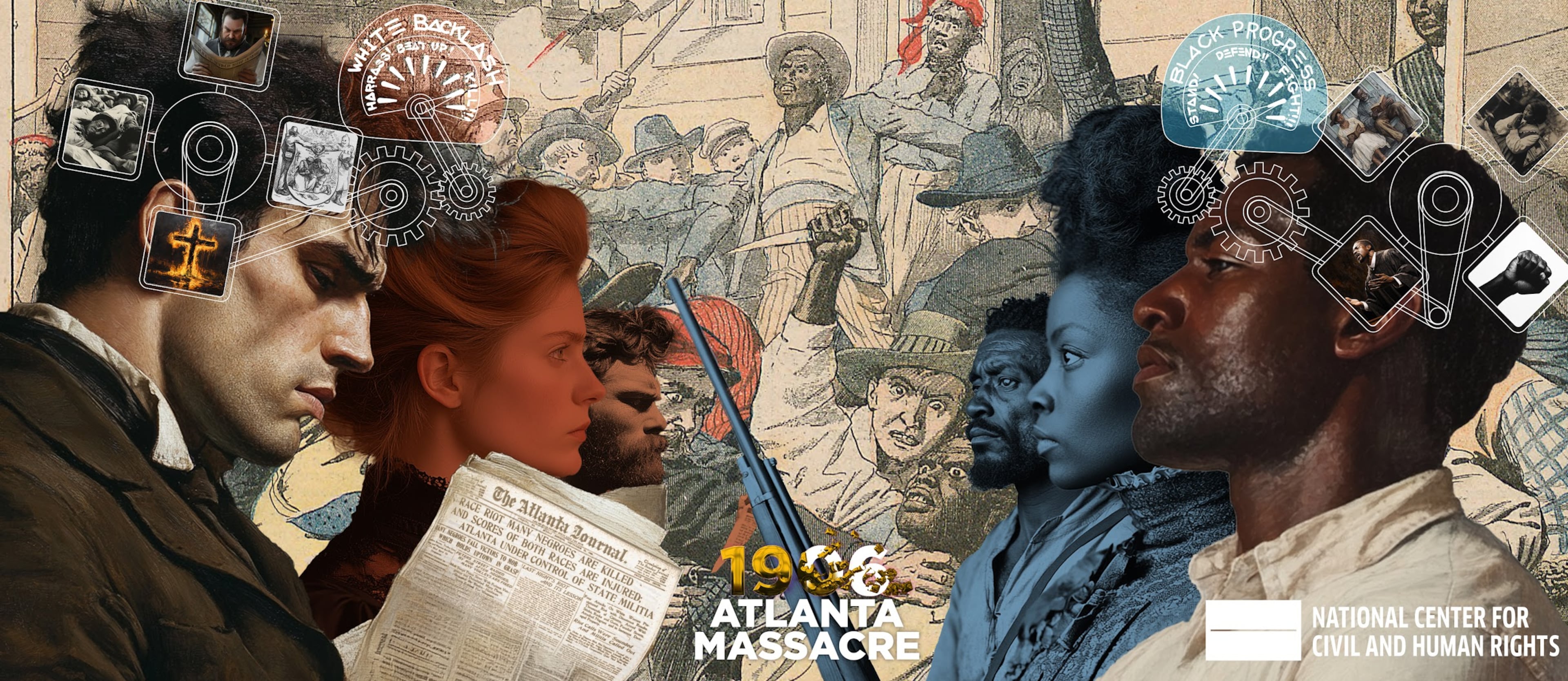

A mural commemorating the legacy of the 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre has drawn contention with its portrayal.

Though some residents have praised the painting as an acknowledgment of a discriminatory incident that resulted in the death of dozens of Black people, others have denounced the violent imagery and the lack of community involvement in the project.

The mural has raised the question on the proper way to share historical accounts and at what emotional expense.

“How do you make something horrible good?” 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre mural artist Fabian Williams asked. “If this was in, maybe, history books and was a part of American curriculum, maybe the mural wouldn’t be necessary.”

The mural was commissioned by the National Center for Civil and Human Rights, which worked with historical preservation group Coalition to Remember the 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre, nonprofit Focused Community Strategies and other agencies to get the project up and running. Williams, who said he did rounds of research to come up with ideas, said he wanted to approach the project with some historical sensitivity. He wanted to display the truth while also illustrating community heroes to really show the perseverance of Atlanta.

“I have a feeling and understanding of how things are perceived because I put myself in the viewers’ shoes,” Williams said.

National Center for Civil and Human Rights chief program officer Kama Pierce noted that Williams was chosen as the artist for the project because of his vast understanding and interpretation of history.

“It was really important for the (center’s) Truth and Transformation team — and for the museum — to have a local artist,” she said.

Enlisting the help of 12 other artists in Atlanta, Williams said the project was initially slated to be finished within three months. However, it took more than a year to be completed.

“I’m trying to figure out ways to reach people that cannot be reached otherwise,” he said, adding his best method of communication is visual art.

Williams’ initial ideas were not chosen for the mural, however. After 19 iterations, organizers finally decided on the design.

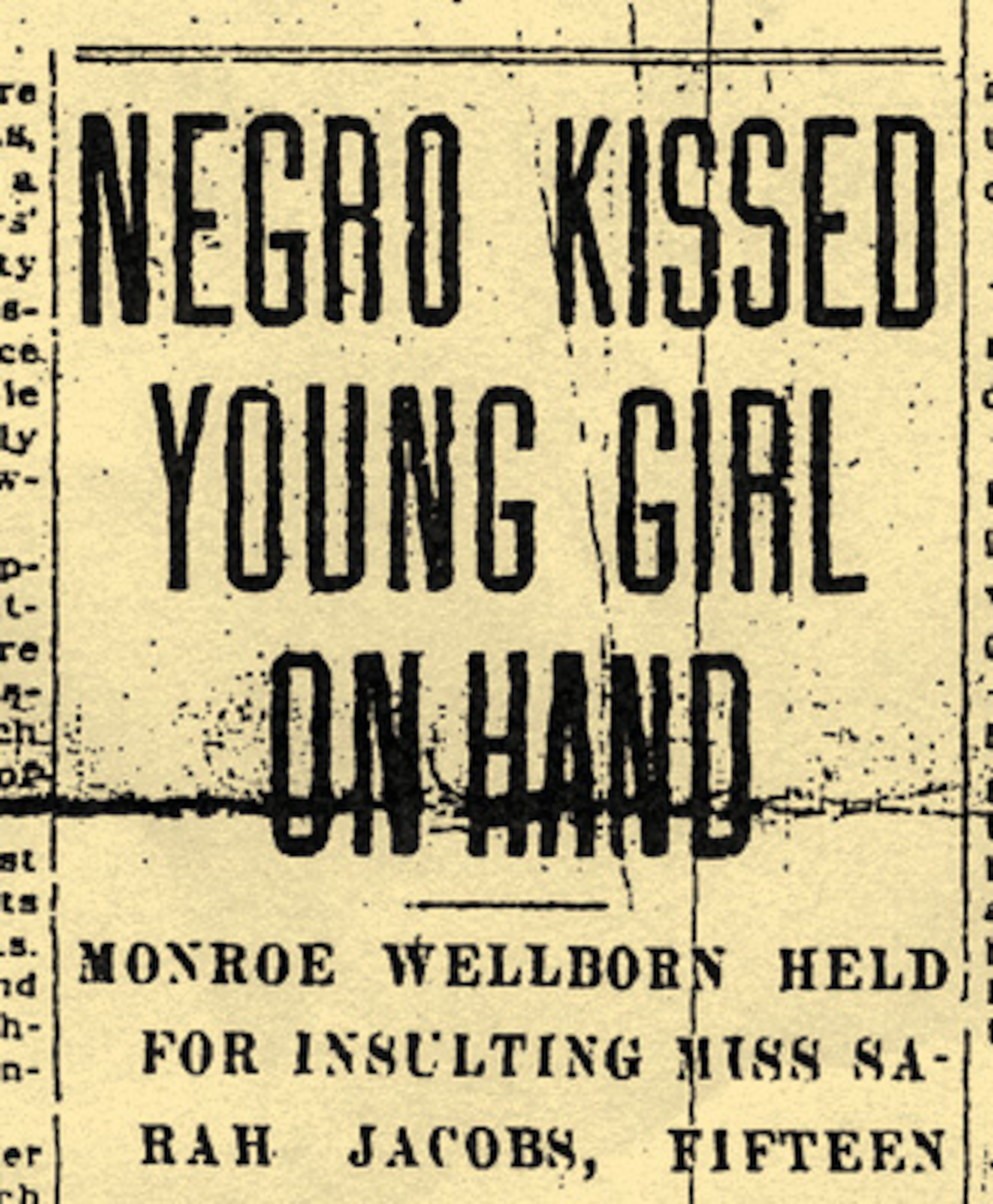

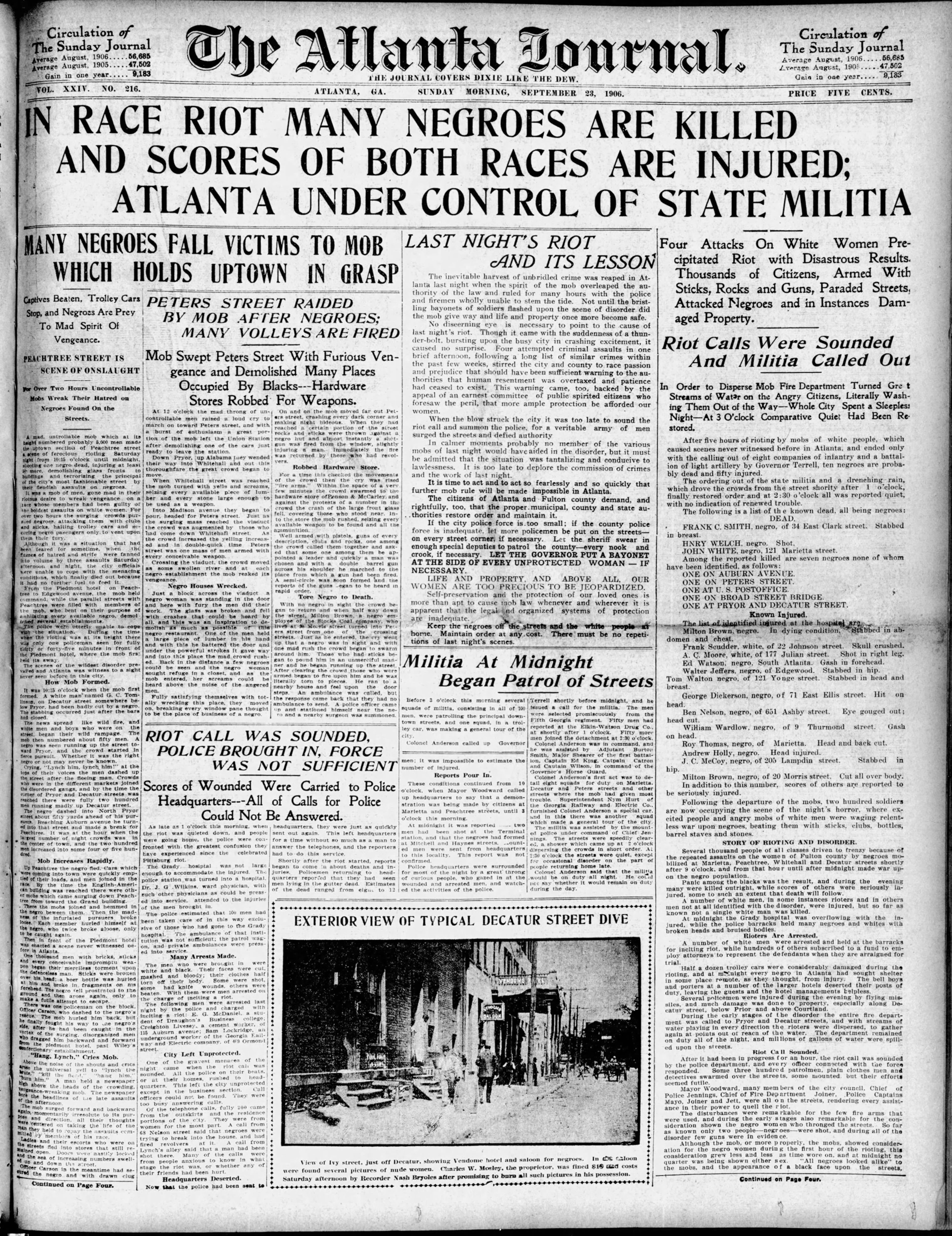

The race massacre began after unfounded news reports accused a Black man of assaulting a white woman. Over the span of four days, white mobs attacked Black neighborhoods in Atlanta.

“ (A white crowd) went on a killing spree,” said Ayinde Summers of the historic community organization Project South. “They traveled from Five Points all the way down to Brownsville, where they were stopped.”

Armed Black residents firmly stood their ground in the neighborhood now known as south Atlanta.

At least 25 Black people were killed during the massacre, and hundreds of others were arrested. One white man was killed.

On Sept. 26, a mural that pays homage to the massacre was unveiled on the backside of the Focused Community Strategies building on Jonesboro Road. The painting reads like a picture book. Starting at the left side, Black families build homes after migrating to Atlanta. The focal point shows an angry mob and a white man choking a Black man, an image taken from a French newspaper at the time of the massacre. To the right of the violence, the mural indicates Black progress despite the damaging and fatal mayhem that wrecked their neighborhoods.

Shawn Crittendon from Clayton County took her granddaughters to see the mural before it was finished.

“It’s always good when you see history and you see what happened,” she said, adding that she and her granddaughters researched the massacre after viewing the mural. “You’ve got to fight. You know you can’t just let anything happen when it comes to politics.”

Crittendon, who had never before heard about the race massacre, considered the overall experience to be enlightening.

Her 9-year-old twin granddaughters, Bella and Aris, agreed that history needs to be transparent.

“ (White attackers were) afraid that the Black community would become rich, successful, powerful — more powerful than them,” Bella said.

“I kind of felt happy because they were putting the truth out there,” Aris said.

Bella added that she felt a “surge of happiness” seeing Black artists painting the mural, while Aris was proud of their dedication to the project.

“It really looked great,” she said. “I liked seeing that it was different, like different parts of what happened in the massacre.”

Although the mural made some people proud that the story was being told, it left others conflicted about what was being shown in a historic community.

Robert Thompson, the resident historian of the Luther Judson Price house illustrated in the mural, said the painting was insulting because it didn’t convey the standoff by Black men to the oncoming white mob in Brownsville.

“If you look at the mural, you can never tell that 200 Black men were gathered and made a stand,” he said.

He said it would’ve been more accurate if the mural of the white man choking a Black man was downtown instead.

South Atlanta native Brenda Trammell said she would have preferred to have seen the neighborhood’s rich education history. The original campuses of Clark Atlanta University — then separate institutions Clark College and Atlanta University — and Gammon Theological Seminary were in the area.

“Let’s live and learn, not let’s fight,” she said. “I mean, I understand about history. We want to be reminded of it, but that just wasn’t the right image.”

Ann Hill Bond, a preservationist and community chair for the Fulton County Remembrance Coalition, was upset community members and activist organizations weren’t involved during the entire process for the planning and execution of the mural.

She said that after the artist was chosen, there was no more community engagement from the National Center for Civil and Human Rights.

“That is just a huge misstep on so many levels,” Hill Bond said, adding that the community was surprised to see the reveal of the mural.

“The truth doesn’t need retraumatization,” she continued. “There’s no resistance on that mural.”

Williams said he knew the stark image of white people attacking Black residents would draw ire from community members, despite the National Center for Civil and Human Rights choosing it over his other ideas.

“I wanted to show what happened before, what happened during and then what happened after, which led to the Sweet Auburn District, which was like Black Wall Street,” Williams explained. “Sweet Auburn turned into the Black business district. That’s where Ebenezer Baptist, Martin Luther King’s church, Wheat Street Baptist, all these other businesses that were important to the Black community that really made Atlanta what it was.”

He also said he presented options to paint Atlanta and civil rights heroes, but those ideas were overlooked.

A representative for Focused Community Strategies said the organization’s involvement in the project came later and had no part in choosing between the mural designs.

However, both the Coalition to Remember the 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre and the National Center for Civil and Human Rights accepted ownership for not continuing engagement with the south Atlanta community.

Pierce also acknowledged that art can vary in interpretation.

Now, the organization is determining a path forward.

“Going back, in hindsight, if we do this again — when we do this again, there probably needs to be more, deeper conversation with the neighbors. Absolutely.”