New book resurrects legacy of reparations pioneer Audley ‘Queen Mother’ Moore

When the historian Ashley D. Farmer began conducting dozens of interviews for her first book, “Remaking Black Power: How Black Women Transformed an Era,” one name surfaced again and again: Audley “Queen Mother” Moore.

“I met her at a rally,” some people told her. “She’s the first person I ever heard talk about reparations,” others said, describing Moore as a woman who changed how they understood Black nationalism.

Farmer — a Spelman College graduate and associate professor of history and African and African Diaspora Studies at the University of Texas at Austin — has built her career chronicling Black women radicals who refused to accept the limits of racism, sexism or capitalism.

The more she heard Moore’s name, the more she wondered why so few others had.

Over the next decade, while pursuing other projects, Farmer followed the faint traces Moore had left behind: letters tucked into unrelated archives, anecdotes buried in interviews, stray mentions in pamphlets and newsprint.

When she finally pieced enough together to tell the story, she was astonished that someone who had lived nearly a century — a witness to and participant in every major chapter of the 20th-century Black freedom struggle, who moved in the same circles as Paul Robeson, Malcolm X and Marcus Garvey — had no serious biography and had largely been forgotten.

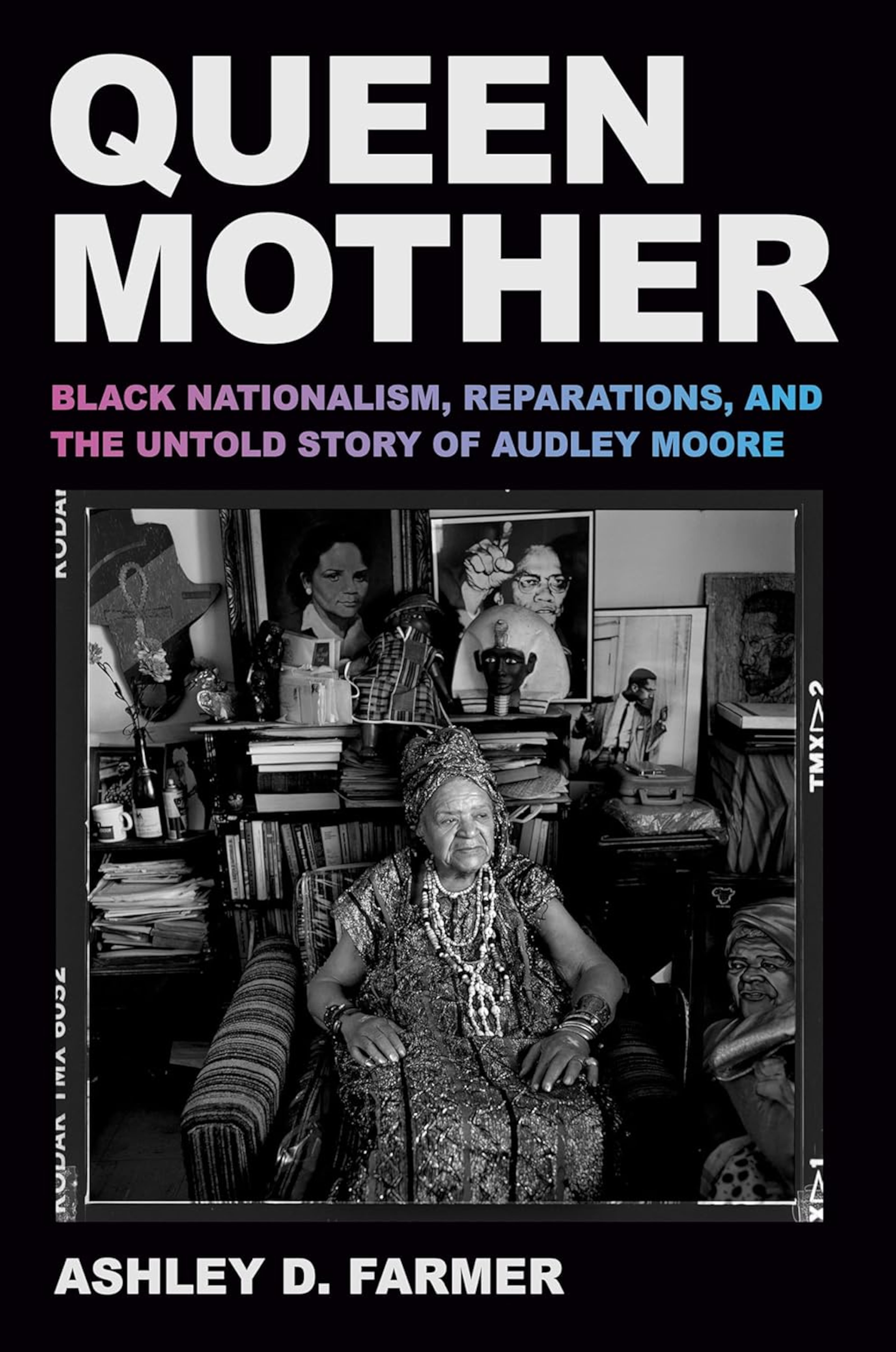

Her new book, “Queen Mother: Black Nationalism, Reparations, and the Untold Story of Audley Moore,” sets out to correct that omission, reconstructing the life of a woman who eluded easy classification.

“She didn’t fit neatly into the ‘liberty and justice for all’ narrative,” Farmer said. “We like our Black freedom leaders to be young, male and fixed in time. Moore didn’t fit that mold.

Farmer’s biography, released Nov. 4, arrives as Moore’s ideas — particularly around reparations — have once again entered the national conversation.

Next Monday, Farmer will discuss the book at Atlanta’s Auburn Avenue Research Library with Akinyele Umoja, a professor of Africana Studies at Georgia State University who knew and worked with Moore.

Umoja said Farmer’s book fills “a missing part of our movement’s history.”

She noted that Moore was part of the Garvey movement in the 1920s and the Communist Party in Harlem in the 1930s. Umoja first met Moore in 1972 as a college freshman.

“She lobbied members of the Black Power movement in the 1960s. And you can see her influence today in the more than 100 U.S. cities that now have reparations initiatives,” Umoja said. “That’s a triumph of her quiet organizing and lobbying.”

Born in 1898 in Louisiana to a formerly enslaved father, Moore witnessed the horrors of lynching and Jim Crow and became a committed activist after hearing Garvey speak in 1922. She died in Philadelphia in 1997.

When Farmer began looking for her story, she found almost nothing — no archive, no collection of letters, barely a mention in academic literature.

In one photograph that now appears on the book’s cover, Moore, draped in bracelets and necklaces, sits surrounded by stacks of books, files and photographs.

“But nobody knows where any of it is,” Farmer said. “She had no formal archive. There was no place where you could go to find her papers or belongings.”

To fill in the gaps, Farmer relied on what she calls “informed speculation,” stitching together details from broader contexts.

“It was a treasure hunt and a labor of love,” she said. “There’s joy in finding someone’s life out of order. It makes you think differently.”

One find lingers vividly in Farmer’s memory: a folder labeled “1966 School Boycotts.”

“Inside, the only thing was a poem handwritten by Queen Mother Moore,” Farmer said. “It wasn’t labeled or cataloged. Just there. Discoveries like that made the whole process magical.”

The portrait that emerges is of a Garveyite, a onetime Communist, a nationalist and a Pan-Africanist — a woman who called reparations “the linchpin of every other policy” and imagined a separate Black nation with its own institutions, culture and economy.

“She held radical views,” Farmer said. “Moore believed America was a failed democratic project and that Black people should separate, build their own nation, infrastructure, economy and culture, financed through reparations. Today reparations are less fringe, but her broader vision of separation still is.”

Farmer doesn’t shy away from how Moore’s values sometimes clashed with their actions.

Though she espoused patriarchal views about women’s roles, she lived in open defiance of them, leaving three husbands behind and forging her own path.

But Moore’s open admiration for Ugandan dictator Idi Amin, whom she once described as “warm, beautiful and sweet,” was harder for Farmer to process.

Between 100,000 and 500,000 people were killed under Amin’s brutal regime, earning him the nickname “the Butcher of Uganda.”

“It broke my heart to realize how her personal obsessions sometimes blinded her to mass violence,” she said. “But I had to tell the truth on the page to show that even the most committed activists can be caught up in contradictions.”

The project also became personal for Farmer, whose scholarship centers on radical Black women “who did not want to keep up with the status quo of racism, sexism and capitalism.”

A 2006 Spelman graduate, Farmer traces that commitment — and her scholarly confidence — to her time there, where she first learned that Black women were not only worthy of study but capable of reshaping how history itself is written.

“I try to expand our canon of who we think of when we think of leaders. Not just those who were organizing, but those who were coming up with new ways to live, to be free,” she said.

For Farmer, “Queen Mother” is more than a biography. It’s an act of historical recovery.

“For readers, I hope it expands their understanding of the Black freedom movement through the eyes of a Black woman on the ground,” she said. “Even if people don’t agree with her politics, Moore’s life shows what it means to stay the course and to devote yourself entirely to your beliefs despite financial or personal sacrifice.”

IF YOU GO

“Queen Mother: Ashley D. Farmer in Conversation with Akinyele Omowale Umoja.” 6:30-7:30 p.m. Nov 17. Free or $40.68 (includes book). Auburn Avenue Research Library, 101 Auburn Avenue Northeast, Atlanta, GA 30303. eventbrite.com