At the end of print, the AJC confronts its history and plots its future with Black Atlanta

On the morning of March 23, 2023, staff members at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution were summoned to a hastily called mandatory meeting.

Some crowded into a conference room; others logged in by video.

Kevin Riley, the paper’s editor for 12 years, was there to make official what many had already suspected: He was retiring.

What followed was not expected.

Andrew Morse, the AJC’s president and publisher, told the staff there would be no interim editor and no prolonged national search. The decision, he said, had already been made.

Leroy Chapman, a managing editor who had been at the paper since 2011, would take the helm.

The room fell silent, then erupted in gasps, applause, tears.

Chapman, who had overseen coverage of some of Georgia’s most consequential stories, including efforts to overturn the state’s 2020 election, had just become the first Black top editor in the newspaper’s 155-year history.

“That moment was one of those things you can’t really prepare for,” he said in an interview. “I didn’t realize in that moment just how affirming it would be — not only for Black journalists, but for a city like Atlanta that defines itself by inclusion and diversity. Atlanta has long been the place where, if you’re Black, talented and ambitious, you can get a fair shot.”

Inside the newsroom, the celebration landed as both a milestone and a mirror reflecting how far the paper had come and how contested its relationship with Black Atlanta had long been.

That history takes on fresh urgency now as the AJC prepares to sunset its print edition at the end of the year. The AJC, Morse says, is evolving into a modern media company and redefining local news. It is doing it in a national moment where diversity and inclusion are being attacked.

The newspaper is reassessing what it has meant to Black readers, how it has covered race, and how the slow work of hiring Black journalists — from Harmon Perry in 1968 to a new generation of storytellers — has shaped its credibility.

For much of their existence, Atlanta’s daily newspapers reflected a social order enforced by Reconstruction and Jim Crow. The Atlanta Journal and The Atlanta Constitution of that era, long before they merged into the AJC, were white institutions built to serve white readers.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Henry Grady and other editors helped to shape a “New South” narrative that promised economic modernization while openly defending the racial order.

During the 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre, four white-owned daily newspapers, including the Constitution and the Journal, printed sensational and unverified stories about alleged assaults by Black men, stoking the panic that helped trigger white mob violence.

Through the Jim Crow era, the papers largely reinforced segregation by writing about Black Atlantans through a lens of crime, paternalism or invisibility.

That dynamic did not fully shift during the civil rights movement, but it did evolve.

As Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff document in “The Race Beat,” the Pulitzer Prize-winning history of news coverage of civil rights, the Constitution distinguished itself from other Southern papers by adopting a more moderate editorial stance and by acknowledging, often cautiously, that segregation’s foundation was cracking.

Klibanoff, a former managing editor at the AJC, said that under Ralph McGill, the paper broke the Southern taboo against speaking frankly about racial violence. He wrote moral arguments against segregation that other white editors refused to touch, even if he stopped short of endorsing the movement’s goals outright.

In excerpts from “The Race Beat,” in 1938, in his first directive as executive editor of The Atlanta Constitution, McGill declared that henceforth the word Negro would be capitalized whenever it was used.

Klibanoff said McGill “may have been the first editor in the South to abandon the common practice among journalists in the region of writing the word with a lowercase n.”

Former Atlanta Journal-Constitution editorial page editor Cynthia Tucker, a native of Alabama, said McGill’s reputation traveled far beyond Atlanta — and mattered deeply to Black readers who were accustomed to far harsher treatment from the white press.

“If you read his columns today, they can seem tepid. But for that time and place, they were courageous. He was calling out segregationist figures when many others wouldn’t,” Tucker said. “Ralph McGill’s willingness to treat Black people with a degree of civility earned the Constitution a lot of trust among Black readers.”

McGill’s protege, Eugene Patterson, authored the blistering 1963 editorial “A Flower for the Graves” after the Birmingham church bombing and read it that night on national television.

Their work helped to set a moderate regional tone, showing that a white Southern daily could report honestly without being torn apart by readers or advertisers.

Yet even as the Constitution gained national praise for its editorials, the reporters who filled the daily news columns remained almost entirely white.

The Constitution did publish a weekly section put together by educator Claude George called “News of Our Negro Community” and covered the Civil Rights Movement, but it largely failed to cover the lives of the Black majority in Atlanta.

It quoted Martin Luther King Jr. and Ralph Abernathy on its pages, but rarely chronicled the lives of the everyday people those men represented. That gap grew more glaring as Atlanta’s Black population surged and racial change accelerated.

Black families and businesses were far more likely to appear in the Black-owned Atlanta Daily World than in the pages of the Journal or Constitution.

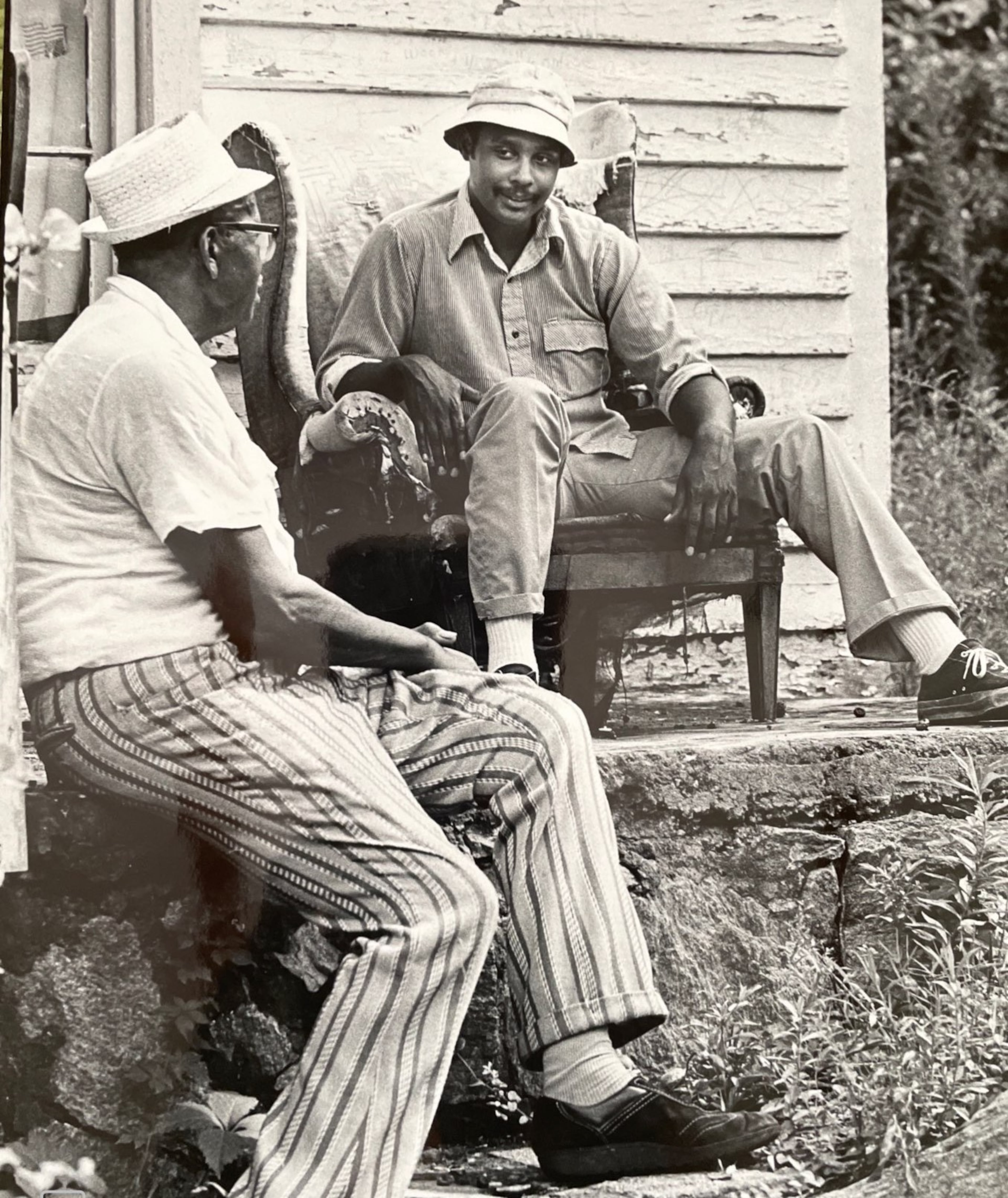

It wasn’t until 1968 — in the wake of urban uprisings the presidentially appointed Kerner Commission concluded were the results of systemic racism — that the Atlanta Journal hired its first Black reporter, Harmon Perry.

Perry came from the Atlanta Daily World, where he had already earned trust in neighborhoods the Journal often struggled to cover. His hiring signaled that the paper was beginning, however tentatively, to reckon with the city’s demographic and political realities.

His first assignment was covering King’s funeral.

To his daughters, the “first” was both history and something more ordinary.

“I remember him being excited about getting the position because he felt like he had gone as far as he could go with the Atlanta Daily World,” his oldest daughter, Philippa Elder, said in an interview. “And he kind of considered himself a little trailblazer. And he was.”

In 1988 — 20 years after Perry was hired — his youngest daughter, Phyllis Perry, joined the Atlanta Journal on the copy desk and later rose to Cobb County bureau chief.

Phyllis Perry said her father’s hiring still reads as a door opening, even if he never seemed to embrace the symbolism in the way others did.

“The mere fact that he was doing what he was doing opened the door for me,” she said. “But he never wrote anything about that period. I am not sure it meant that much to him.”

But Pete Scott, who followed Perry to the Journal in 1971 as a general assignment reporter, noted those early days could be rough.

He remembers a staff meeting that he and Perry attended where an editor whose name long escaped him noted — perhaps as a joke — that the paper now had two Black people.

“I don’t know if he said Black, but he said, ‘We had two of them,’ or y’all, or something like that,” Scott recalls the editor saying. “One of you is gonna fill out the quota and the other one is gonna be the token.”

A photojournalist at heart, Perry stayed at The Atlanta Journal for only five years. In 1973, he resigned to become the Atlanta bureau chief for Jet magazine.

Scott stuck around until 2005, retiring after 34 years, one of the longest tenures ever for a Black reporter.

“I worked from about nine in the morning to about 11 at night every night. I never left if I had an assignment,” Scott said. “I did a lot of trailblazing stuff for the paper that it didn’t necessarily get credit for. But I was a pretty good reporter.”

Although Perry’s and Scott’s hirings cracked open the door, it took years before a sustained team of Black journalists emerged.

In 1971, Tina McElroy Ansa joined the Constitution as an editorial assistant before becoming a reporter, becoming the first Black woman to enter the newsroom. She died last year.

In 1972, the Journal hired Chet Fuller, who spent 26 years as one of the most influential voices in the newsroom, covering politics and neighborhoods before later becoming a columnist and eventually assistant managing editor.

“When I describe those newsrooms to students, it might as well be Reconstruction,” said Tucker, who was hired by The Atlanta Journal right out of Auburn University in 1976. “It wasn’t hostile, but it could be awkward. But if I didn’t know something, I’d ask. People were generally helpful.”

As the newspapers slowly began to diversify their newsrooms, Atlanta itself was undergoing a political transformation.

In 1972, Andrew Young was elected the first Black congressman from the South since Reconstruction.

The following year, Maynard Jackson became Atlanta’s first Black mayor.

One of the reporters who arrived as the newsroom began to take shape was Alexis Scott, who joined The Atlanta Constitution in 1974.

In 1928, Alexis Scott’s family founded the Atlanta Daily World, a legacy that allowed her to see, from both sides, what Black Atlanta expected from the white press and what it still depended on the Black press to provide.

Alexis Scott said that simply showing up mattered.

“It meant a great deal. People felt they could trust our reporting because they saw us as Black people working for the white press,” Alexis Scott said. “Although we saw ourselves as journalists who happened to be Black.”

Alexis Scott spent 23 years at the AJC and Cox Enterprises before retiring in 1997 to take over her family’s business, the Atlanta Daily World.

Others, like Ernie Reese, who covered Black college sports, Ernie Holsendolph, who covered Black business, and Shelia Poole, who covered religion and stayed at the paper for 35 years — the longest tenure ever for a Black staffer — followed.

Meanwhile, Tucker was making history of her own.

In 1992, she became the first African American editorial page editor of The Atlanta Constitution. She became editor of the combined editorial pages in 2001, emerging as one of the country’s most prominent journalists — and one of the most consequential figures in the paper’s history.

Tucker said her job was to “take Ralph McGill’s legacy and push it further,” a charge she carried out with a sharp, fearless voice that helped to reorient the AJC’s editorial stance on race, politics and public life — even when it meant taking on Black politicians or the family of Martin Luther King Jr.

“As a Black woman who grew up in the Deep South and who was working as an editorial page editor in the Deep South, it was easy to criticize racism. But I thought it was important for me to also challenge Black establishment figures whom I believed had gone off course. It was important for me to say those things,” Tucker said. “It was easier to do that in Atlanta than it would have been in many other cities. Black Atlantans had achieved so much by the time I became editorial page editor that they didn’t feel nearly as threatened as they might have in cities where less progress had been made.”

In 2007, largely because of her work writing about race and attacks on voting rights, Tucker earned a Pulitzer Prize for commentary, becoming the first and only African American AJC staffer to win journalism’s top prize.

Following Tucker’s example, by the 1990s and 2000s, the pipeline of Black reporters had strengthened as increased Black enrollment in journalism schools and changes in hiring practices brought more diversity into the field.

That new generation would go on to shape the paper’s modern coverage of civil rights, race and Black culture, even as the paper experimented with structured race and identity beats.

In the days after his appointment, Chapman sat for an in-house interview with the staff of Unapologetically ATL, the AJC’s African American-centered weekly newsletter.

He was asked what, if anything, his leadership would change about the paper’s coverage of Black life and Black issues.

“As a Black journalist, you carry a responsibility to bring the perspective of Black America into the newsroom. That’s what inclusivity is,” Chapman said. “We want to understand needs, aspirations, obligations around opportunity and outcomes.”

That conversation became an early signal of how Chapman intended to lead. Soon after, he approved the AJC’s first full-length documentary, “The South Got Something to Say,” an Emmy-nominated exploration of Atlanta’s hip-hop legacy.

He also expanded Unapologetically ATL into a standalone franchise — now known as UATL — extending its reach beyond a weekly newsletter to community events, social media, video and podcasting.

“If the future of local news is deep engagement and direct relationships with readers, we know there’s a hunger for strong reporting on Black culture, HBCUs, and navigating Atlanta. UATL speaks to that ethic,” Chapman said. “It’s reflective of who we are now and where we’re going.”

Tucker, now retired and serving as a journalist-in-residence at the University of South Alabama, said her view of the paper’s record comes with a caveat.

“We did better than many. Not perfect — but I’d give us a B-plus,” she said. “A lot of progress came because Black reporters and editors fought for it. Any newsroom legacy on race has to acknowledge that.”

For readers like Thomas Cochran, the end of the printed paper is not simply a technological shift, but the quiet loss of a daily ritual — and, to a certain extent, a civic tool.

Cochran, 77, a retired computer specialist and longtime AJC subscriber in Fairburn, has spent decades cutting out articles, filing them and carrying their lessons into his community work.

“The AJC gives me information I can use to inform our Black community,” he said. “It’s become my habit. I get up in the morning and I read my paper. Reading it on the phone just doesn’t work for me. Going to the computer doesn’t feel the same. I’ll miss being able to take the paper, sit on my deck or in my bed, and read it comfortably. That’s a luxury.”

Earlier this month, Chapman found himself seated at the end of the fourth row at the Tara Theatre. Onstage were Nedra Rhone and Najja Parker — two original founders of Unapologetically ATL — joined by DeAsia Paige and Brooke Leigh Howard.

The quartet serve as hosts of the UATL podcast, the AJC’s newest entry into the crowded audio landscape.

More than 200 people — most of them Black women — filled the theater to watch “The Best Man Holiday,” listen as the hosts unpacked the film’s themes and greet Chapman.

Many had come not simply to consume journalism, but to experience it — and to encounter the AJC in a more communal, participatory way than the printed page had ever allowed.

It was a quiet but visual testament to how a newspaper once encountered by readers like Cochran at breakfast tables was now being met in theaters, conversations and shared space.

“We’ve transformed from being just a daily newspaper into something broader — podcasts, films, live events — speaking to audiences in the ways they want to be reached,” Chapman said. “When I’m in rooms like that, my presence becomes part of the connection people feel to the AJC. I understand that desire for connection, and I’m proud we’re able to meet it. I’m seeing the future.”