Hosea Williams at 100: A civil rights legacy lives on through service

On Monday, as Atlantans gather with the rest of the nation to honor the life of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., a warehouse on the city’s southwest side will quietly mark another milestone in the long arc of the Civil Rights Movement.

The occasion is both practical and symbolic: a day of service organized by Hosea Helps and Delta Air Lines, timed to the centennial of Hosea L. Williams, one of King’s closest and most fearless lieutenants.

Williams, a street-level organizer known as much for confrontation as compassion, would have turned 100 on Jan. 5, a milestone his family and supporters are marking by linking his civil rights legacy to direct service in the communities he spent his life fighting for.

“This year is special,” said Elisabeth Omilami, Williams’ daughter and the president of Hosea Helps. “A lot of young people coming up now don’t remember him. They don’t know what he stood for. And with everything going on in the world — his message of peace, of not giving up, of pressing through no matter what — still applies.”

Williams marched alongside King in the 1960s, then spent much of the latter half his life focused on poverty, believing that civil rights victories meant little if people remained hungry, unhoused and desperate.

Born in 1926 into extreme poverty in rural southwest Georgia, Williams survived a childhood marked by instability, a near-fatal beating by white men upon returning from World War II and a lifetime of physical injury after surviving two battlefield explosions.

Those experiences hardened his resolve and shaped his approach to activism. He would later become one of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s most aggressive tacticians, often sent into volatile towns to mobilize communities, pack jails and force confrontation.

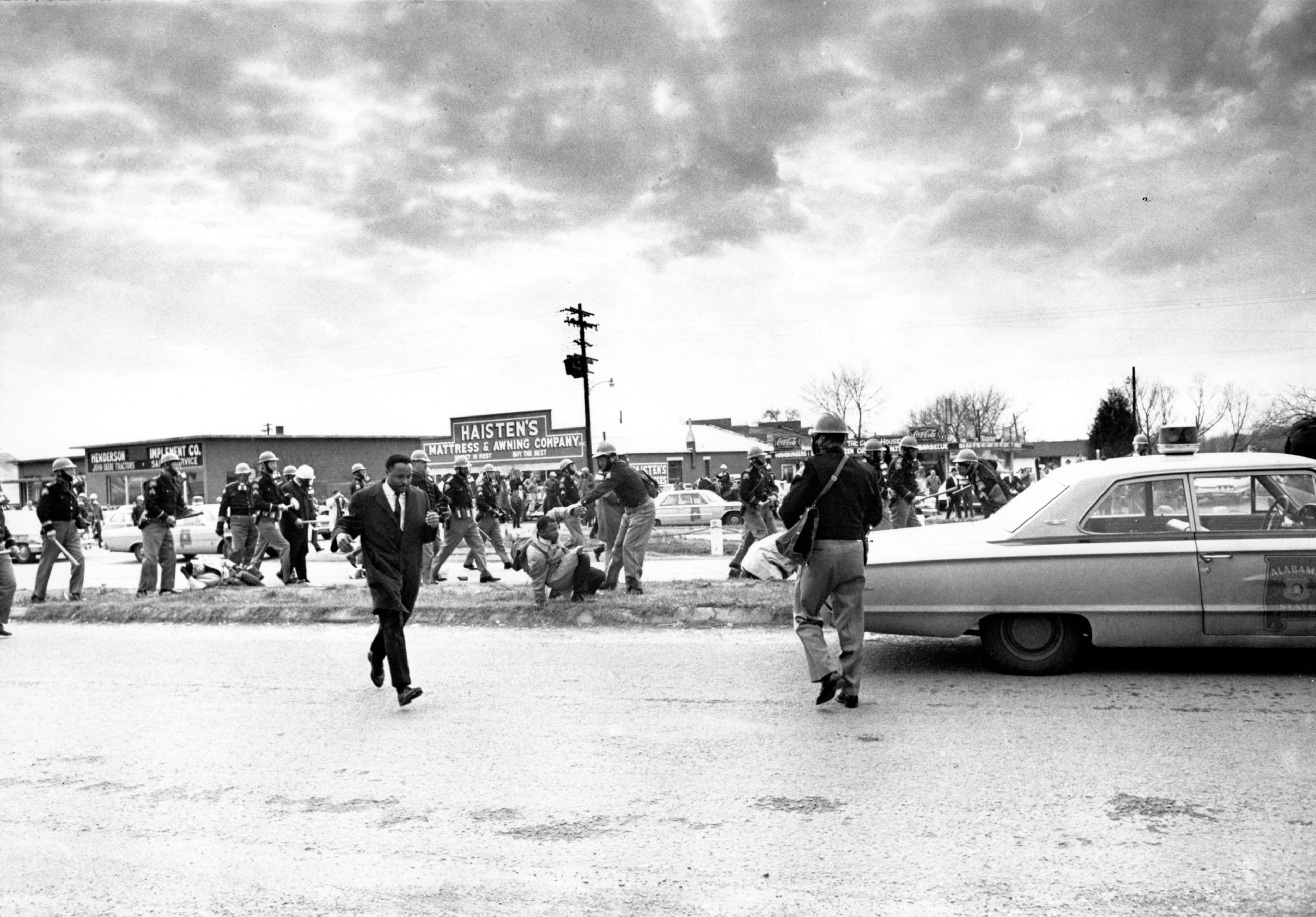

His defining moment came on Bloody Sunday, March 7, 1965, when he and John Lewis led marchers onto the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. The violence that followed, broadcast nationwide, helped galvanize public support for the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Historians and allies have said Williams’ willingness to step into that first wave helped accelerate the law’s passage.

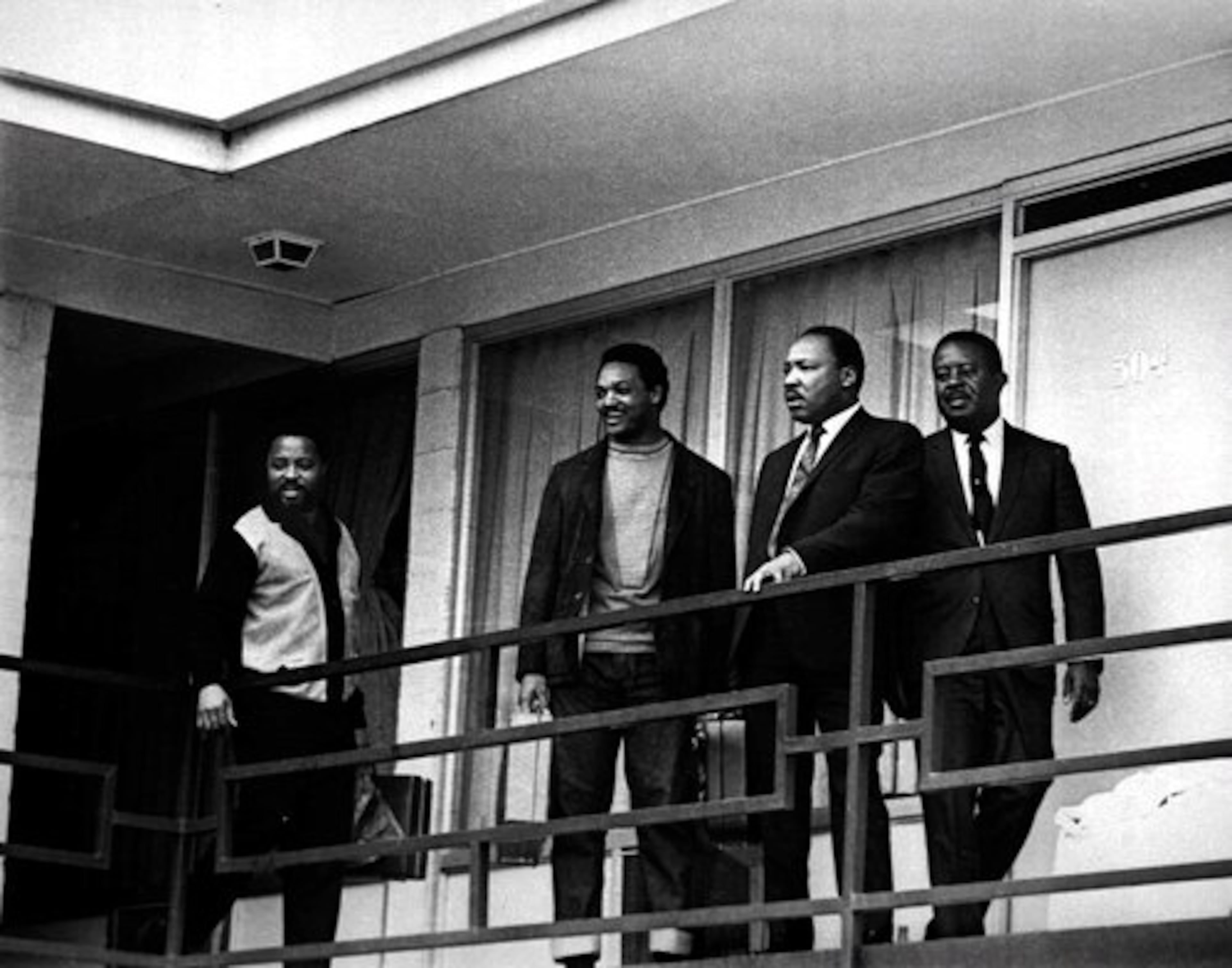

On April 4, 1968, Williams was in Memphis, Tennessee, when King was killed.

Days later, dressed in denim overalls, he helped lead King’s mule-drawn casket through the streets of Atlanta.

Like many of King’s aides after the assassination, Williams searched for ways to continue his work. In 1970, after witnessing a homeless man rummaging through a trash can for food, he decided to focus on hunger.

He founded Hosea Feed the Hungry at Wheat Street Baptist Church, serving a single meal to about 100 homeless men. More than five decades later, the effort has grown into a year-round operation serving thousands across metro Atlanta.

“He believed freedom didn’t mean much if people were still hungry or losing their homes,” Omilami said. “That’s why this work still matters, especially on Dr. King’s holiday.”

This year’s King Day event, called the Delta Air Lines Community Table, will run on Monday from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. at the Hosea Helps campus on Forrest Hills Drive and serve hundreds of people.

Preregistered guests — particularly those who are unhoused or unable to cook — will receive hot meals, while additional families will be served through a drive-through distribution of grocery boxes stocked with fresh produce, meat and water. Students will also receive school supplies, and teenagers will be eligible for gift cards.

The event will also include free barber and beautician services, access to the organization’s clothing center for children and adults and raffles sponsored by Delta with prizes such as laptops and gaming systems.

Health care will be a central component of the day. In partnership with Grady Health System, Hosea Helps will offer a mobile mammogram unit and screenings for blood pressure, cholesterol, glucose, HIV and hepatitis C, along with help enrolling in programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children — known as WIC — and guidance on job readiness.

“This is so necessary,” Omilami said. “People don’t always have access. If we can bring it to them for one day, that can make a real difference.”

The scale of the event reflects what Omilami describes as her father’s belief in faith in action. Williams pushed ahead with marches and relief efforts even when funding was uncertain, trusting that support would follow.

For decades, Hosea Feed the Hungry operated hand-to-mouth, driven by his urgency and charisma — scrambling for donations, food and space, often at the last minute — imperfect and unpredictable, but enduring.

“There were times he didn’t care what was in the bank,” Omilami said. “He pressed on anyway, and then the donations would come, the volunteers would come. That’s something I carry with me.”

In 2000, the man who proudly called himself “unbought and unbossed” died from cancer. He was buried in his familiar denim overalls, red shirt and red sneakers, a look that had become synonymous with his public life.

Omilami took over the organization after her father’s death and is marking her 25th year leading it. She and her husband, actor Afemo Omilami, stepped away from their acting careers to do so. They are now gradually shifting more responsibility to their son, Awodele Omilami.

Under her leadership, the organization has been professionalized into a year-round operation providing daily food assistance, rent and utility support and emergency aid.

The faces have changed. Poverty now includes families who have never needed help before, new immigrant households and people one missed paycheck from collapse.

Preventing homelessness has become one of the organization’s most urgent priorities.

“It’s so hard to bring people back once they fall into homelessness,” she said. “Rent assistance, utility help — those things matter.”

That focus will be on display on King Day, continuing a 56-year effort guided by the belief shared by King and Williams that service and justice are inseparable.