Ronald McNair and the day the future broke

On Jan. 27, 1986, Carl McNair was back home in Atlanta with his father and his pregnant wife, having returned from Cape Canaveral after waiting days for the launch of the space shuttle Challenger.

The mission was scheduled to lift off Jan. 22, but technical problems and unseasonably cold weather kept pushing the launch back. After repeated delays, the family returned to their Southwest Atlanta home.

Ronald McNair, Carl’s younger brother, stayed behind. He was assigned to the flight as a mission specialist.

Their mother, Pearl McNair, uneasy about her son flying into space, stayed behind to watch the launch.

Back home, Carl McNair did not realize Challenger had been rescheduled for early the next morning, Jan. 28 — a clear, but cold Tuesday.

By the time he turned on the television, all he saw were plumes of white smoke drifting across the sky above the launchpad.

Earlier that morning, his wife, Mary, told him she felt their unborn daughter kick for the first time.

“Maybe there was a passing of a baton,” Carl McNair said.

A grim anniversary

Four decades later, the Challenger explosion remains one of the most searing moments in American history.

Seven astronauts died in what would be the first catastrophic loss of a space shuttle crew — an event that shattered the belief that spaceflight had become routine.

Jan. 28 marks the 40th anniversary of the disaster, a milestone that still reverberates across NASA and the nation.

It unfolded live before millions of Americans — from schoolchildren gathered around classroom televisions to students at Black colleges packed into student unions to watch one of their own.

For much of his adult life, Ronald McNair carried two futures at once: one unfolding far above the Earth inside NASA’s space shuttle program, the other rooted in South Carolina, where he imagined raising children and teaching.

Both futures ended abruptly on that cold January morning, when Challenger broke apart 73 seconds after liftoff.

Where it began

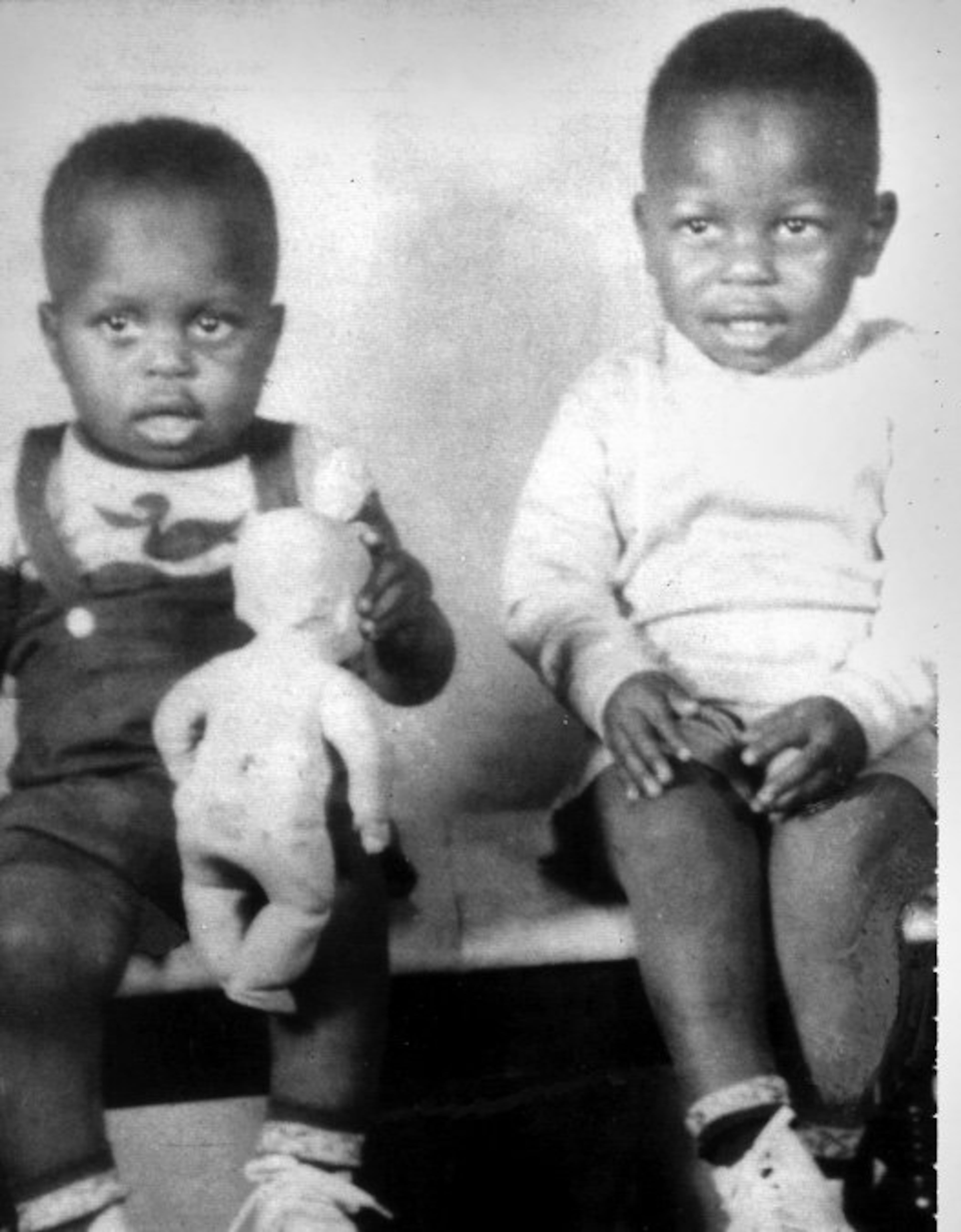

Ronald McNair was born Oct. 21, 1950, in Lake City, South Carolina, a place that offered few visible pathways into science or engineering. The McNairs were raised in their grandfather’s home on Moore Street, an aging wooden structure without indoor plumbing.

Ronald McNair was the middle of three brothers; Eric was five years younger, but Carl just 10 months older.

“We grew up like twins,” Carl McNair said. “Our parents dressed us up alike up until before we were teens — or until we rejected it.”

Their mother, Pearl McNair, taught in the segregated Black school system and centered education, church and family life.

Their father, Carl Columbus McNair, worked as an automobile mechanic and often spoke of his regret at not finishing high school, pressing his sons toward discipline and academic rigor.

By the time he was 3, Ronald McNair could read. He started school at the age of 4, and when he turned 5, he was placed in the same grade as his older brother, Carl. They were rarely separated.

The McNair brothers attended what Carl McNair described as “a little, old rinky-dink school,” taught by brilliant Black teachers who believed fiercely in education.

“They could have been engineers, physicians, anything,” he said. “But those opportunities weren’t available to them.”

In 1959, as a child in Lake City, Ronald McNair was denied permission to borrow books from the public library because he was Black. He refused to leave, and the police and his mother were called. By the end of the standoff, McNair was allowed to check out the books.

“Not to make him sound saintly, but Ron always tried to do the right thing,” Carl McNair said. “Folks could depend on him.”

Books piqued his imagination. So did what he saw on television.

“We grew up watching Star Trek and Lt. Uhura. She was wearing them hot pants in space,” Carl McNair said of the show’s only Black character. “We were able to see Black folk doing something that was unheard of when we were coming up.”

In 1967, the same year McNair graduated from high school, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. famously pleaded with Nichelle Nichols, who played Lt. Nyota Uhura, not to quit the show.

“For the first time, the world sees us as we should be seen,” King told her. “As equals, as intelligent people — as we should be.”

The Leap

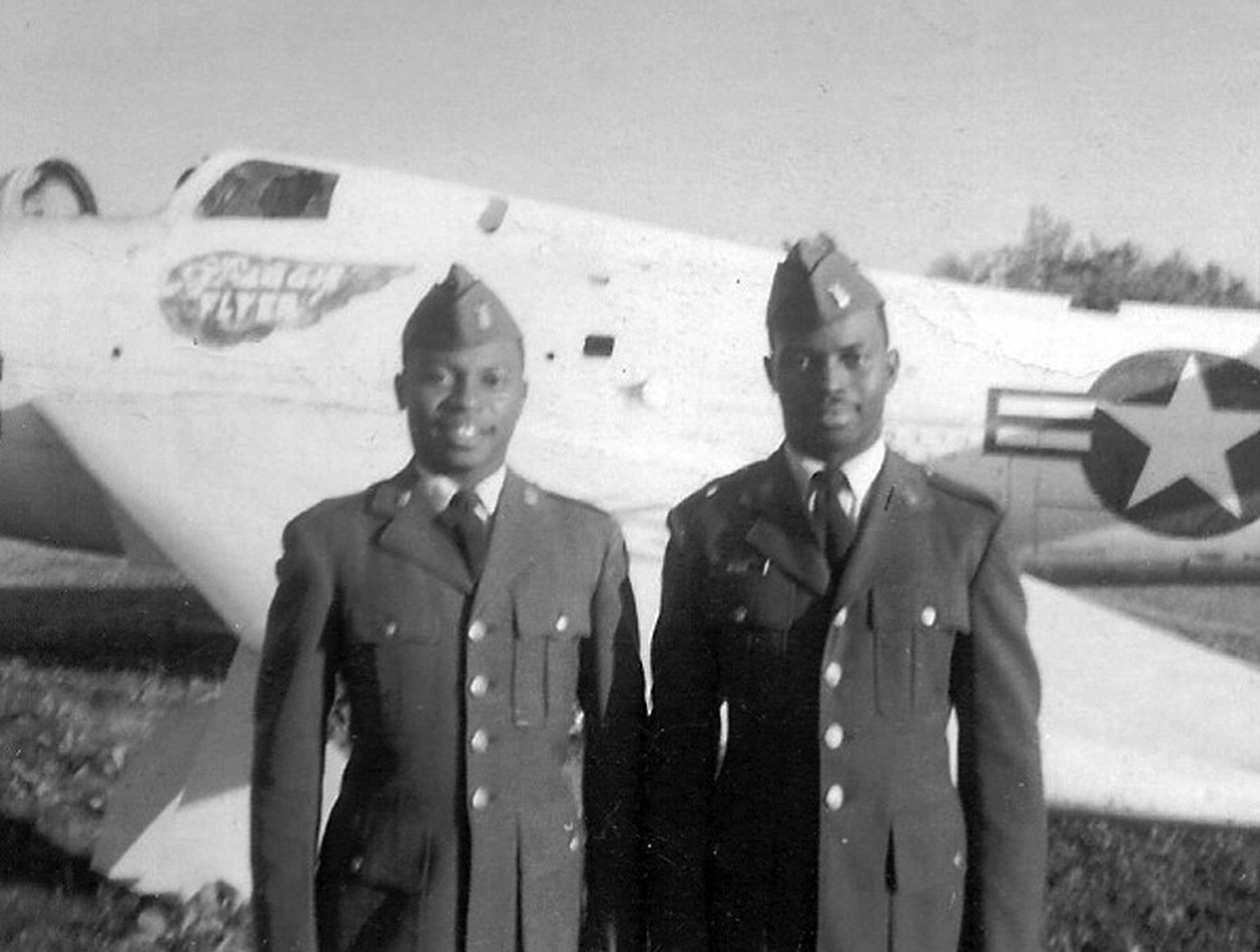

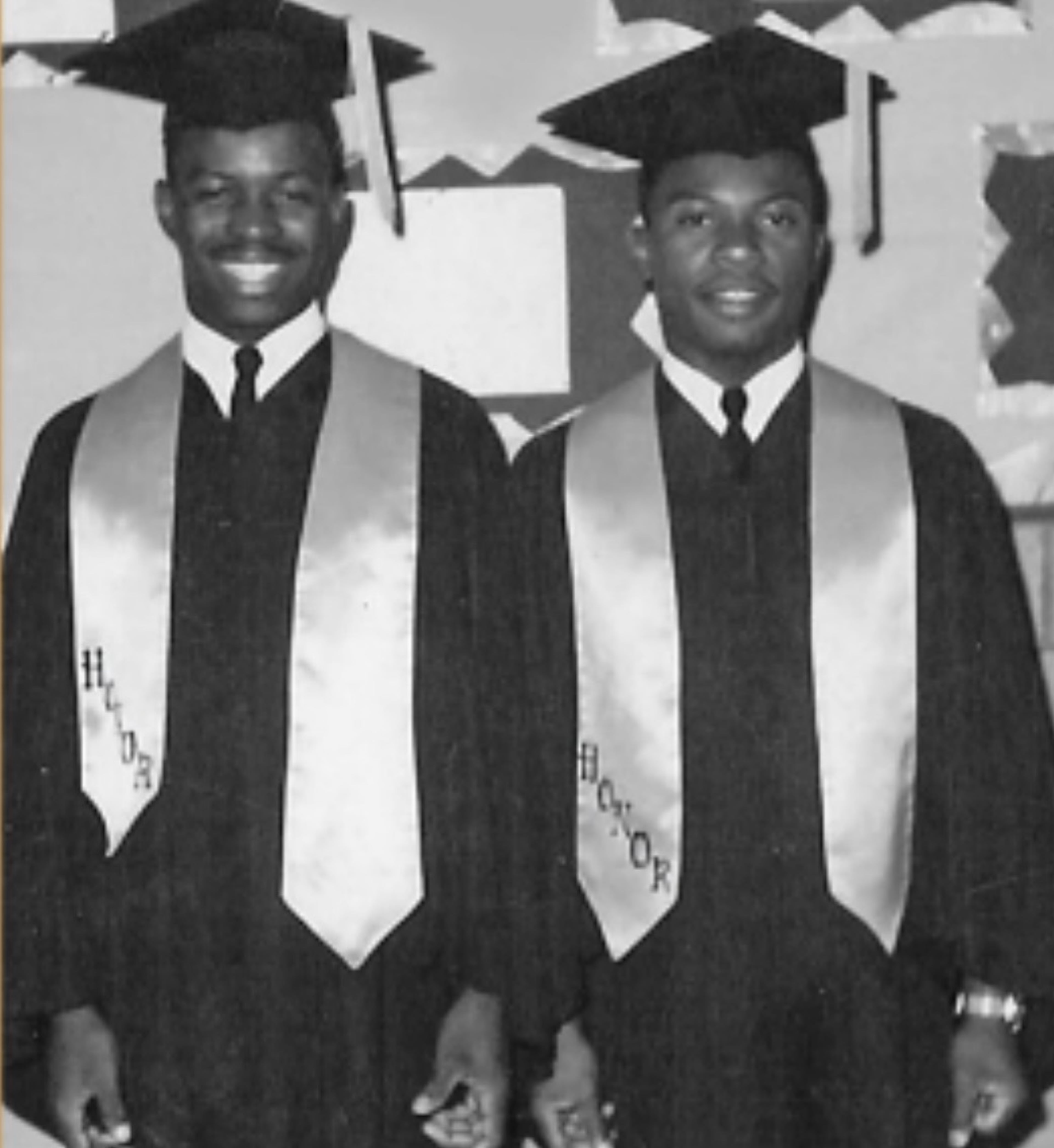

After graduating from Carver High School, the brothers traveled 200 miles north to enroll together at North Carolina A&T State University, a historically Black university with a strong engineering program.

At A&T, Ronald McNair initially chose physics but quickly realized how far behind his preparation lagged compared with students from elite Northern schools.

He retreated into the music department until his initial adviser, Ruth Gore, noticed. She called him into her office and patiently listened as he explained why he didn’t think he could succeed in physics.

Then, in a story as old as historically Black colleges and universities themselves, she told him that he was “good enough to earn a physics degree here. I want you to go try.”

“She believed in him at a time when he couldn’t,” Carl McNair said.

Ronald McNair majored in physics, played saxophone in R&B bands to earn spending money and earned a sixth-degree black belt in karate. In the fall of 1969, he followed his brother, Carl, who had pledged that spring, into Omega Psi Phi Fraternity.

The brothers graduated with honors from A&T in 1971.

Both brothers moved to Boston. Carl studied marketing at Babson College, while Ronald was accepted into the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s doctoral program in physics, graduating in 1976.

Afterward, Ronald moved to California to work at Hughes Research Laboratories.

‘I’m gonna be an astronaut’

One day in 1978, Ronald called his older brother.

“He said, ‘Man, I don’t know if I should tell you this,’” Carl recalled. “‘But I’m gonna be an astronaut.’”

Carl laughed. “OK, yeah, I’m gonna be the pope,” he replied.

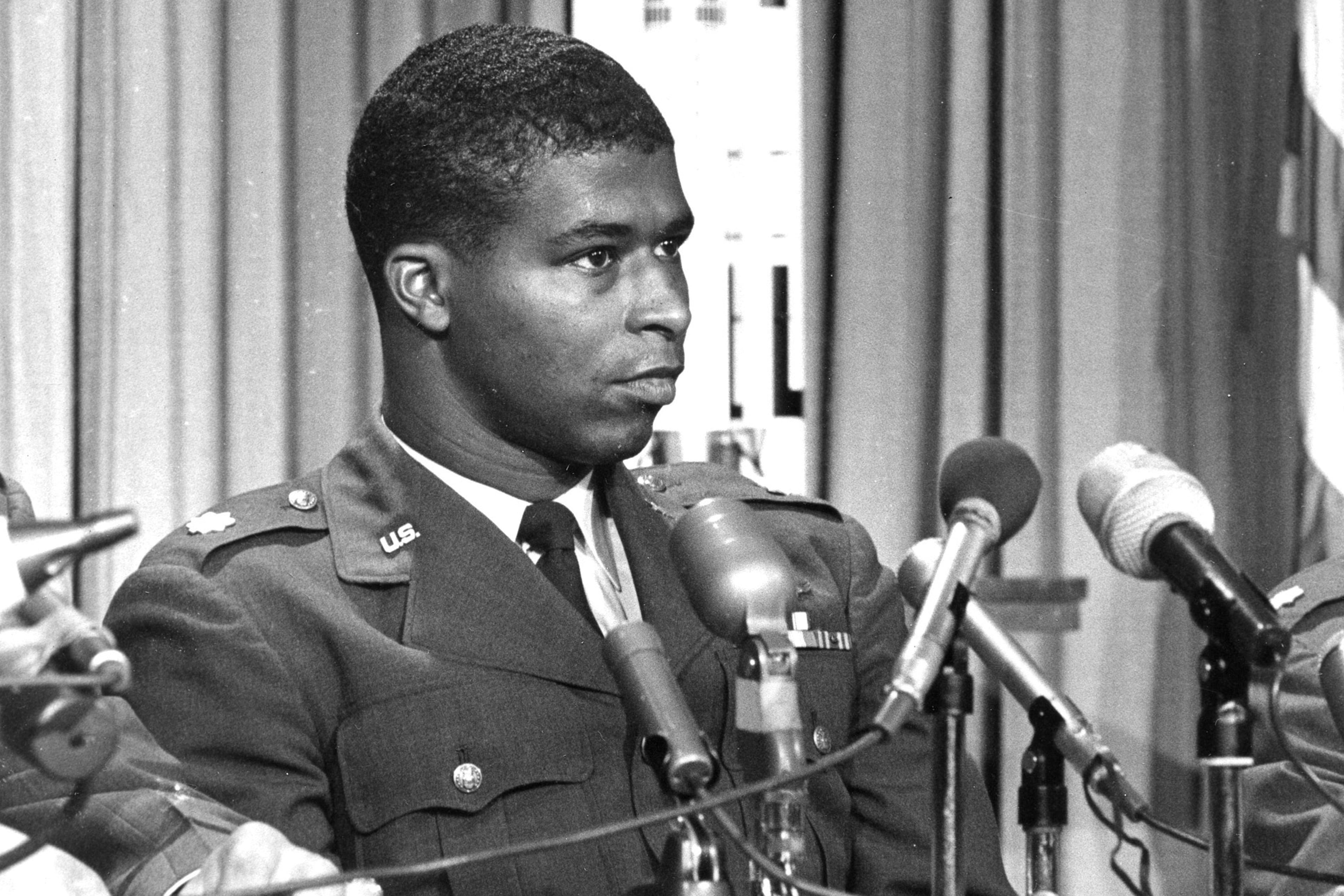

At the time, NASA had employed only a handful of Black astronauts, none of whom had yet traveled into space. Before 1978, NASA and the Air Force had selected 73 astronauts, nearly all of them white — men who looked like Neil Armstrong and Alan Shepard.

The lone Black astronaut, Maj. Robert H. Lawrence Jr., was killed in a training accident in 1967.

“For Ron to think he could be an astronaut then, it was ridiculous,” Carl McNair said.

The barriers were explicit: perfect vision, military test-pilot credentials and, as Carl put it plainly, “it looked like you had to be white.”

Ronald McNair was neither a pilot nor a military officer and lacked the credentials NASA typically favored.

“And just in case you didn’t notice, he was Black,” Carl McNair said.

What he did have — a background in laser physics — was exactly what NASA needed.

Class of 1978

A few weeks after Ronald McNair’s cryptic call, NASA announced he had been selected as one of 35 new astronaut candidates for the space shuttle program.

The Class of 1978 included six women, among them Sally Ride, who would become the first American woman to travel into space.

Along with McNair, two other Black men were selected: Maj. Frederick D. Gregory and Maj. Guion S. Bluford Jr. In 1983, Bluford became the first African American in space.

Four of the seven astronauts killed aboard Challenger were members of that same 1978 class.

‘That’s my brother up there’

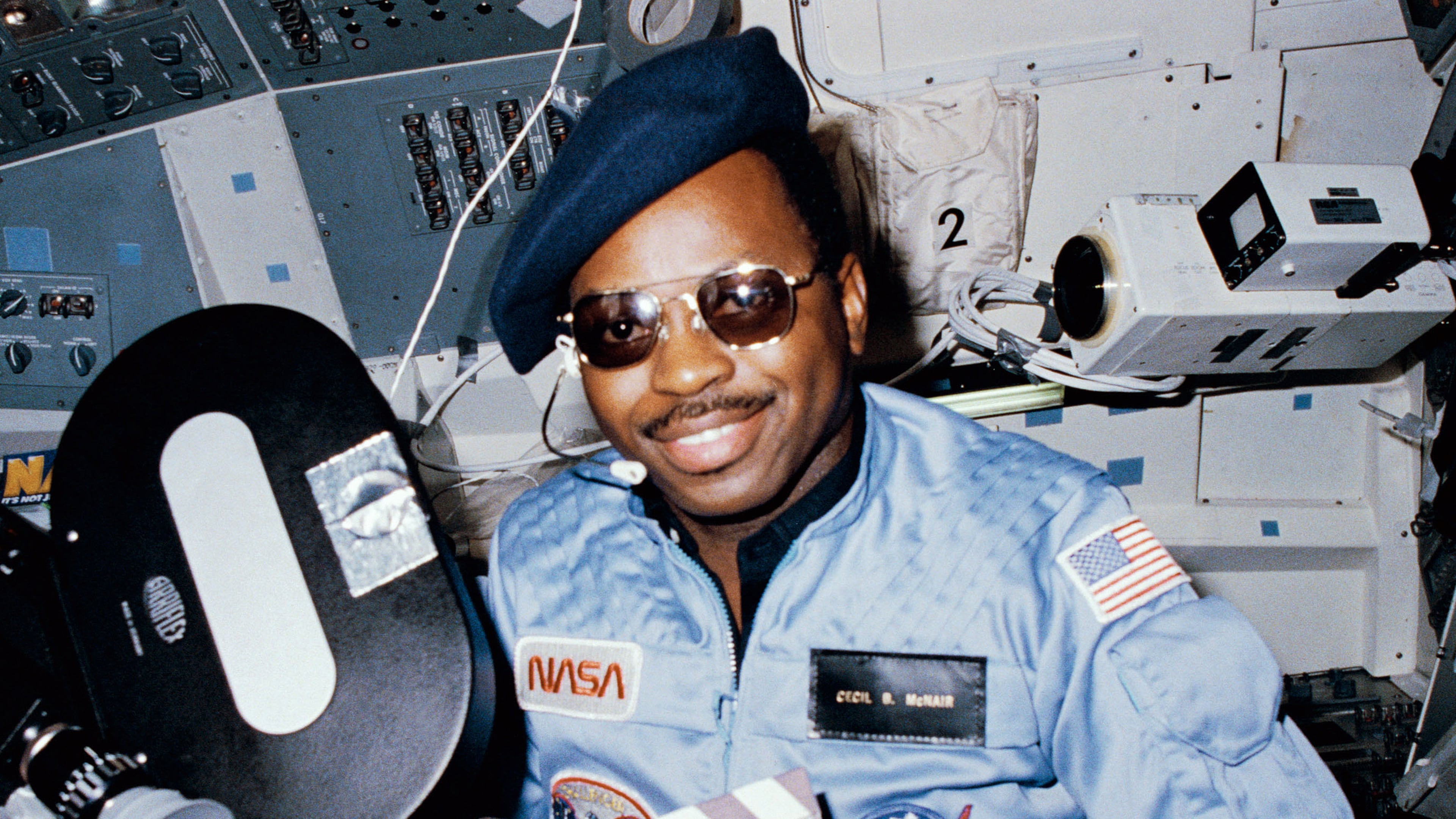

Ronald McNair’s first spaceflight came in February 1984, when Challenger carried him into orbit for six days. Only the second Black man in space, McNair orbited the Earth 122 times.

“All I could think was, ‘That’s my brother up there,’” said Carl McNair, who still gets emotional at the memory of that first flight. “He went up and came back down. It doesn’t get better than that.”

It seemed as if half of Lake City had made its way to Cape Canaveral to witness the launch in person. Back home, neighbors and friends gathered around televisions, making the moment a communal ritual.

Children who had never seen a Black scientist on television suddenly had one orbiting the Earth.

The image that lingered long after the mission ended was a saxophone tucked against Ronald McNair’s chest — a moment that carried cultural weight far beyond science.

“That was an iconic image for me,” said Naia Butler-Craig, who recently earned her Ph.D. in aerospace engineering from Georgia Tech. “I love that he showed you can be multipassionate, Black and excellent.”

Pride and fear

For Pearl McNair, the pride came braided tightly with trepidation. To her, space was not a frontier or a symbol of progress, but of distance and danger.

“She was never comfortable with him flying,” Carl McNair said. “Never.”

Faith anchored Pearl McNair, but it did not erase the fear. She prayed constantly and believed in her son’s brilliance. She just did not believe that space was safe.

A routine flight

The space shuttle program began on April 12, 1981, with Columbia’s first flight.

Less than five years later, NASA had already flown 24 missions, making this the 10th flight of Challenger. The mission, scheduled for January 1986, was to be Ronald McNair’s second spaceflight.

The mission’s headline was the presence of Christa McAuliffe, a high school teacher selected to become the first educator to fly in space.

Joining her and McNair were Francis R. Scobee, Michael J. Smith, Judith A. Resnik, Ellison S. Onizuka and Gregory B. Jarvis.

NASA framed the flight as routine. The weather told a different story.

Overnight temperatures were forecast to fall to 18 degrees, rising only to 26 degrees by the scheduled 9:38 a.m. launch.

In Atlanta, it was 7 degrees, the coldest temperature recorded that year.

73 Seconds

The Challenger lifted off from Cape Canaveral at 11:38 a.m., rising smoothly into the cold Florida sky as thousands of spectators — including Pearl McNair, her sister, Mary Christmas, and Ronald McNair’s wife, Cheryl, watching with their two young children — looked on from the ground, while millions more followed live on television.

Sixty-eight seconds after liftoff, Capsule Communicator Richard O. Covey told the crew: “Challenger, go at throttle up.”

In response — 73 seconds into the flight — Scobee, who was the flight commander, replied: “Roger, go at throttle up.”

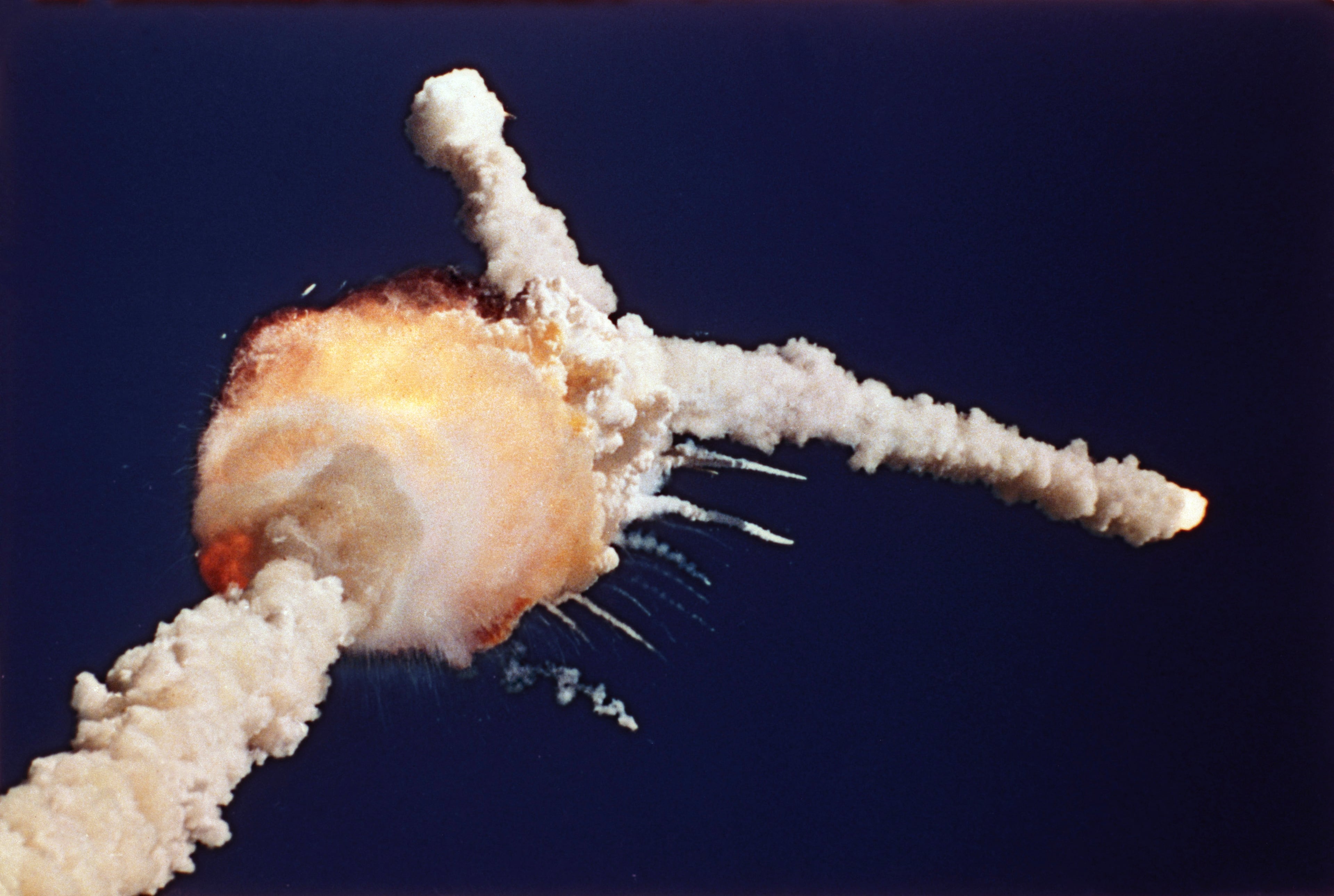

Challenger erupted into a fireball roughly 10 miles above the Earth, at a moment when both its main engines and solid rocket boosters were firing at full power.

Two white plumes arced away from the explosion, followed by a widening spray of debris that traced ghostly contrails across the blue sky.

For several seconds, onlookers could not grasp what they were seeing.

Flaming wreckage fell toward the Atlantic for nearly an hour, forcing rescue crews to keep their distance and leaving little doubt the crew had not survived.

“I didn’t see it happen live, but they just kept showing it,” Carl McNair said. “I thought it was science fiction. Then it hit me.

“Imagine seeing a loved one killed in a horrific accident over and over and over again.”

For Pearl McNair, who witnessed the explosion, the pain was different.

“She kept asking, ‘What happened? What’s happening?’” Carl McNair said. “And no one would tell her. My mother was never the same after that.”

NASA offered no explanation for the disaster and within hours suspended all shuttle flights indefinitely.

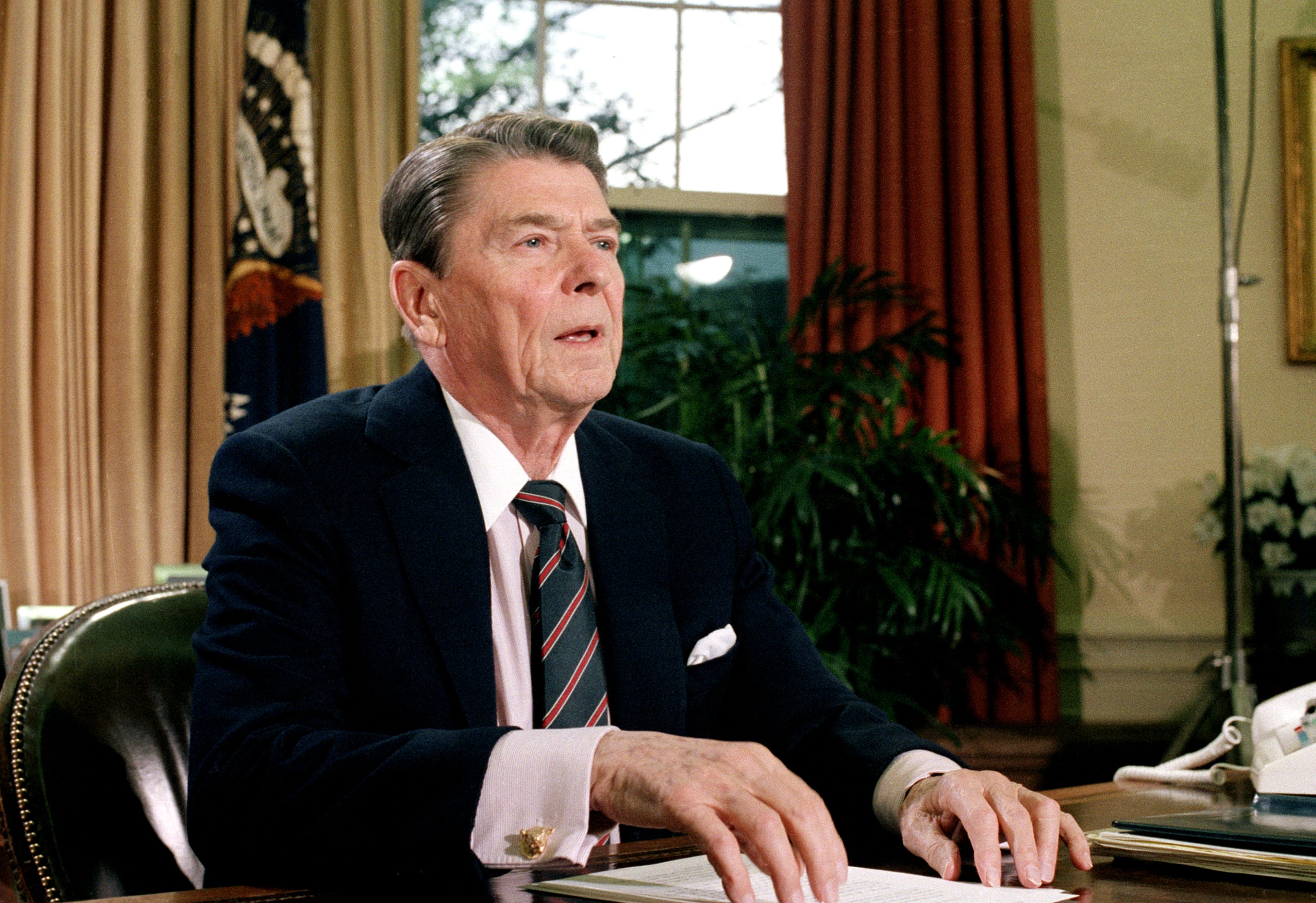

That evening, President Ronald Reagan canceled his State of the Union address and spoke instead to a shaken nation.

“We will never forget them, nor the last time we saw them as they prepared for their journey and waved goodbye and slipped the surly bonds of Earth to touch the face of God,” Reagan said.

“The future doesn’t belong to the fainthearted,” Reagan said. “It belongs to the brave.”

Aftermath

It took two months to recover the remains of the seven astronauts from the ocean floor, about 18 miles off the coast of Cape Canaveral.

On May 20, 1986, the commingled cremated remains of the Challenger crew were buried at Arlington National Cemetery, in a single grave: Section 46, Grave 1129.

It was an official closure — but not for the McNair family.

Memorials came in waves.

“It was like funeral after funeral after funeral,” Carl McNair said. “It got to the point I had to stop going.”

Before the Challenger flight, Ronald McNair had already been telling friends and family members that it would be his last.

Carl McNair said his brother planned to retire and was offered a job at the University of South Carolina to teach physics.

Anger

Anger followed grief.

The Rogers Commission, convened in the aftermath, found that Challenger was launched despite warnings from engineers about cold weather and the failure risk of the shuttle’s O-ring seals.

Concerns were raised, debated and ultimately dismissed. The report recast the explosion as a preventable tragedy — one born of institutional pressure and ignored expertise.

“The report showed folks went up the chain and decided to fly anyway,” McNair said. “Some flat out told them, ‘You launch this, you’re going to lose it.’ And they rolled the dice. They gambled on our loved ones’ lives.”

Living memorials

Today, Ronald McNair’s legacy endures.

Dozens of buildings, academic programs and schools bear his name, including three in DeKalb County.

Both M.I.T. and North Carolina A&T have buildings named in his honor.

At A&T, Ronald E. McNair Hall — named for the only astronaut in NASA history to graduate from an HBCU — is marked by a bust of McNair outside its entrance.

“He is a symbol of what we can do, what we can accomplish and what an Aggie can achieve,” said Shelly Lesher, chair of the physics department at N.C. A&T. “We have not forgotten him at all.”

Lesher, who remembers watching the Challenger disaster in grade school on a roll-in classroom television, came to A&T from the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse, where she directed a McNair Scholars Program.

The program represents one of Ronald McNair’s most enduring legacies.

Nationally, the McNair Scholars Program operates at more than 200 colleges and universities across the United States. More than 100,000 students — many of them first-generation, low-income and from historically underrepresented backgrounds — have passed through its ranks.

At North Carolina A&T, that legacy takes shape through the Ronald E. McNair Post-Baccalaureate Achievement Program, which guides students through undergraduate research and sustained mentorship toward doctoral studies.

They move through the same campus and hallways McNair once did — a daily reminder, said Chantal E. Fleming, the program’s director, that students preparing for academic careers are walking in the footsteps of someone who once imagined the same future and reached it.

“It is a source of renewed motivation, inspiration and encouragement as they move forward with purpose,” Fleming said.

Fleming hosted a symposium on campus last weekend honoring the life and work of Ronald McNair.

“We’re trying to build a living memorial,” Carl McNair said. “Not just monuments, plaques, murals. These programs change lives.”

‘The future belongs to the brave’

One of them is Naia Butler-Craig, 28.

A native of Orlando, Florida, Butler-Craig became a McNair Scholar in 2017 while earning a Bachelor of Science degree in aerospace engineering at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University.

Growing up, she was drawn to Mae Jemison, the first Black woman to travel into space. But Ronald McNair’s story resonated deeply as well, a connection that only strengthened as she came to know Carl McNair and the McNair family through the program.

When Butler-Craig secured her first internship at NASA, the McNair Scholars Program provided a stipend that made the opportunity possible.

“And I needed that money — to eat,” she said. “Not only do I identify with this person, but this program is responsible for me being in this field.”

Carl McNair attended Butler-Craig’s graduation at Tech in December, where the doctoral graduate introduced him to family members — some of whom had watched the Challenger launch unfold in 1986.

“To connect him with my family, who lived through that moment, was really beautiful,” she said. “It felt full circle.”

In May, Butler-Craig will begin full-time work at NASA’s Glenn Research Center. She is also preparing to apply for a future astronaut class.

“I’d like to go up as a mission specialist,” she said. “My goal was to make myself as competitive as possible by earning a Ph.D. Being an astronaut was a huge motivation for going to graduate school.”

Earlier this month, Butler-Craig traveled to Kennedy Space Center to witness preparations for the Artemis II launch, a key step in NASA’s planned return to the moon for the first time since the 1960s.

“Challenger represents the worst part of our field — the risks we take to do hard things,” Butler-Craig said, reflecting on the 40th anniversary of Challenger coinciding with the Artemis program. “It reminds us that space isn’t just fun or cool. It’s people at the forefront, risking their lives. It’s a heroic enterprise.”

What continues

Carl and Mary McNair’s home in southwest Atlanta is modest and warm, a space shaped by family life rather than public memory. One of the front rooms has been turned into a makeshift playroom, its floor scattered with toys for their grandchildren.

Ronald McNair is spoken of often, but the space resists becoming a shrine. The walls and shelves are filled instead with photographs of grandchildren and Desiree — the daughter Mary McNair was carrying when she felt her baby kick for the first time on the morning her uncle died.

At one point, Mary McNair, a retired Army lieutenant colonel, comes downstairs carrying a large, neatly arranged scrapbook that traces Ronald McNair’s life and death through photographs and carefully clipped news articles. She sets it down gently and turns the pages in silence.

Only when prompted does Carl McNair retrieve items from storage.

First comes a large collage of photographs showing Ronald McNair alongside other Black astronauts.

Then an even larger image of Ronald McNair standing with his classmates Guion Bluford and Frederick Gregory in their spacesuits — the same photograph that once appeared on the cover of Jet magazine, marking a breakthrough moment in American spaceflight.

Finally, Carl retrieves two of his brother’s flight suits. One is a light blue jacket and trousers worn in space. The other is a navy-blue training jumpsuit with a broken zipper.

They are not displayed; they are preserved.

Throughout January and February, the McNairs crisscross the country attending events and galas honoring Ronald McNair and the other astronauts lost aboard Challenger.

Carl McNair also hopes to produce a full-length documentary or feature film — another effort to widen the lens through which Ronald McNair is remembered.

In 2005, Carl McNair wrote his brother’s biography, “In the Spirit of Ronald E. McNair: Astronaut, An American Hero.”

Seven years later, he narrated the NPR StoryCorps animated short “Eyes on the Stars,” which recounts Ronald McNair’s 1959 confrontation with segregation at the Lake City public library.

That building — once a site of exclusion — is now called the Ronald McNair Life History Center Library.

The last mission

For Carl McNair, these acts of remembrance are about ensuring the distance his brother traveled — at home and in space — is fully understood.

“Ronald has one of the most inspirational stories that anyone has ever heard, coming from where we came from in segregated South Carolina — a town of about 2,000 people where most folks worked in the fields picking cotton, beans, tobacco,” he said.

That sense of obligation sharpens each January, when anniversaries collapse time and grief returns on schedule.

“January never stopped being hard. If I can get through January without falling apart, I’m good,” Carl McNair said. “But my job is not to allow his story to be a footnote lost in history. Nothing outside my family has been more important than making sure his legacy continued.”

In that work, the mission continues.