As Delta’s first Black flight attendants, they were ready for social change

The new terminal building at Atlanta Municipal Airport was buzzing with activity in the late 1960s. The jet age had arrived, and in 1961, the $21 million facility became the largest single terminal in the country, designed to accommodate 6 million passengers each year.

Phenola Culbreath, a stewardess for Delta Air Lines, hurried through the concourse to catch her outgoing flight. She had only been on the job for a few months, and she knew the importance of being on time and professional.

As she approached Dobbs House restaurant, she turned to her left and saw a beautiful Black woman wearing the same uniform: a French blue crepe wool jacket with three-quarter length sleeves, a white blouse, pencil skirt and a “Delberet” hat with the Delta emblem on the side.

“My mouth just fell open,” Culbreath said. “She was tall, she was regal, she was elegant … the ideal flight attendant.”

Patricia Grace Murphy had been hired just three months before Culbreath, becoming the first Black woman to serve as a Delta stewardess.

Culbreath recognized her immediately and approached her with excitement.

“She came up and introduced herself,” Murphy said. “I was so happy to see her. I thought, another colored flight attendant? This is good.”

Their first meeting was quick, but they chatted about the highs and lows on the job. C.E. Woolman, principal founder and first CEO of Delta, had died before Culbreath graduated, and Murphy shared stories of his kindness to the stewardesses who would congregate in his office.

Then, having struck up a friendship that has now spanned six decades, they went their separate ways.

Murphy and Culbreath watched the many changes that would take place in the world of aviation from the highs of the jet age when they began their careers to the lows of 2001. After more than 30 years of flying, when 9/11 forever changed the spirit of air travel, they both retired.

Neither of the women would have thought growing up that their lives would be filled with the kind of adventure their careers afforded them or that they would become a celebrated part of Delta’s history, an important part of Black history in America and a symbol of Black achievement for future generations.

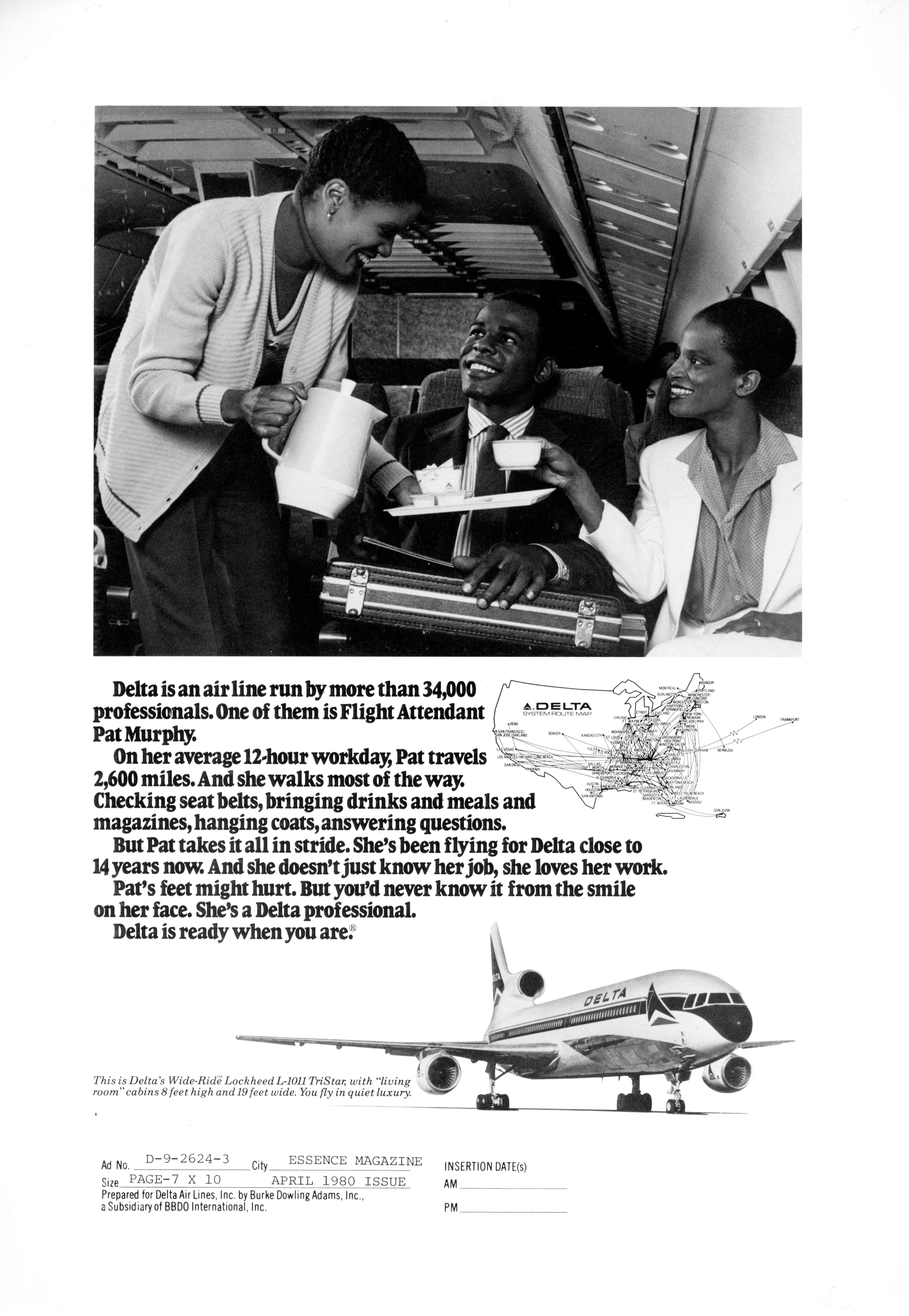

They have been featured in Black newspapers and magazines and in the Delta Flight Museum, and portraits of Murphy are on view in the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

“You are living it, so you are not observing it from the perspective of what it really means,” Culbreath said.

Whenever her friends introduced her as the first Black flight attendant hired by Delta in the South, she would feel embarrassed.

“I didn’t want people to think that I thought I was all that, but now I see it from a different point of view,” Culbreath said. “It was important what happened because things were beginning to open up to Black people and other minorities. I realize now, I was a part of history, of major history, being made.”

Murphy said at the time she was hired, she was mostly happy that she graduated from training. She was also a little scared.

“My mother said there is a plan for you,” Murphy said. “So, I was also excited, thinking, ‘This is going to work.’”

Murphy grew up on Chicago’s South Side with her two brothers, raised by a village that included her parents, extended family and friends. Weekends meant block parties, bike riding and jumping rope in neighborhood streets where everyone looked after everyone else, she said.

As a teen in the 1960s, Murphy attended Chicago’s Woodrow Wilson Junior College. She didn’t know what she wanted to do, but she wasn’t interested in traditional careers then available to young girls: secretarial work, teaching and nursing.

One of her friends saw a newspaper ad for airline schools, and Murphy jumped at the opportunity. At the end of the monthlong training course in Kansas City, Missouri, recruiters came to fill jobs for reservationists and stewardesses.

Murphy applied to several airlines. She admired the Emilio Pucci-designed uniforms of Braniff International Airways and wanted to work there, but Delta gave her the only “yes.” And the recruiters didn’t want her to take reservations; they wanted her to be a stewardess.

Only after she accepted the job did Delta officials tell her that she was the first “colored” girl to be hired for that role.

“That was a shock,” Murphy said. “I had no idea I was the only Black girl that was hired.” They recommended she be based in Chicago or Atlanta. She chose the Windy City.

For one of her earliest flights, she was scheduled to fly on a Convair 440, a small passenger propeller plane, as the only flight attendant.

“I am on there with all these beautiful people, and I am the only Black girl on there serving them, and I am flying to the South,” Murphy said. She was concerned, as were her supervisors, who, Murphy recalled, replaced her with another flight attendant.

While Murphy was embarking on her new career, Culbreath was looking for a way out of a boring job as a long-distance phone operator. She had attended Clark Atlanta and Georgia State universities but hadn’t settled on a profession.

A Grady baby, Culbreath grew up in the neighborhoods of south Atlanta. Her father was a deacon at St. Stephen Missionary Baptist Church, where Culbreath built the spiritual foundation that would guide her life. Her mother was a homemaker with a gift for taking care of others, a trait that Culbreath embraced as she matured.

“Wherever we lived in different communities, there would be young mothers, sometimes single parents, with little children to raise, and my mom was always there for them,” Culbreath said.

She babysat for a neighbor who was the first Black ticket agent for Delta, and Culbreath asked her how she got the job. The neighbor made the connection, and Culbreath got interviews. “I had two interviews, and I was hired (as a stewardess),” Culbreath said. “I thought, well, this is going to be amazing.”

Her first flight was on a turnaround to Chattanooga on a DC-6, Delta’s first aircraft with tray tables and air-conditioning. Culbreath rode as a passenger while observing the other flight attendants at work. For six months, she was based in Memphis before returning to the hub in Atlanta.

Air travel midcentury was glamorous, and flight attendants were part of the allure. Attractiveness ran through their ranks, and many were selected to model in advertising for the airline. They wore stylish uniforms complete with matching bags, hats and gloves.

But Delta also had strict requirements: no marriages, no pregnancies and no one more than 120 pounds. They were expected to always be pleasant and of service to customers, even when customers treated them poorly.

Murphy knew that, as Delta’s first Black flight attendant, all eyes were on her. She felt that her success was a success for any Black flight attendant who came after her. But sometimes, no matter her professionalism, some people didn’t respond well to her presence.

On one flight, as she attempted to serve a passenger and his wife, he said, “Don’t you know your place?”

The cabin grew quiet. “This is my place,” Murphy said.

She was disappointed and disgusted. “I could look in their faces and see they knew they were wrong,” Murphy said, “but they didn’t want to apologize.”

Culbreath, too, encountered people who were not kind. “I did not let that affect me. I left it at the office and didn’t take it home with me,” she said.

Both women relied on their faith to help them through the tougher moments. And they embraced the people who gave them a safe haven.

Culbreath recalled one such moment in the book “Stars in the Skies” by Casey Grant, a Black Delta flight attendant who was hired in 1971. Once during a layover in Jackson, Mississippi, a city still deeply entrenched in racial conflict, the captain of Culbreath’s flight asked the hotel clerk to give her a room on the same floor so that if she had any problems, he would be able to assist.

As more Black people turned to air travel, Culbreath and Murphy experienced moments of recognition and joy with passengers who were happy to see their faces. “They let the pride of the moment show, and they shared that with me,” Culbreath said.

Life as a flight attendant was exciting for Murphy and Culbreath. The country was changing, and they had a front-row seat and entry to destinations across the world.

Culbreath loved traveling to San Francisco, riding the cable cars and shopping at Nordstrom and I. Magnin & Co., stores that hadn’t yet made it to Atlanta. She and fellow stewardesses would stop at a floral shop in the city and bring fresh flowers back home. They also hauled Coors beer back to Atlanta from out west. “Everyone loved when we would land,” she said with a laugh.

Murphy recounted her trips to the Caribbean and a favorite route from New Orleans to Caracas, Venezuela.

They were living the lives they wanted to live, seeing the world, meeting interesting people.

Within a few years after they were hired, classes of Delta flight attendants had more Black members. By 1971, there were four Black women in the graduating class.

For more than three decades, Murphy and Culbreath weathered the ups and downs of the aviation industry, and mostly, they loved it. Then, in 2001, 9/11 changed everything.

Air travel suddenly seemed perilous, especially to those for whom it was a career. Civilian flights were grounded for several days, passengers became security risks, and even frequent flyers felt some level of anxiety. The world was volatile and rapidly changing.

Murphy said 9/11 left her feeling as if she were in a daze.

“It was horrible,” she said. When Delta offered early retirement, she took it. “I was ready to leave. I retired at 55 after exactly 35 years,” Murphy said.

A few months later, Culbreath also retired, after renewing the real estate license she had first earned in 1978. “I only had 36 years,” she said. “I wasn’t really ready to give it up because I had a dream job.”

Murphy resides in Florida, where she has done community service and volunteer work. Culbreath stays active in her Atlanta community, volunteering with a group that supports a new school in South Fulton.

Murphy and Culbreath never had the opportunity to work a flight together, but for 60 years, they have been bonded by a sense of duty to inspire their people and their communities.

“I am so grateful and thankful because I have seen our people come such a long way and make so many strides and progress,” Culbreath said. “We have got to keep the story going, we have to keep history right in your face. We can’t afford to let people forget what happened before these things opened up to us.”

For her part, Murphy believes young people should stand on their beliefs and stay strong in focusing on their dreams.

“Continue to go forward, don’t look left or right. Any negative, try to overcome it, but don’t bury your head in the sand,” she said. “Just believe in your heart that whatever you want to do in your life, you can pray on it and go forward.”