At 100, Mozel Spriggs’ life tells the story of Black dance in Atlanta

In 1959, Mozel Spriggs and her husband, Alfred, purchased tickets to see dancer Alvin Ailey at Atlanta Civic Center, the year after he founded the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater to celebrate Black history and culture through dance.

Spriggs joined Morris Brown College two years earlier and offered dance in her physical education classes at the historically Black college. They moved to Atlanta in 1955 after her husband became Clark College’s (now Clark Atlanta University) chemistry department chair.

The couple was shocked when they arrived at the Civic Center and found fewer than 100 people attended.

“I thought it was going to be crowded. I was so disappointed that people — Black or white — did not know enough about modern dance. I felt if I could interest the community in dance beyond ballet, it would influence them to learn about it and be interested to come out,” Spriggs said.

She knew dance was a catalyst that could educate diverse communities on various styles of performance art, build their confidence and have health benefits.

Four years later, Spriggs left Morris Brown to join neighboring Spelman College to create its dance program under the physical education department.

Spriggs, who turned 100 years old on Jan. 1, was offered the position at the all-female college by the department chair, who attended their alma mater, Hampton Institute (now Hampton University).

“She knew that I danced at Hampton and told me I needed to come over to Spelman and start the dance program over there,” Spriggs said.

Spriggs made classes practical and interactive. Before starting her workday, she swam 30 laps every morning.

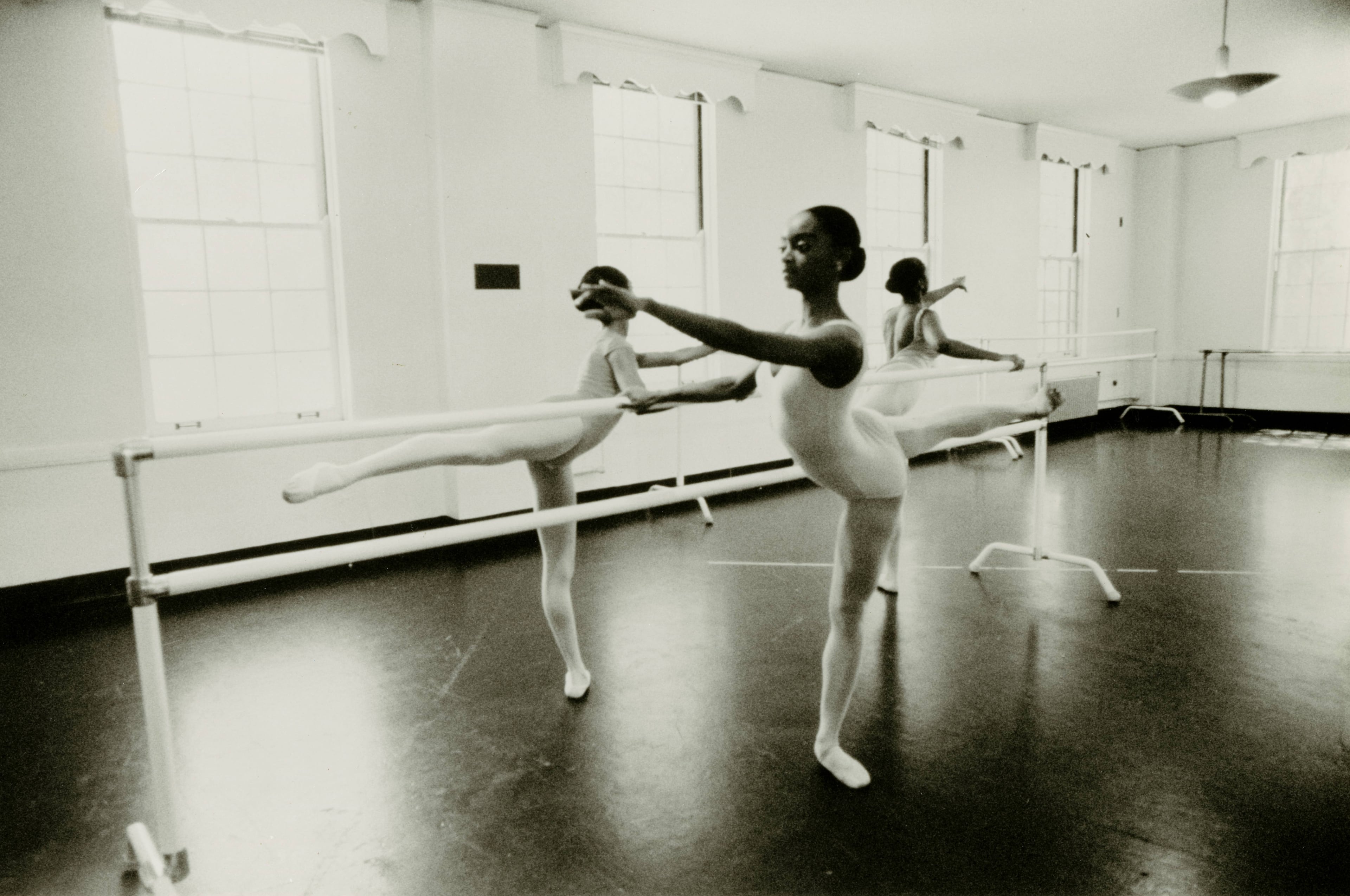

Spriggs, who specialized in modern dance, led rehearsals in Spelman’s dance studio and stretched with her students. “I’m a hands-on person. I showed them what I wanted them to do and did warm-ups with them. I could look in front of the mirror and see what everybody was doing,” Spriggs said.

Spriggs also regularly invited professional dancers and dance ensembles across genres to meet and guide students. She was awarded grants to create weekend and monthlong residencies to host dancers and choreographers Ailey, Katherine Dunham, Arthur Mitchell, Rod Rogers and Pearl Primus to lead workshops, lectures and master classes each semester.

She made the classes open to residents and aspiring talent.

“I could bring in as many (performers) as I wanted to bring in. I set it up with the president to invite them at various times, allow them a place to stay on campus in the guesthouse and eat in the dining hall,” Spriggs said.

“I invited dancers and companies around and outside of Atlanta to come and participate in those, and everybody I asked was happy to come.”

Spriggs’ goal — whether participants were formally trained or not — was for students to try and develop an appreciation for dance.

“Many of the students had never even danced before, but I expected them to do the best that they could, learn enough and love it. I knew they couldn’t do everything well, but I was always on them about their feet and to move properly,” she said.

In 1986, Spriggs became chair of the Division of Fine Arts. She spent a semester teaching dance in the Ivory Coast the following year.

Spriggs retired from Spelman in 1991 after 27 years of service. “I was tired and just ready to go,” she said.

Spriggs dedicated her time consulting aspiring dance companies. In 1990, she assisted with developing Ballethnic Dance Company, a Black-owned classical ballet ensemble in East Point.

She gave founders and couple Waverly Lucas and Nena Gilreath rehearsal space for the company, teaching jobs at Spelman, professional dancers to teach their company, and formed their board of directors.

Gilreath said Spriggs was supportive and resourceful.

“She had contacts in every place, found the creator of our first logo and got her assistant to organize information because we had no clue about foundation and paperwork. She introduced us to Judith Jamison, who gave us our first letter of recommendation as a dance company so that people would take us seriously,” Gilreath said.

Spriggs remained active. In January 1992, she started teaching free weekly exercise and dance classes at her church, Radcliffe Presbyterian Church. She did it for two decades.

Spriggs also took up square dancing and began offering adult water aerobics classes at her home.

Spriggs said participating in physical activities postretirement was therapeutic and kept her passionate about dance.

“I did what I did because that’s what I love and enjoyed every moment of it. I didn’t even think about things or let them worry me,” Spriggs said.

Spriggs is being honored at the International Association of Blacks in Dance’s 36th annual conference gala at Hyatt Regency Atlanta on Feb. 7.

She is humbled by the recognition after turning 100 this year. “I feel the same as I did starting out. Getting awards isn’t that important to me, and I wasn’t thinking about a legacy,” Spriggs said.

Gilreath hopes future dancers of color will become aware of Spriggs’ contributions to Atlanta’s dance scene.

“She’s a stellar matriarch of dance in our community that opened doors and gave many of us a platform to grow, lead and provide access for other people. She had to get her flowers right here and now, and younger generations need to know where the root is,” Gilreath said.

Asante Sana: International Association of Blacks in Dance Awards Gala. 5:30 p.m. Saturday, Feb. 7. $150. Hyatt Regency Atlanta, 265 Peachtree Street NE, Atlanta. conference.iabdassociation.org

This year’s AJC Black History Month series marks the 100th anniversary of the national observance of Black history and the 11th year the project has examined the role African Americans played in building Atlanta and shaping American culture. New installments will appear daily throughout February on ajc.com and uatl.com, as well as at ajc.com/news/atlanta-black-history.