Atlanta leaders remember the Jesse Jackson who ‘pushed hope into weary places’

When Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens stepped to the podium Tuesday morning to open a panel on preserving Black history and culture, he planned to stay on script. But the moment would not allow it.

Just hours earlier, he and the rest of the world had learned civil rights leader and political trailblazer Jesse Jackson, a protege of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., who carried the civil rights movement forward through politics and activism, had died at the age of 84.

“So, I want you to repeat after me,” Dickens said, preparing to summon a refrain he grew up hearing. “I am — somebody. I am — somebody.”

The crowd at The Gathering Spot for the “When HIStory Was Watching” program answered in unison.

“I am,” they shouted. “Somebody.”

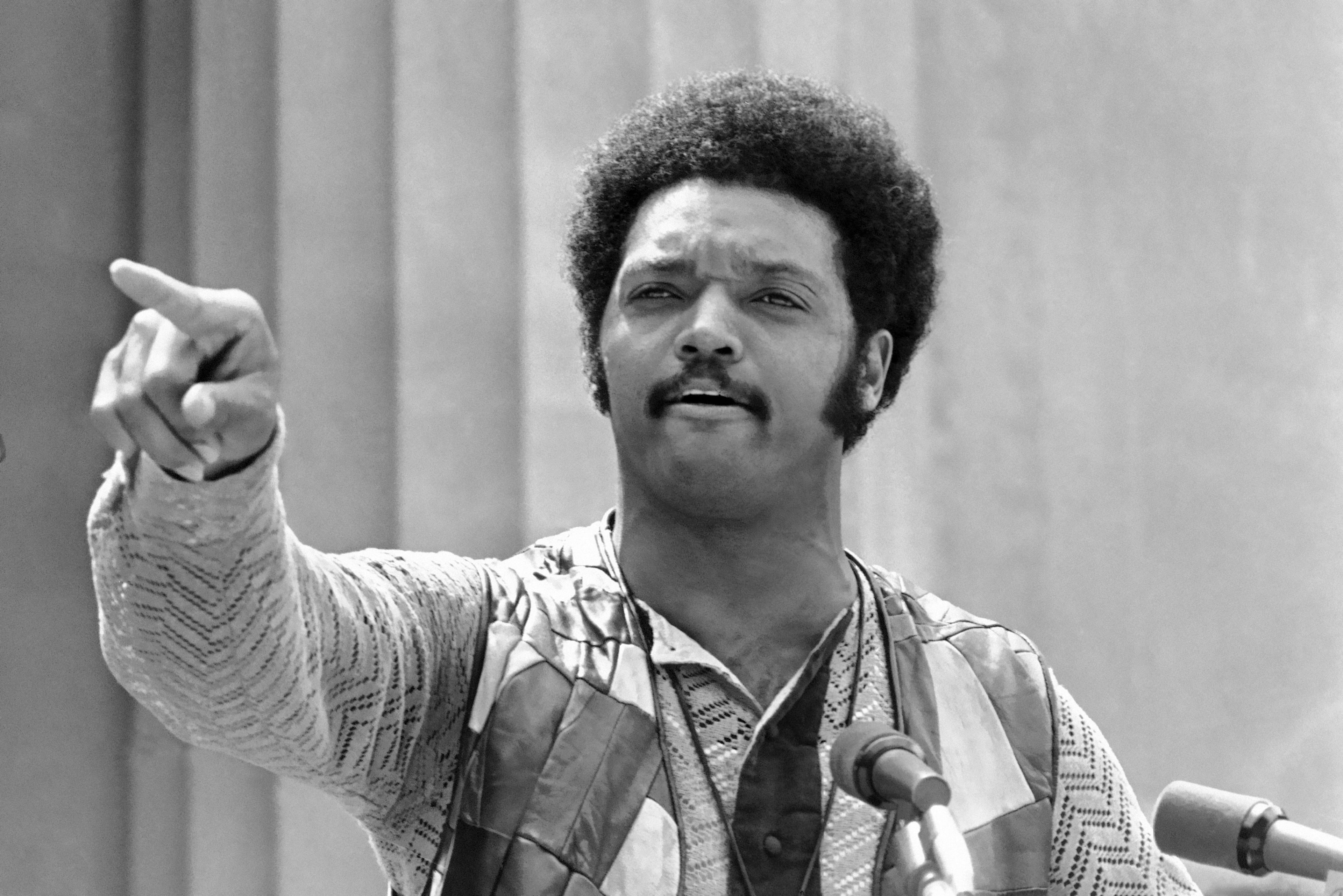

It was the same declaration Jackson had turned into a national mantra, often reciting: “I may be poor, but I am Somebody; I may be young, but I am Somebody; I may be on welfare, but I am Somebody.”

The room held both grief and gratitude. Even as organizers kept the focus on preservation and legacy, Jackson’s death shaped the tone of the morning. His daughter, Santita Jackson, confirmed he died at home in Chicago, surrounded by family after years of battling progressive supranuclear palsy, a rare and severe neurodegenerative condition.

Dickens was joined by four former Atlanta mayors — Bill Campbell, Kasim Reed, Keisha Lance Bottoms and Ambassador Andrew Young — each offering reflections.

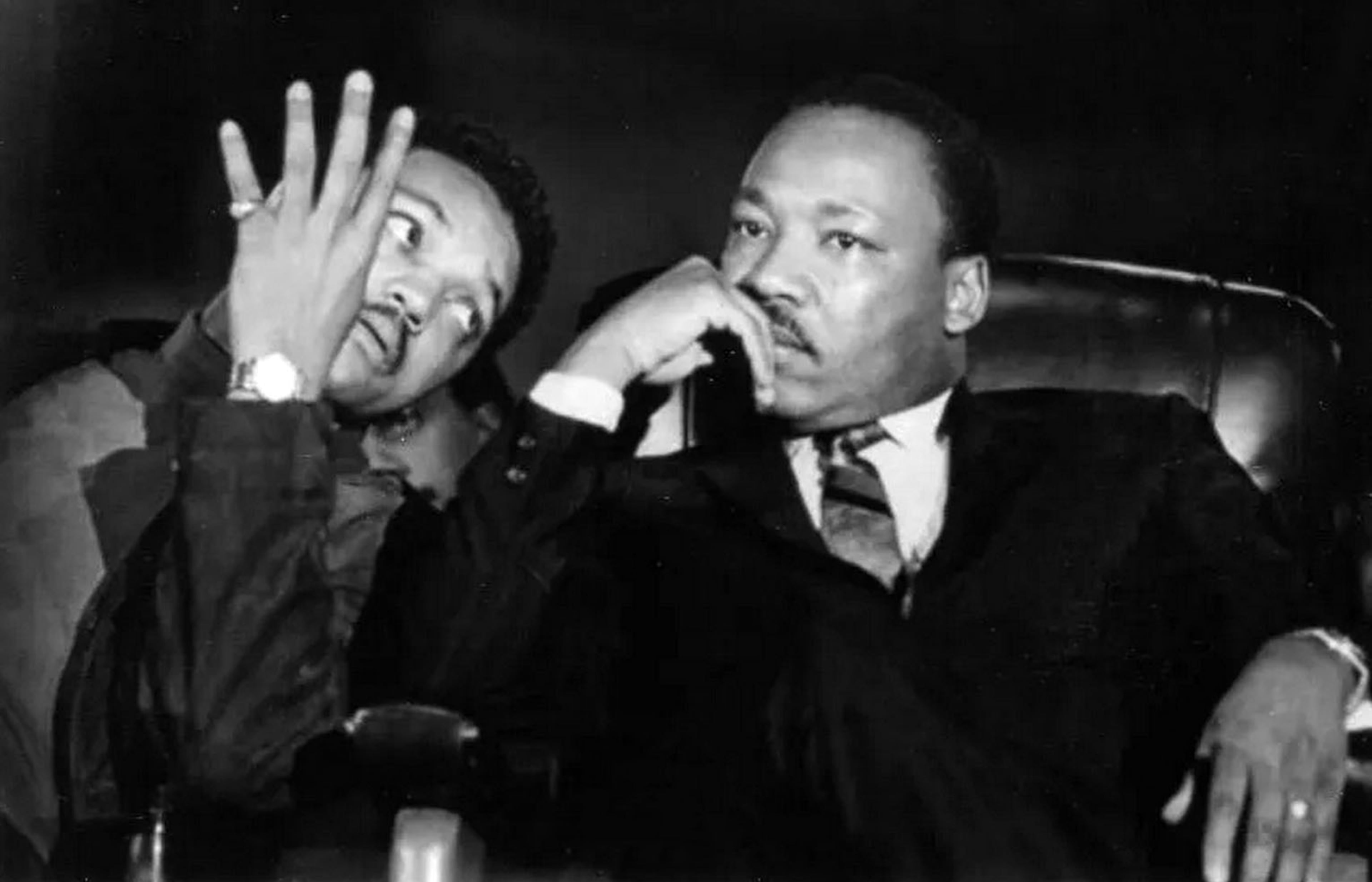

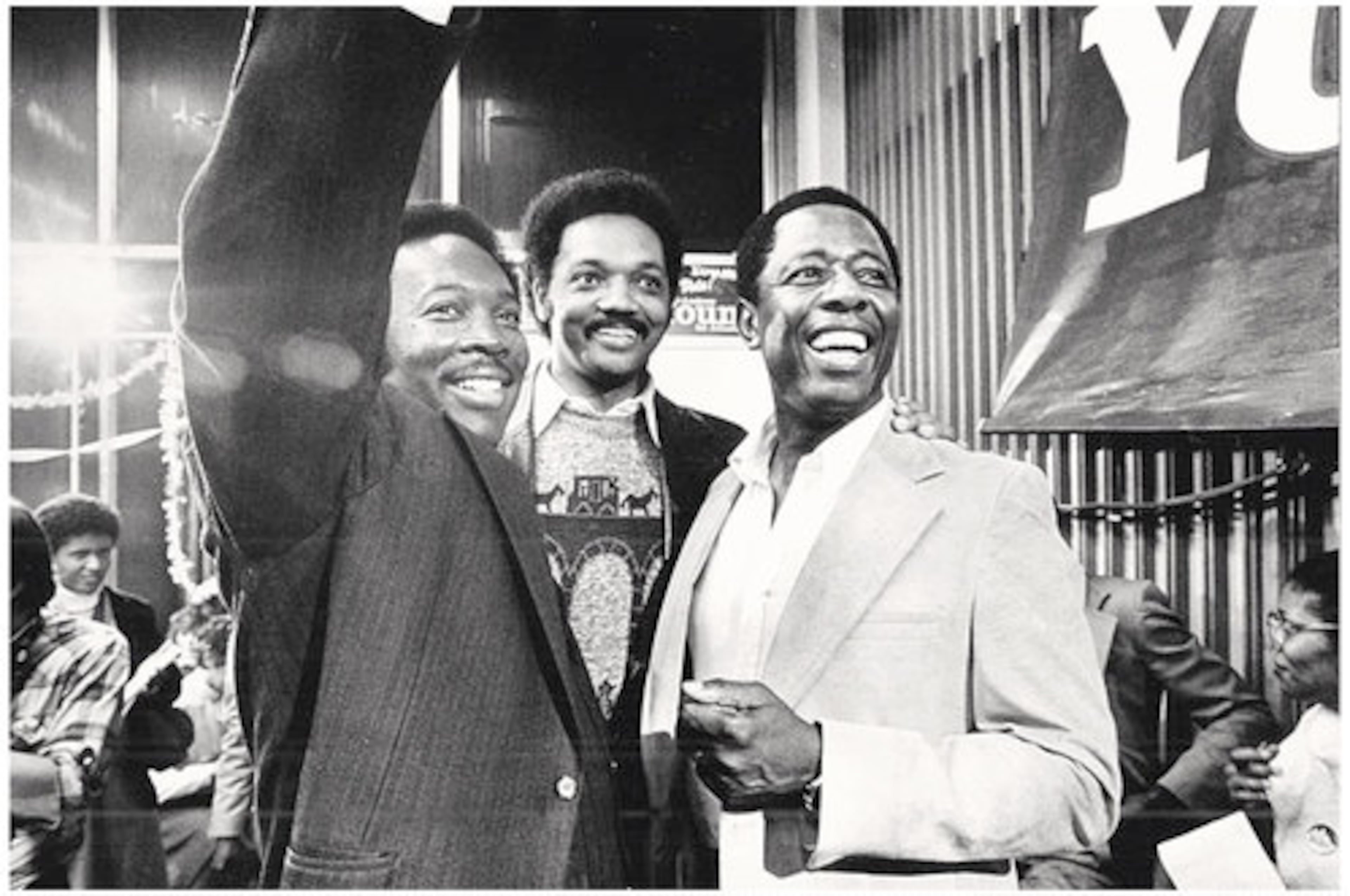

Young, who was originally scheduled to be on the panel to discuss preservation, instead found himself remembering a friend and fellow foot soldier in the movement. He remembered meeting a young Jackson in 1965 in Selma during preparations for the Selma to Montgomery March for civil rights.

A group of marchers had just been beaten, and a weary Young, awake for days, was trying to hold the line. That’s when Jackson approached him.

“This great big, good-looking kid comes up and says, ‘You look exhausted,’” Young said. “I said, ‘I am exhausted.’ And he said, ‘Look, you need to go get some sleep. I can man this barricade.’ I didn’t even ask him any more questions. I said, ‘Help yourself.’ And I left and went to get a nap.”

Young said that was his first introduction to Jackson’s willingness to “step up and be a leader.”

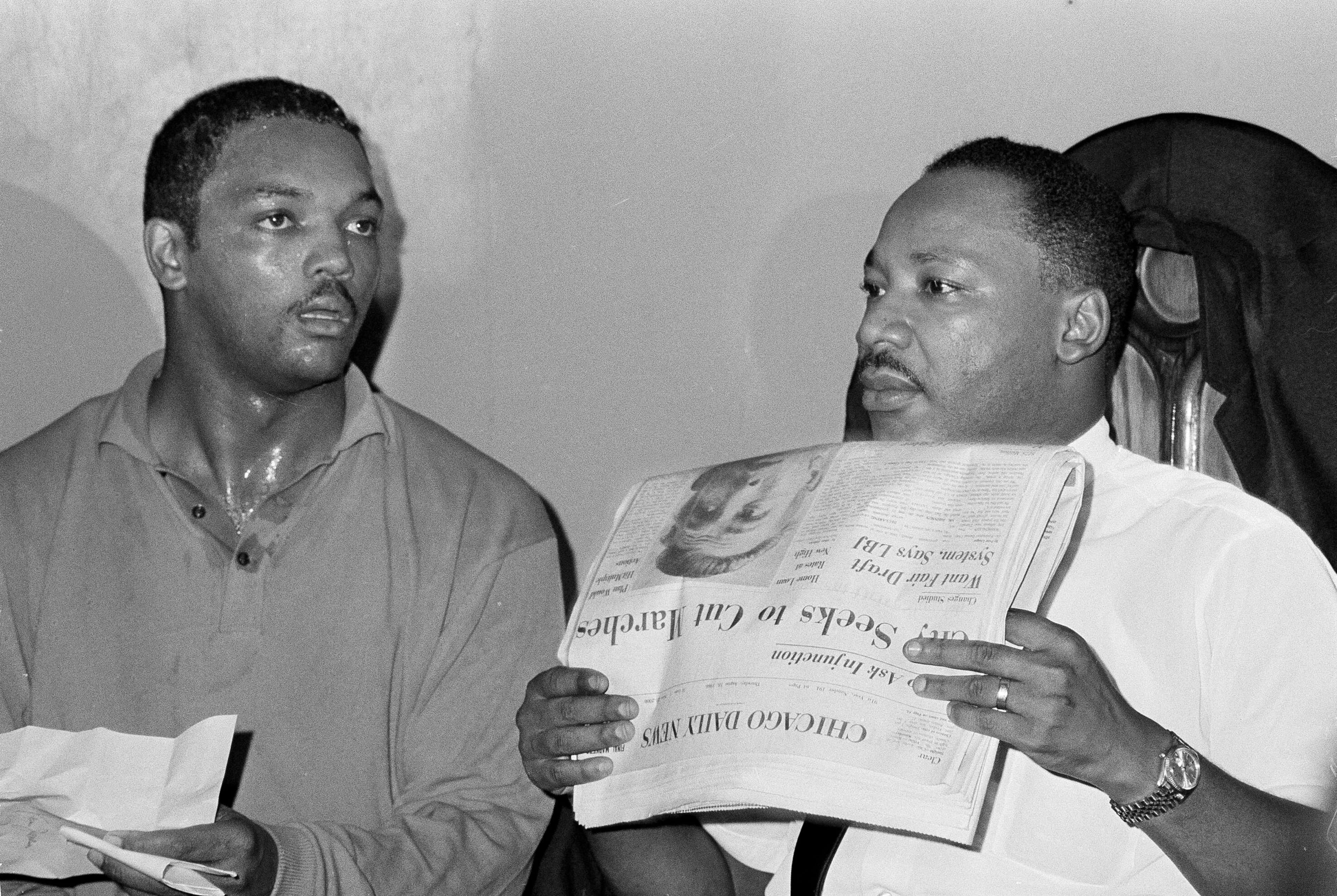

That instinct would define him. By the late 1960s, Jackson had been dispatched by King to Chicago to lead Operation Breadbasket, pressing corporations to hire Black workers and invest in Black communities. After King’s assassination at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis in 1968, Jackson emerged as one of the most visible heirs to the movement’s moral urgency.

“He made a tremendous contribution to this country and to the world,” Young said.

Throughout the day, tributes poured in from civil rights leaders and elected officials across the country, underscoring the breadth of that contribution.

Sen. Raphael Warnock, who serves as senior pastor at Ebenezer Baptist Church, said Jackson’s moral force resonated in both faith and public life.

“He gave me a glimpse of what is possible and taught me to say ‘I am somebody,’” Warnock said, recalling Jackson’s influence on his own journey from the pulpit to the Senate. “He made me possible through the work that he did all of those decades ago.”

Warnock said Jackson’s example feels especially urgent in the current political moment, with ongoing battles over election access and voting rights across the country.

The two men shared meals at Paschal’s, the historic crossroads of Atlanta’s civil rights movement, and in Warnock’s first year as pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church, he invited Jackson to preach. During that visit, Jackson raised concerns about Hurricane Katrina evacuees in Atlanta who feared their votes would be disenfranchised because they were required to vote in person in Louisiana.

Warnock responded by organizing buses to New Orleans.

“It was Jesse Jackson who sparked in me that concern,” said Warnock, adding that the moment sharpened his focus on voting rights while helping to shape his political agenda. “Pointed it out.”

For Bottoms, the Democratic Party’s gubernatorial early front-runner, those moments carried her back decades.

“For people of my age, born after the Civil Rights Movement, it was really the first opportunity that you saw a Black man stand on the national stage and speak with such power and authority and conviction and pride,” said Bottoms, adding that when she worked in the White House, Jackson would call the Oval Office’s switchboard looking for her when she didn’t return his messages fast enough. “I just remember being mesmerized.”

Dickens also framed that contribution in generational terms, saying Jackson spoke “truth to power.”

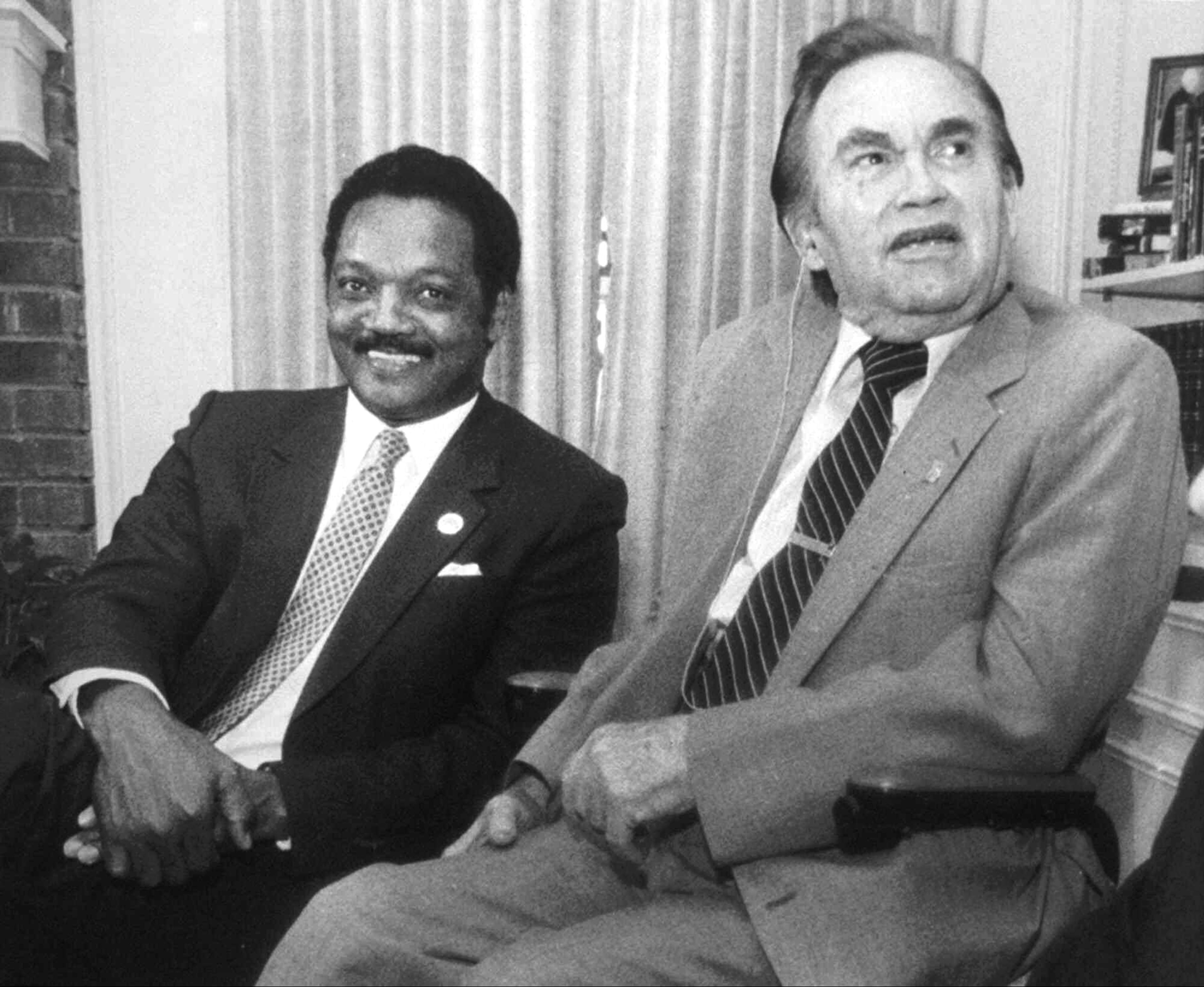

Dickens grew up in an era when Jackson was a towering figure, known as much for politics — he ran for president twice in the 1980s — as for civil rights.

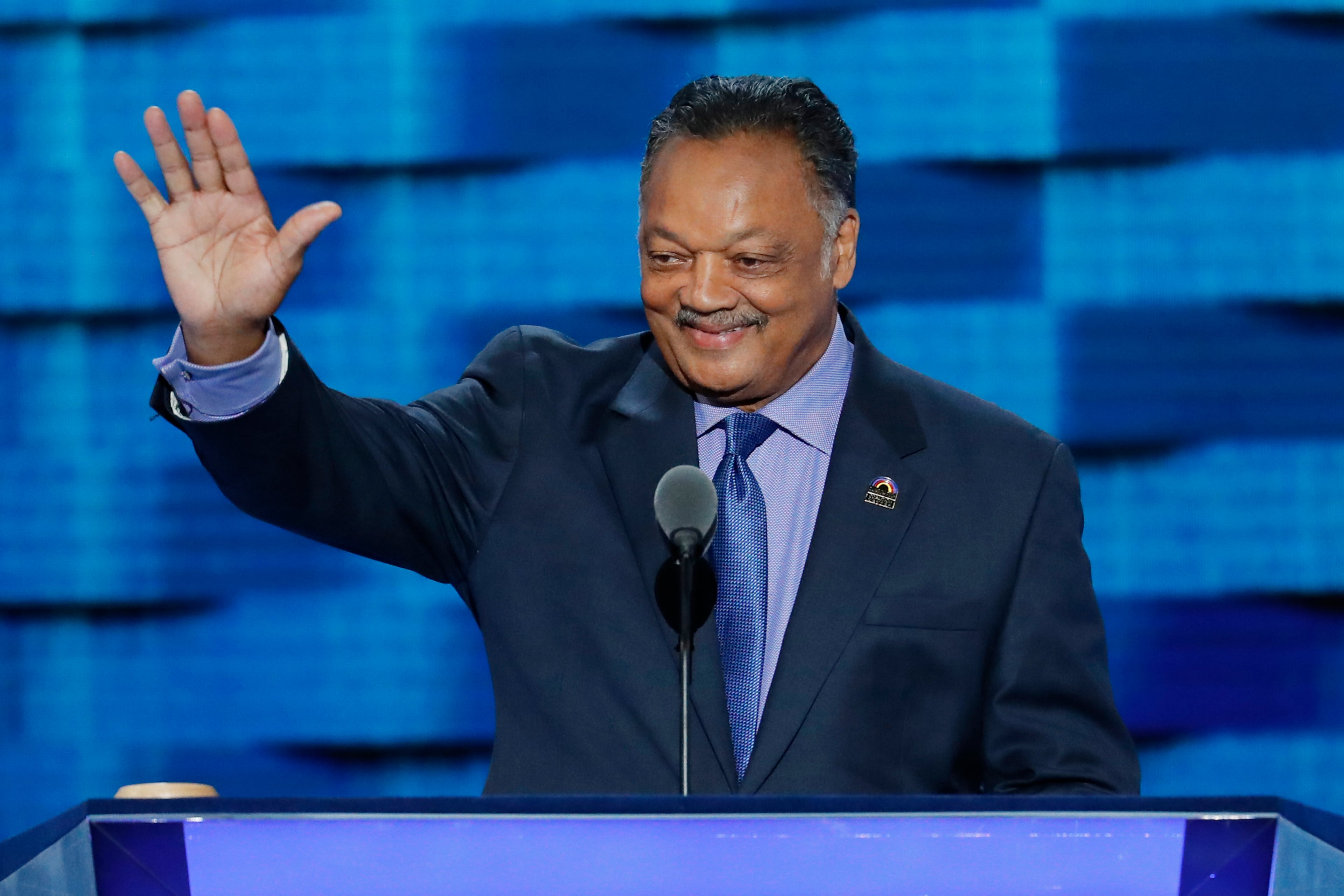

In 1988, Jackson won 13 Democratic primaries and caucuses, the strongest showing by a Black presidential candidate before Barack Obama, urging supporters to “Keep hope alive.”

“I remember as a kid over and over again quoting, ‘I am somebody.’ No matter what economic station you’re in, what social station you’re in, you felt what Jesse Jackson was saying was, ‘I am somebody. I matter,’” Dickens said.

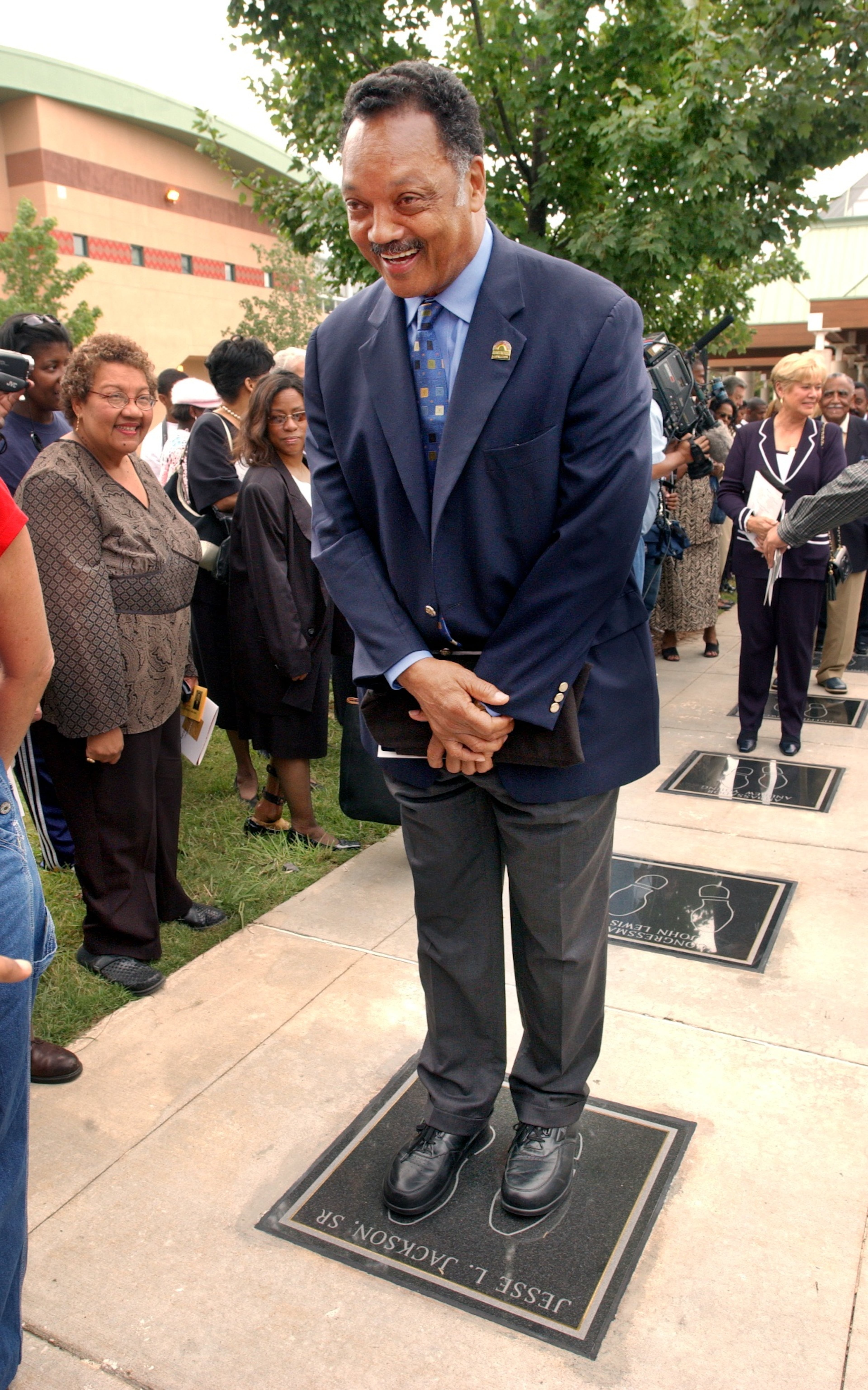

Through Operation PUSH and later the Rainbow/PUSH Coalition, Jackson translated protest into policy pressure, pushing for voting rights, job access, education and health care, and demanding corporate accountability.

Campbell reflected on Jackson’s moral force, calling him a “freedom fighter.”

“At his heart, he always wanted people to find equality, and he fought for that all the way through the bitter end,” Campbell said. “His passing is a great loss for our nation and for the world.”

Not only was Jackson involved in civil rights marches and electoral politics, but he also understood the power of economic leverage — particularly the building and growth of minority — and women-owned businesses.

Former Atlanta Mayor Shirley Franklin, who met Jackson in the early 1970s in Washington, D.C., and followed his career closely — including his involvement in Maynard Jackson’s historic mayoral election — said economic inclusion was one of Jackson’s defining commitments.

“One of the things that is a highlight for me is his real understanding of the importance of minority and female business,” said Franklin, adding that Jackson was the guest preacher at her son’s christening in 1974. “He never gave up hope, and he was always optimistic. He had a good sense of humor, he was a good strategist, and he was inclusive in his vision of America.”

Bernice King, daughter of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., echoed that sentiment, calling Jackson a lifelong champion of the marginalized who “pushed hope into weary places.”

She praised his work through Operation PUSH and the Rainbow Coalition to widen opportunity and build bridges across race and class.

“He was a gifted negotiator and a courageous bridge-builder, serving humanity by bringing calm into tense rooms and creating pathways where none existed. As we grieve …, we give thanks for a life that pushed hope into weary places. We honor his legacy by widening opportunity, uplifting the vulnerable, and building the Beloved Community.”

That work extended beyond U.S. borders. Jackson helped negotiate the release of American hostages abroad and, in 2000, was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Bill Clinton.

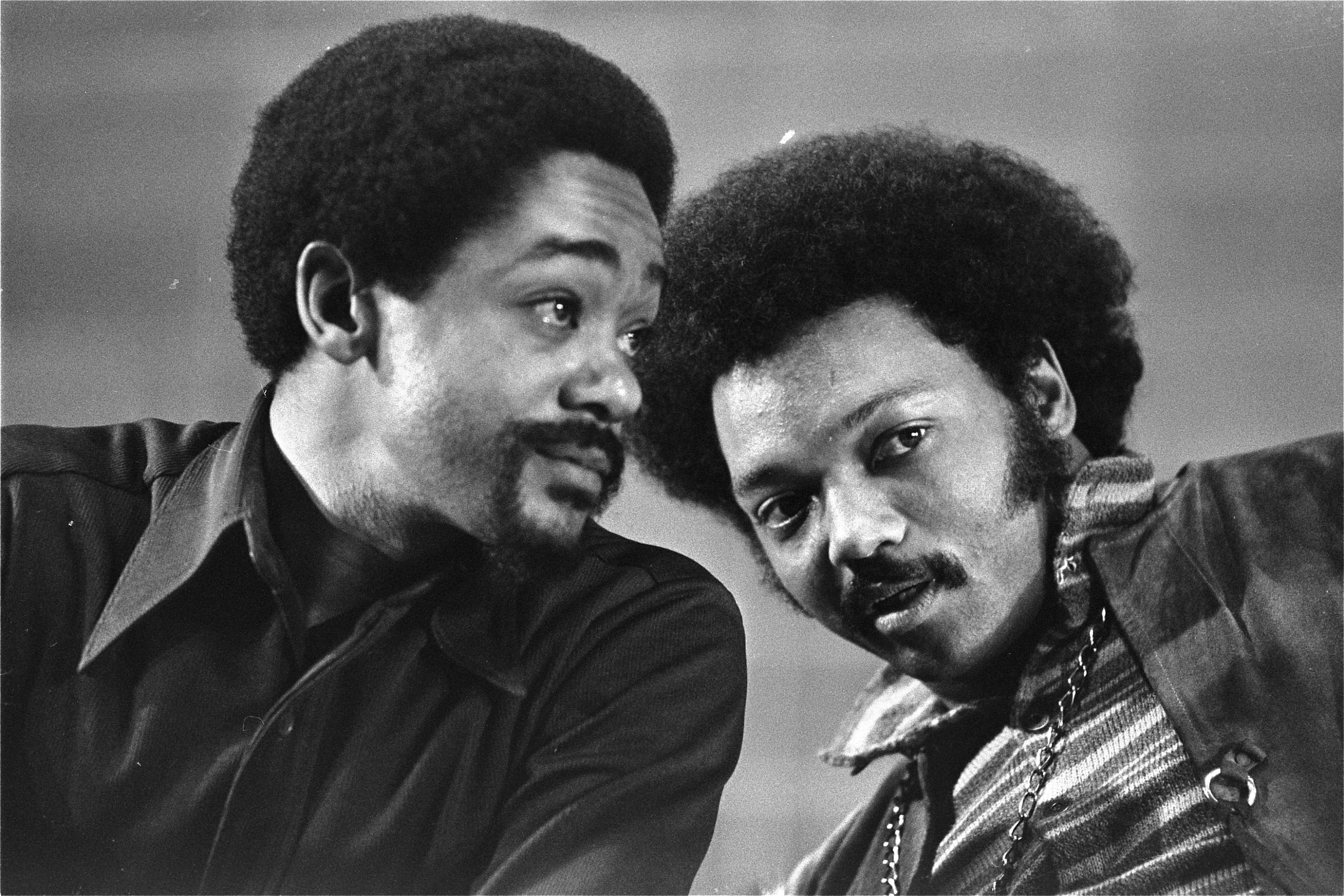

For Reed, the loss was deeply personal. He said the opportunities he has had as a lawyer and politician were possible because Jackson was what he called a “frontliner.”

Reed described the many private calls and prayers from Jackson.

He reflected on a phrase Jackson would whisper to him: “If you ever fall down, get up, because the ground is no place for a champion.”

Reed paused. “That’s where my heart is today.”

Even in his later years, as illness slowed his speech and movement, Jackson continued appearing at protests — from Minneapolis during the George Floyd demonstrations to courtrooms in Georgia during the Ahmaud Arbery trial — insisting that America confront what he once called its “unfinished business.”

That is why the Rev. Al Sharpton, who considered Jackson his mentor, called him a “consequential and transformative leader who changed this nation and the world.”

“He shaped public policy and changed laws,” Sharpton said in a social media post on X. “He kept the dream alive and taught young children from broken homes, like me, that we don’t have broken spirits.”