Black history at 100: Five years that changed Atlanta

In 1929 — at least for Black Atlantans — Atlanta sat at a crossroads.

It was a place of opportunity, tightly fenced by segregation. Black residents built schools, businesses, churches and neighborhoods even as Jim Crow laws dictated where they could live, learn, work and vote. Atlanta was, at once, one of the most promising Black cities in the country and one of the most rigidly controlled.

The slogan “the city too busy to hate” had not yet entered the civic lexicon, but the logic behind it was already visible. White leaders favored economic order over racial terror.

Not equality, but segregation instead of the mob violence seen elsewhere in the South. For Black Atlantans, that uneasy balance created narrow but vital space to build institutions of their own.

That tension — between possibility and constraint — is central to understanding Black history, said Karsonya Wise Whitehead, president of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History.

“Black history is not just about struggle,” Whitehead said. “It’s also about building, about agency, about achievement.”

Nowhere was that clearer than along Auburn Avenue. By 1929, the street — often described as the “Richest Negro Street in America” — was lined with Black-owned banks, insurance companies and funeral homes, sustaining a growing Black middle class of teachers, ministers, doctors and entrepreneurs rooted in stable neighborhoods and social networks.

By the late 1920s, Atlanta had become the premier center of Black higher learning, anchored by Atlanta University, Clark College, Morehouse College, Spelman College and Morris Brown College.

These schools trained ministers, teachers and professionals, emphasizing race pride, discipline and a clear understanding of racism. Even underfunded Black public schools were staffed by educators who believed they were, quite literally, “training the race.”

It was into this world that Martin Luther King Jr. was born on Jan. 15, 1929 — three years after Carter G. Woodson launched Negro History Week.

Woodson, a historian and educator, was the second African American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard University after W.E.B. Du Bois. The son of formerly enslaved parents, Woodson believed historical erasure carried lasting psychological and civic consequences.

“Those who have no record of what their forebears have accomplished lose the inspiration which comes from the teaching of biography and history,” Woodson wrote in 1933 in his book “The Mis-Education of the Negro.”

Woodson’s project was an attempt to document Black achievement and correct a national narrative that had ignored it.

The observance was not created simply to remember the past, but to insist that Black excellence, intellect and contributions were understood as foundational to the American story.

“He said we need to set a week aside so that Black families could spend time teaching Black children about who they are and where they come from,” Whitehead said. “Our lives didn’t start and end with American slavery. We’re more than just a footnote in the American historical narrative.”

When Woodson introduced Negro History Week, Jim Crow was entrenched after the collapse of Reconstruction.

Woodson selected the week that included the birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln, dates already recognized in Black communities and symbolically tied, in his view, to African American freedom and citizenship.

Whitehead pointed to Black soldiers in the Revolutionary War and the political gains of Reconstruction, including the election of more than 600 Black men to public office after the passage of the 15th Amendment in 1870, which gave Black men the right to vote.

“There was an amazing contribution to American history,” she said. “And that’s what he wanted us to teach about, because there was a sense that all we had done was slavery.”

For decades, Negro History Week was embraced by educators and civic groups, taking on new urgency during the Civil Rights Movement.

The observance grew organically, first expanding from Negro History Week into Black History Month through the work of educators and civic groups.

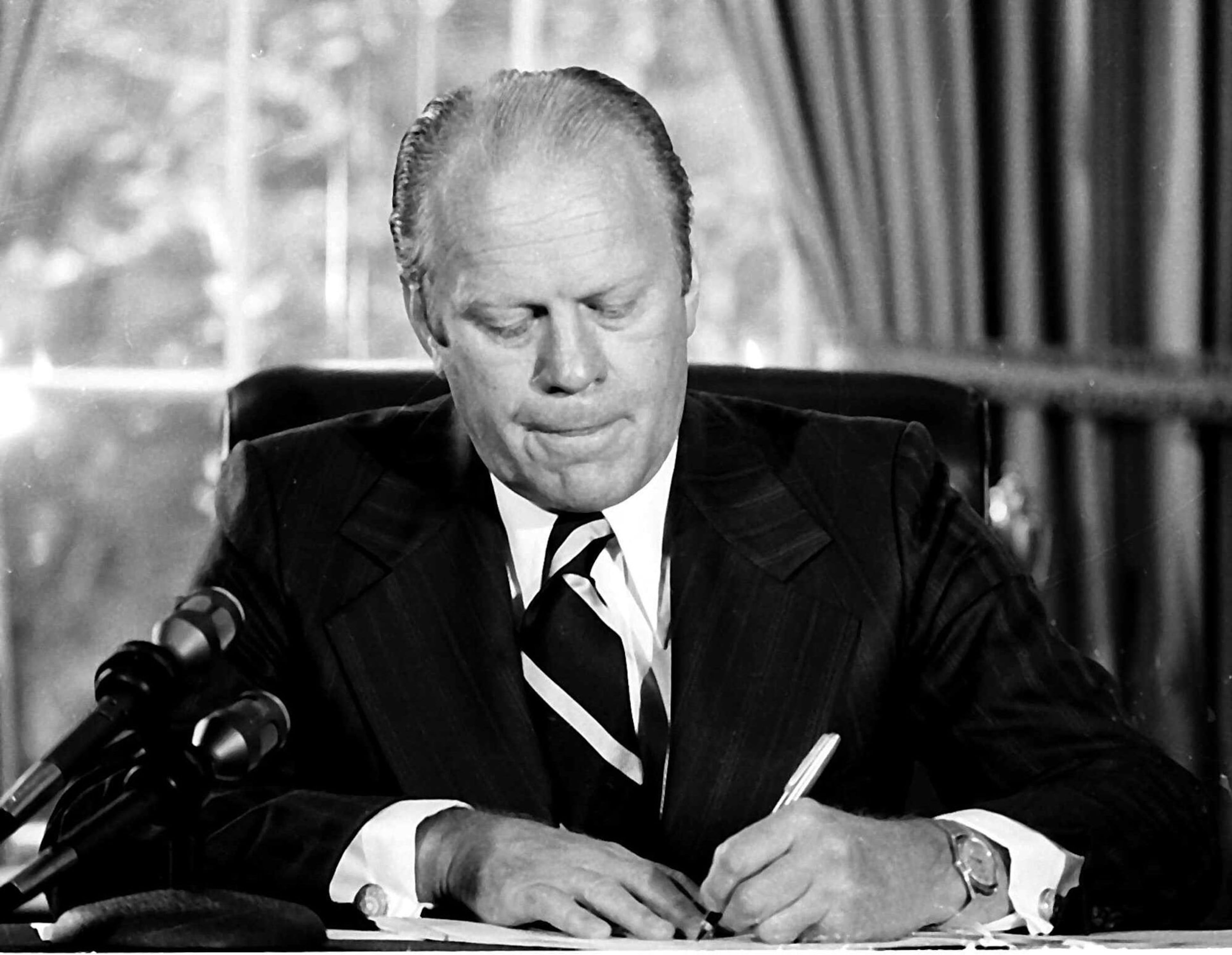

It received formal recognition in 1976, when President Gerald Ford, during the nation’s bicentennial, issued a White House proclamation calling on Americans to recognize the contributions of Black Americans to the nation’s history.

Whitehead said that sequence is often misunderstood.

“It was something that was selected and chosen by us,” she said. “The proclamation came later.”

In that sense, King was born into a city already practicing the values Woodson was trying to teach the nation — self-determination, institutional strength and moral clarity — even as it lived under the constraints of segregation.

As the nation marks a century since the first formal celebration of Black history in 1926, Whitehead said the anniversary lands in a moment of renewed backlash, as political leaders move to roll back diversity initiatives and narrow how Black history can be taught, remembered and debated.

“There is no American history without Black people,” Whitehead said. “That American history — that narrative, that quilt — includes our contributions.”

In the span of 100 years of Black history commemoration, Atlanta would be tested repeatedly.

Its Black communities would confront barriers, change systems and, at critical moments, redefine the city’s direction.

That arc can be traced through five consequential years when Atlanta’s Black history shifted course and left lasting marks on the city and the nation.

After 1929, the year of King’s birth, those turning points came in 1961, 1968, 1974, 1994 and 2020, showing how Black Atlanta moved from possibility to power, from institution-building to protest and from survival to transformation.

The first of those moments came more than three decades later, when the fight over education forced Atlanta and Georgia to confront who its promise was meant to serve.

1961: School doors open, narrowly

“This is a white man’s college, and you are perfectly powerless to help yourselves.”

Patrick Hues Mell, the chancellor of the University of Georgia from 1878 until 1888, said those words shortly after the Civil War, when a group of Black Georgians asked that their sons be admitted to the state’s flagship institution.

For decades, Mell’s declaration effectively stood as policy.

Nearly a century later, that barrier finally broke through pressure and litigation, not enlightenment.

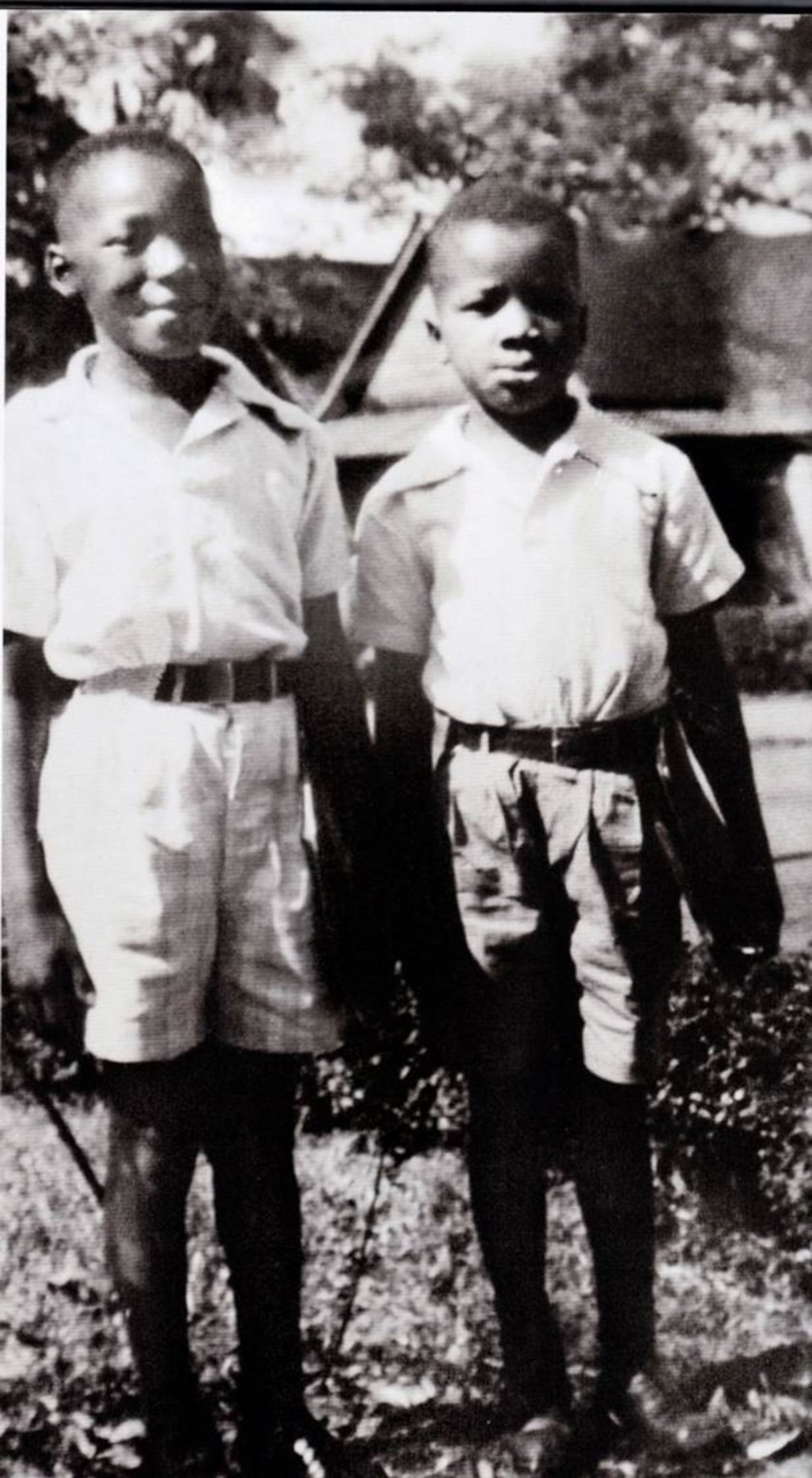

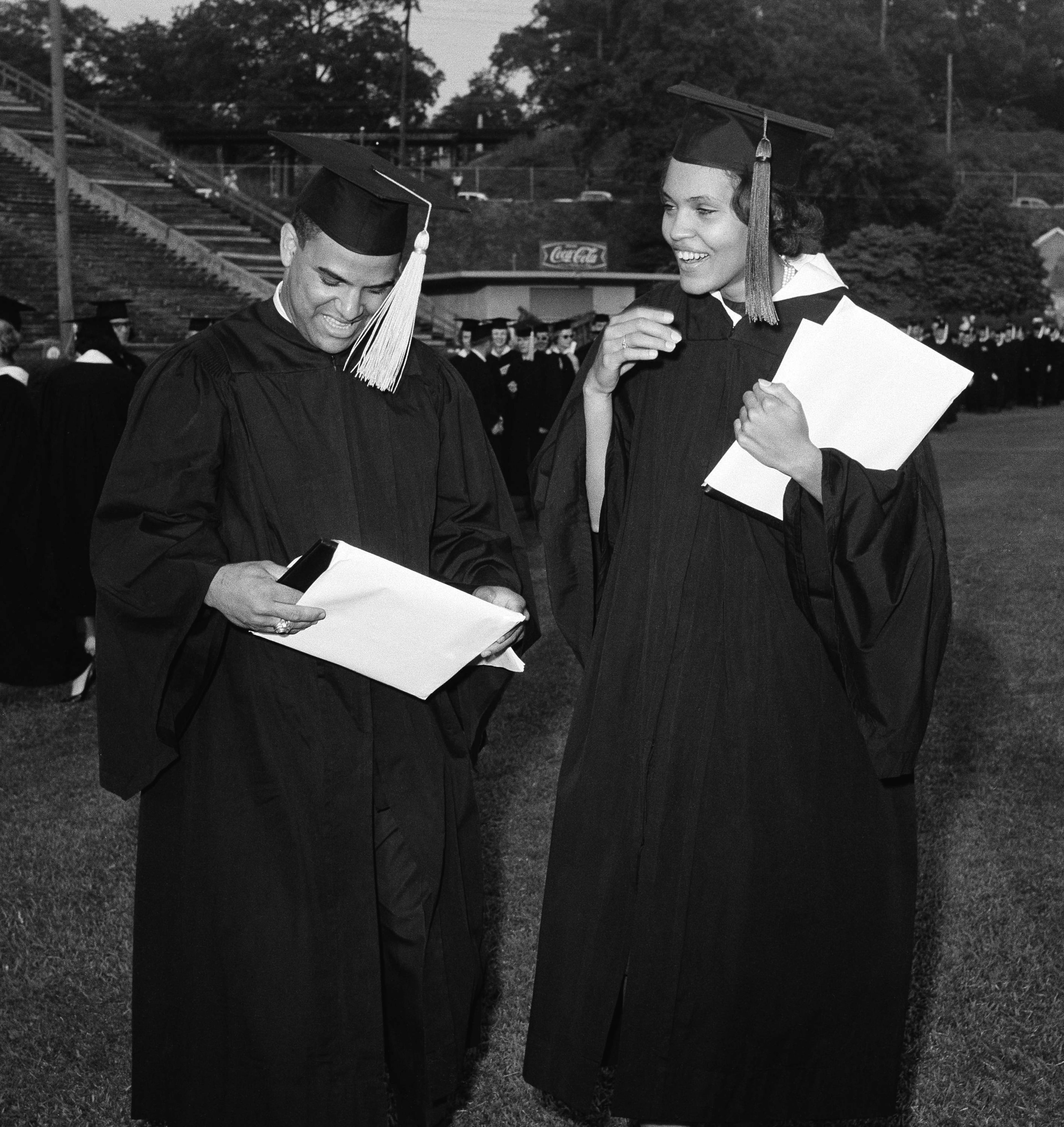

In 1961, under a federal court order, the University of Georgia admitted Hamilton Holmes and Charlayne Hunter, both graduates of Atlanta high schools, making them the first Black students in the institution’s history.

Both students had first applied to UGA as freshmen in 1959 and were rejected. Hunter was told there was no room in the women’s dormitories. Holmes was informed that his application was incomplete, despite having completed an in-person interview.

They sued.

The case landed before U.S. District Judge William Bootle, who, in a ruling on Jan. 6, 1961, dismantled the university’s explanations for rejecting the students.

UGA did have dormitory vacancies and had admitted white women after rejecting Hunter. Holmes’ interview, Bootle wrote, was conducted “with the purpose of finding a basis of rejecting” him.

“Although there is no written policy or rule excluding Negroes, including plaintiffs, from admission to the University on account of their race,” Bootle concluded, “there is a tacit policy to that effect.”

Athens erupted after the ruling. White students gathered at the Arch, sang “Dixie” and shouted racial slurs.

On Jan. 9, Holmes and Hunter registered for classes. Their first days on campus were marked by isolation and hostility. The violence peaked on the evening of Jan. 11, when a crowd gathered outside Hunter’s dormitory, throwing bricks and bottles and setting fires.

Holmes and Hunter were suspended “for their own protection” and escorted out of Athens by the Georgia State Patrol.

What followed surprised many. More than 400 UGA faculty members condemned the riot and called for reinstatement, while Bootle struck down a punitive state law and ordered Holmes and Hunter back to campus days later.

As Holmes and Hunter endured violence and scrutiny in Athens, other institutions across Georgia were watching closely. In September 1961, eight months after UGA’s integration, Georgia Tech quietly enrolled its first Black students. Emory followed. Georgia State integrated in 1962.

That same summer, Atlanta Public Schools admitted nine Black students to four previously all-white high schools. President John F. Kennedy praised the city and state for what he called a “responsible, law-abiding” process.

Holmes and Hunter graduated from UGA just over two years later.

While Atlanta had built the Atlanta University Center, where Black students had excelled since the 1860s, entry into the state’s flagship schools meant access to credentials, networks and authority.

Holmes went on to become the first Black graduate of Emory University’s medical school and later served on UGA’s board of trustees. Hunter-Gault built a distinguished career in journalism, working at such outlets as The New York Times and CNN and, in 1988, becoming the first Black person to deliver UGA’s undergraduate commencement address.

Atlanta’s later political and professional dominance — its lawyers, engineers, administrators and elected leaders — cannot be understood without this quiet, dangerous year.

What no one in Athens could have known then was how quickly the meaning of Black presence at the University of Georgia would be recast.

On March 3, 1962, just 14 months after Holmes and Hunter first tried to walk onto campus, Herschel Junior Walker — whose legacy would later come to complicate and, in some ways, eclipse the university’s long resistance to integration — was born.

1968: Grief and reckoning

In the years after 1961, Atlanta perfected the choreography of orderly change. White and Black leaders spoke the language of moderation as progress was measured and carefully displayed.

Yet the moral urgency of the movement — embodied by Martin Luther King Jr. — could not be managed so easily.

King was Atlanta’s favorite son. Educated at Morehouse College and a Nobel Peace Prize winner by 35, he had become one of the most recognizable Black Americans in the world, carrying Atlanta with him onto the national stage. His authority was moral as much as political, and his presence allowed the city to imagine itself as both progressive and controlled.

That illusion collapsed on April 4, 1968, when King was assassinated in Memphis, forcing Atlanta — and the nation — to confront loss, rage and the unfinished work of freedom.

By the morning of April 9, the day of King’s funeral, Atlanta had already stopped moving. Before dawn, mourners climbed trees along Auburn Avenue, while others claimed rooftops. By midmorning, tens of thousands — men in dark suits and hats, women in Sunday dresses and gloves — pressed toward Ebenezer Baptist Church, filling the streets to see the hearse, to stand in the same air and to bear witness.

Outside Ebenezer, loudspeakers carried hymns and eulogies to the crowd. Inside, dignitaries gathered quietly.

Two mules were brought forward to pull the wagon carrying King’s African mahogany casket. This would not be a motorcade. It would move at a deliberate pace.

The procession stretched 4.3 miles, winding from Auburn Avenue through downtown and the Georgia Capitol, toward Morehouse College.

At the Capitol, armed state troopers stood watch under orders of Gov. Lester Maddox, who refused to close the building or lower the flag. As marchers passed the rifles, church bells rang. Someone began to sing. Soon, thousands joined in: “We Shall Overcome.”

By the time the procession reached Morehouse, the crowd had swelled toward 200,000. King’s journey stitched together Black neighborhoods, political power and moral reckoning in a single line.

The city had prepared for chaos, but remained quiet.

Elsewhere, the nation exploded as more than 100 cities burned after King’s assassination, followed by the killing of Robert F. Kennedy and televised violence at the Democratic convention in Chicago, as faith in reform collapsed.

Atlanta did not burn. But it was changed. King’s death saw the movement’s energy begin to turn inward — toward governance, economics and control of institutions.

Grief sharpened ambition.

In the months after King’s death, Atlanta’s young Black leaders began to consider how the movement would be carried forward.

One was a 30-year-old graduate of King’s alma mater, Morehouse, who, just days after his daughter was born, quit his job at an Atlanta law firm and borrowed $2,500 to run for the U.S. Senate against Herman Talmadge, a segregationist whose family represented the last gasp of plantation politics.

He won less than one-third of the statewide vote in the underfunded campaign but easily carried Atlanta.

In a city still reeling from King’s assassination, it was a signal that something had shifted.

Maynard Holbrook Jackson had arrived.

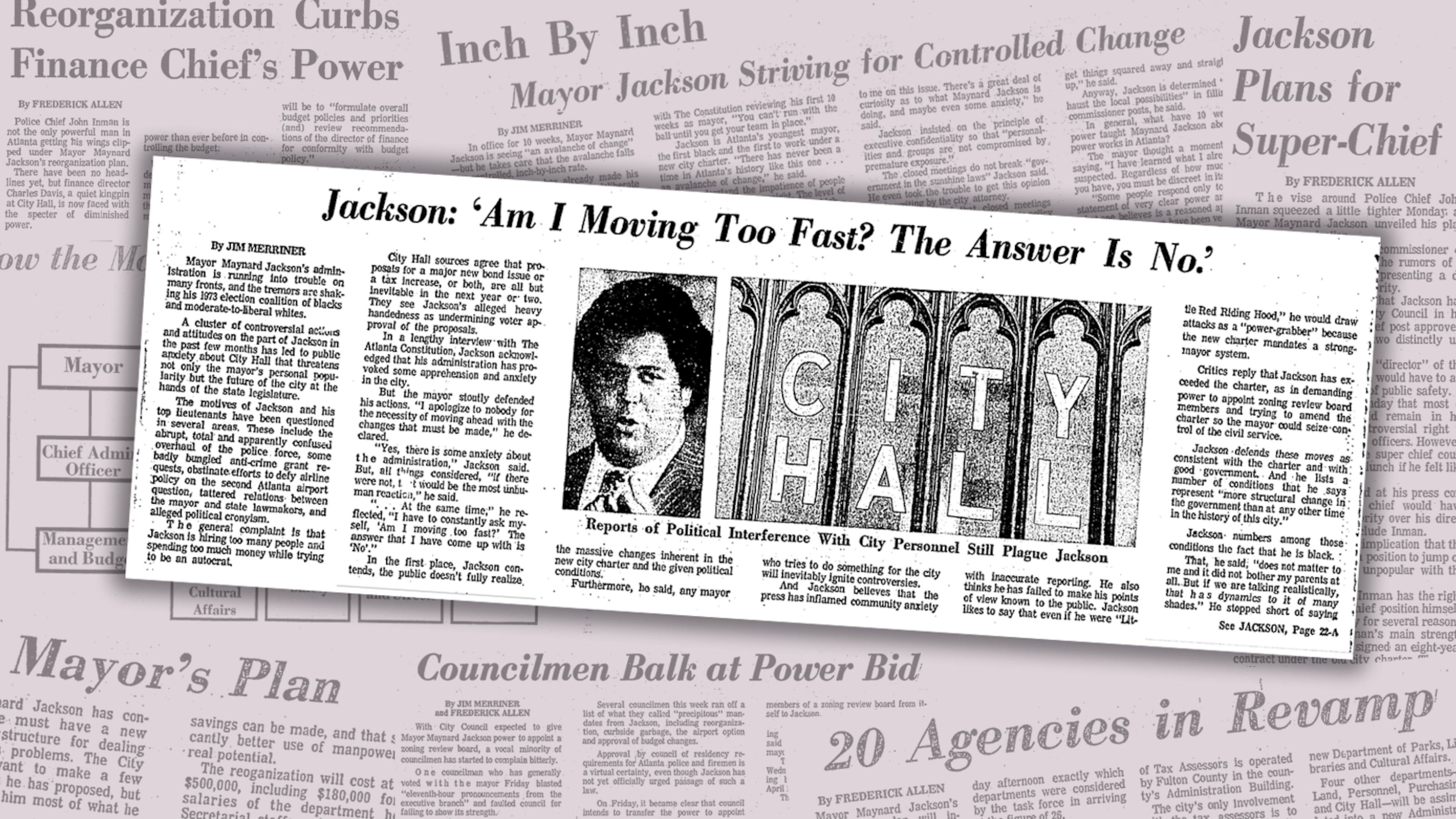

1973-1974: Power takes hold

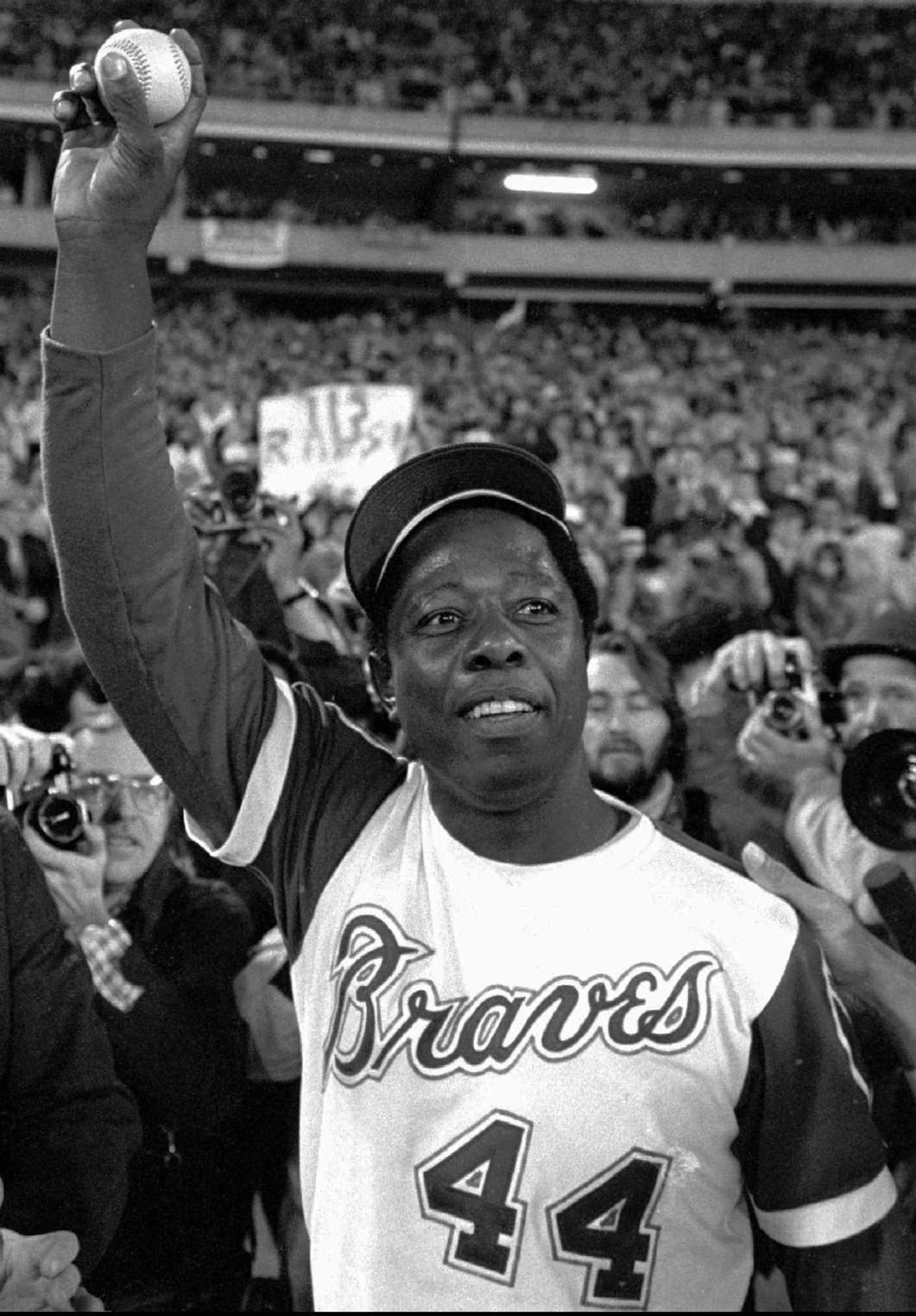

On the night of April 8, 1974, when Hank Aaron launched his record-breaking 715th home run, one of the loudest cheers came from a seat a few rows behind the Braves’ dugout: Mayor Maynard Jackson.

The moment linked two men reshaping Atlanta in different arenas but carrying the same historical weight.

Aaron, affirming Black excellence at the pinnacle of America’s game, and Jackson, newly elected as the city’s first Black mayor, shifting power from symbolism to governance and ushering in decades of Black political leadership.

Together, their milestones marked 1974 as a year when Black achievement in Atlanta moved from endurance to dominance.

But the convergence began months earlier.

On Sept. 29, 1973, Aaron hit a three-run home run — his 40th and final homer of the season — finishing the year at 713, one short of Babe Ruth’s record.

Just three days later, Jackson advanced to a runoff against incumbent Mayor Sam Massell. On Oct. 16, 1973, he won decisively, capturing more than 60% of the vote in a political upset that signaled the unraveling of Atlanta’s old order.

With that victory, Black Atlantans gained control of City Hall for the first time — not only the mayor’s office, but also the City Council and Board of Education.

At the federal level, Atlanta was represented in Congress by Andrew Young, a former aide to Martin Luther King Jr., underscoring how moral leadership was being translated into institutional power.

The symbolism was undeniable, but the structural shift was even more profound.

Jackson inherited a city still divided by neighborhood, wealth and access, that proudly marketed itself as “too busy to hate” while leaving contracts and capital overwhelmingly in white hands.

His administration made power tangible, turning minority participation requirements tied to the expansion of Hartsfield Airport into policy and directing wealth into Black hands.

Governance now enforced what previous protests had demanded.

Then came April.

The 1974 baseball season opened in Cincinnati, on April 4 — the sixth anniversary of King’s assassination. Aaron asked the Reds to observe a moment of silence before the game. The request was denied. Aaron hit a two-run home run in the first inning, tying Ruth at 714.

Four days later, back in Atlanta, history arrived on schedule.

As Aaron circled the bases after No. 715, the crowd roared. Among them sat Jackson, watching a different kind of barrier fall.

One man represented Black political power newly rooted in governance. The other embodied Black excellence that had endured scrutiny and death threats.

If 1973 transferred power, 1974 tested it.

By the end of that year, Jackson moved to institutionalize Atlanta’s cultural future, creating the Bureau of Cultural Affairs to cultivate and sustain artistic expression. Power, he said, was also cultural.

But as Jackson was building a legacy in Atlanta, Aaron was closing his. After the 1974 season, the Braves traded him to Milwaukee, ending his tenure in Atlanta, where he had made history.

On May 27, 1975, now playing out the final stretch of his career as a left fielder and designated hitter for the Brewers, Aaron went 1-for-3 with a pair of RBIs.

A few hours later, in Atlanta, André Lauren Benjamin was born.

1994: Atlanta finds its voice

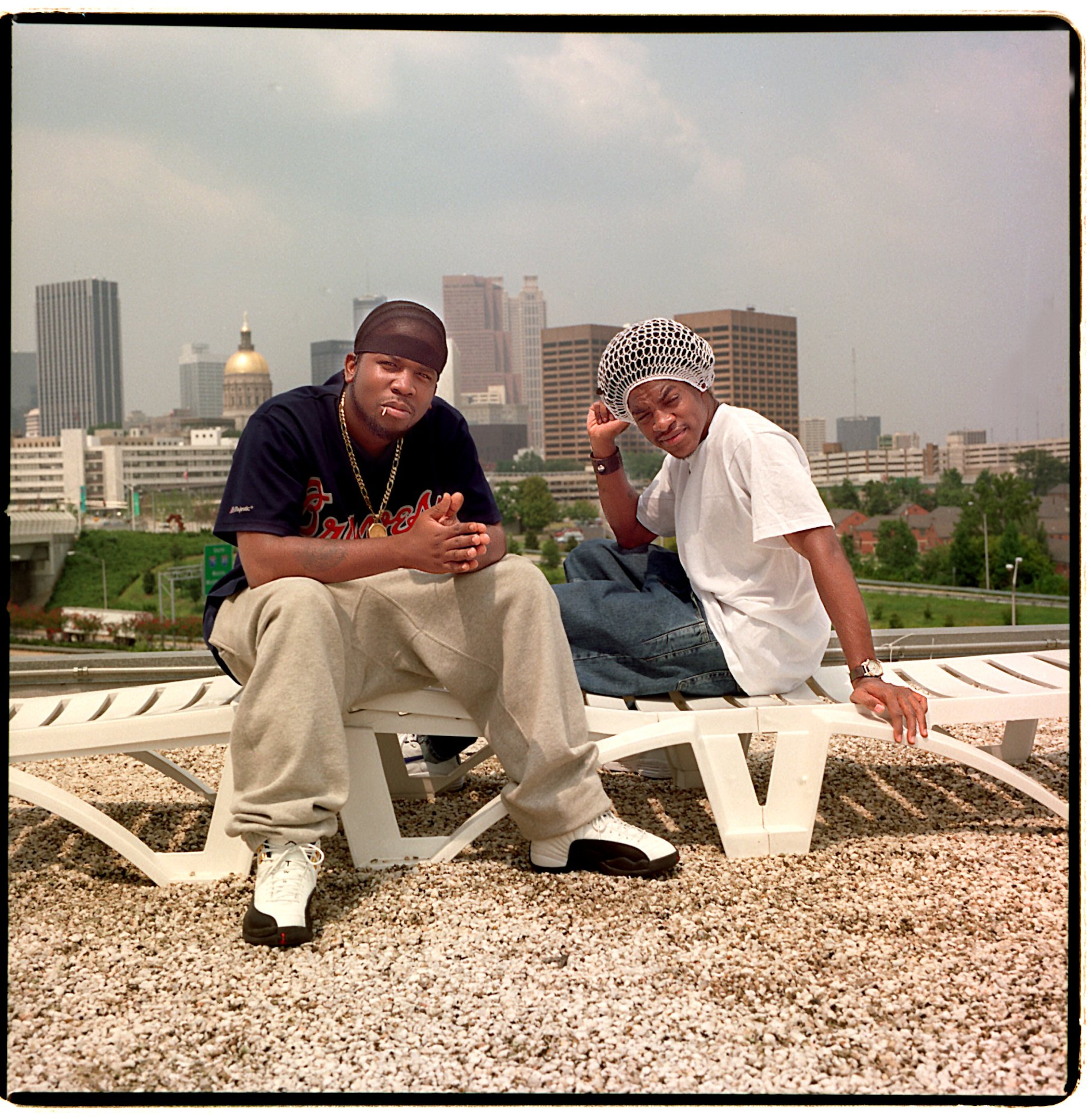

On April 26, 1994, Atlanta announced itself to the rest of the country — not through politics or protest, but through music.

That Tuesday morning, “Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik,” the debut album from two young Atlanta rappers — André 3000 and Big Boi, collectively known as Outkast — arrived.

For years, Atlanta had been defined by Black leadership moving from the pulpit to City Hall, with Martin Luther King Jr. shaping the city’s moral center and Black mayors governing its institutions.

What Atlanta had not yet done was declare itself culturally — on its own terms.

“Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik” changed that.

The album was a revelation, emerging from a city shaped not by the aftermath of the Civil Rights Movement and the gains and limits of a generation that came after the marches ended.

Before 1994, Atlanta’s musical identity was diffuse. The city had produced R&B stars, gospel giants and funk legacies, but hip-hop remained peripheral, often filtered through coastal expectations. New York set the lyrical standard. Los Angeles supplied the attitude.

Despite the success of artists and producers like Arrested Development, Dallas Austin and Jermaine Dupri, Southern artists were still treated as regional curiosities — their accents dismissed, their stories flattened.

That changed one Tuesday morning with the release of “Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik.”

Built on live basslines, church-inflected harmonies and a slow Southern pacing, the album sounded conversational, humid and patient.

It spoke in the unapologetic language of Black Atlanta neighborhoods — the projects, MARTA, survival and Cadillacs.

In one disparaging line, it even name-dropped Maynard Jackson, showing there could be tension between politics and culture.

Just four months after “Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik’s” release, promoter and cultural archivist Jason Orr launched the first FunkJazz Kafé, a genre-collapsing gathering where hip-hop, spoken word, jazz and soul became a shared language.

FunkJazz — where everyone from Jill Scott and Erykah Badu to Doug E. Fresh could appear unannounced — became an incubator for Atlanta’s creative ecosystem, mirroring what the city itself was becoming: layered, experimental and self-defined.

A year later, André 3000 and Big Boi traveled to New York to accept the Best New Rap Group award at the 1995 Source Awards — and were met with boos.

André stepped forward, took the microphone, met the boos and ended the argument in six words: “The South got something to say.”

It was a line about music, but it was also about authorship. Atlanta was no longer begging to be recognized.

Outkast would go on to be inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, becoming one of the most influential rap groups in history, while the city produced a generation of artists — from Goodie Mobb to Future — who made Atlanta impossible to ignore.

The declaration reached beyond hip-hop, reshaping how the city saw itself and how the country saw Atlanta as a cultural engine shaping sound, style, politics and imagination.

On May 14, 1994, weeks after “Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik” was released, Keisha Lance Bottoms — an Atlanta native and the daughter of a former R&B singer, Major Lance — graduated from Georgia State University’s College of Law.

2020: The ‘Atlanta Way’ breaks

Keisha Lance Bottoms was furious.

On the evening of May 29, 2020, she stood at a podium at the Atlanta Police Department alongside Police Chief Erika Shields and hip-hop stars T.I. and Killer Mike and delivered a blunt message to thousands of protesters: “If you care about this city, then go home.”

Outside, Atlanta was in bedlam. Sparked by the murder of George Floyd under the knee of a Minneapolis police officer, what began as a peaceful protest had devolved into destruction. Marchers ransacked parts of the city, smashing windows, looting stores and setting police cars on fire.

“This is not a protest,” Bottoms said. “This is not in the spirit of Martin Luther King Jr. This is chaos. A protest has purpose. When Dr. King was assassinated, we didn’t do this to our city. You are disgracing our city. You are disgracing the life of George Floyd and every other person who has been killed in this country.”

As the city burned, it was clear that Atlanta had lost its way.

For decades, the city had prided itself on following “The Atlanta Way.” Andrew Young had championed the term, built on the idea that even the city’s hardest moments could be navigated through restraint, coalition and patience.

That approach helped explain why Atlanta never became Birmingham or Little Rock during the Civil Rights era and how the Southern city went on to build the world’s busiest airport and host the 1996 Olympics.

But in 2020, that idea finally cracked.

And at the center of the storm stood Bottoms, Atlanta’s 60th mayor and its second woman to hold the office, facing a city unraveling on multiple fronts.

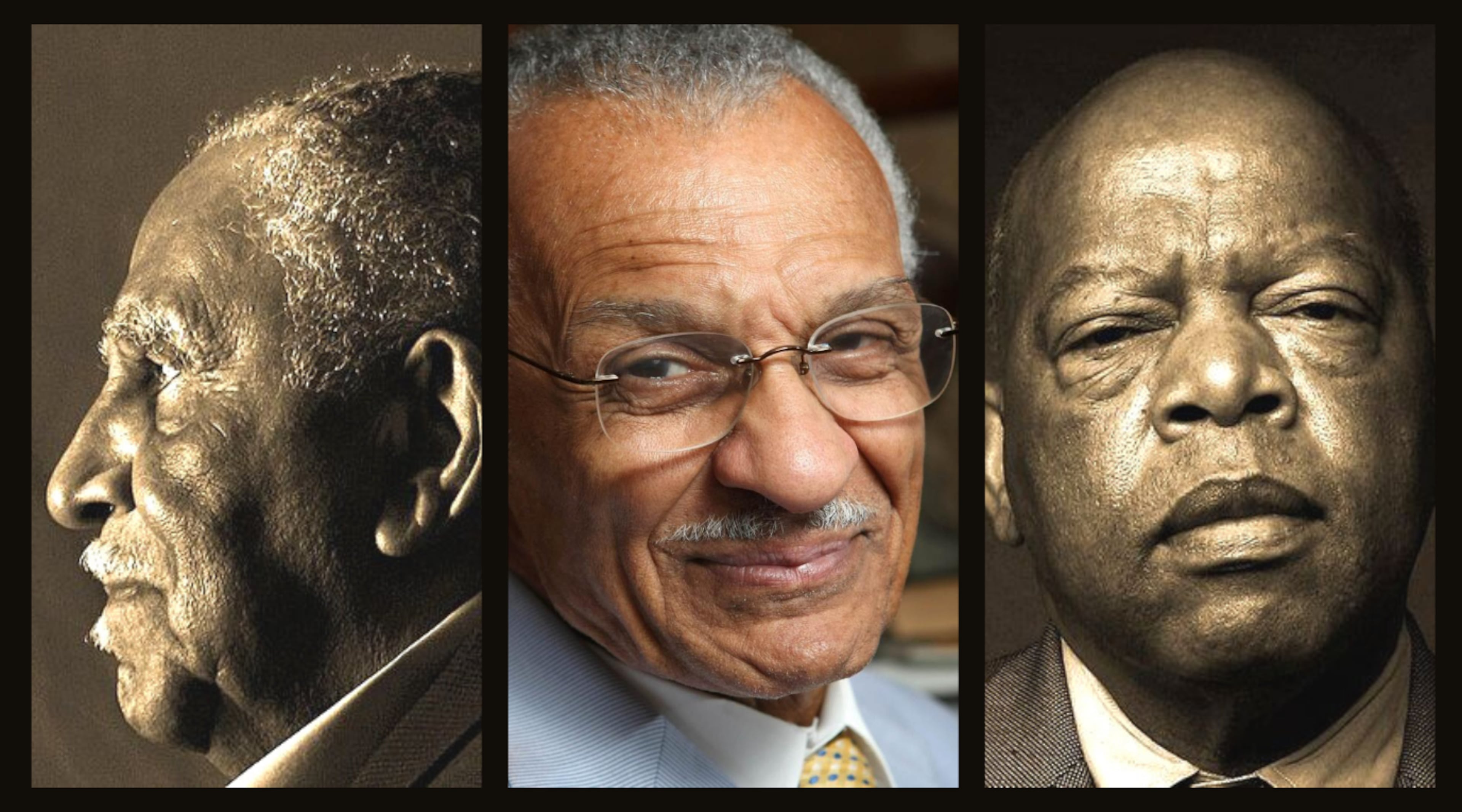

The year opened in mourning.

Within months of one another, Atlanta lost three pillars of the civil rights era and Presidential Medal of Freedom winners — Joseph Lowery, John Lewis and C.T. Vivian — who had marched and bled the city into a symbol of Black political progress.

Their deaths closed a chapter of moral authority.

The city was already grieving when the world shut down.

COVID-19 arrived quietly, then relentlessly.

Churches closed. Schools emptied. Streets thinned. The virus tore through Black communities strained by health inequities and economic vulnerability.

More than 42,400 Georgians died, with Atlanta bearing a disproportionate share.

Weeks after the George Floyd protests, the fracture deepened. In June, Rayshard Brooks was shot and killed by a police officer outside a Wendy’s in southwest Atlanta. Protests returned to the streets. The restaurant burned.

The city’s moral center shifted again because Atlanta could no longer claim distance from the violence it condemned.

By year’s end, 2020 had stripped Atlanta of its illusion that progress was manageable without reckoning. What remained was grief, anger and a generation with little patience for process.

The old guard was gone, and the systems they built were under siege.

If 1968 shattered Atlanta’s innocence and 1973 restructured its power, 2020 forced the city to confront itself without certainty that the old ways still worked.

The Atlanta Way did not survive 2020 intact.

On May 6, 2021, almost a year after the protests, Keisha Lance Bottoms announced she would not seek reelection as mayor.

As of today, Bottoms is widely viewed as a leading Democratic contender for governor of Georgia.

What comes next is still being written.

This year’s AJC Black History Month series marks the 100th anniversary of the national observance of Black history and the 11th year the AJC has examined the role African Americans played in building Atlanta and shaping American culture. New installments will appear daily throughout February on ajc.com and uatl.com, as well as at ajc.com/news/atlanta-black-history.