Mixed reactions as portrait of Mormon founder unveiled at Morehouse

On the first day of Black History Month, two portraits were added to the collection inside Morehouse College’s International Hall of Honor. Inside the Martin Luther King Jr. Chapel and Plaza, the hall has more than 200 oil portraits of global leaders representing what the historic Black men’s college calls “the international civil and human rights movement.”

Those portraits include iconic figures Rosa Parks, Nelson Mandela, Oprah Winfrey, former Atlanta mayors Shirley Franklin and Maynard Jackson, and various past presidents of Morehouse, such as the Rev. Benjamin E. Mays.

One of the new portraits is of Harold V. Bennett, a professor and current Martin Luther King Jr. Endowed Chair in the Philosophy and Religion Department at Morehouse.

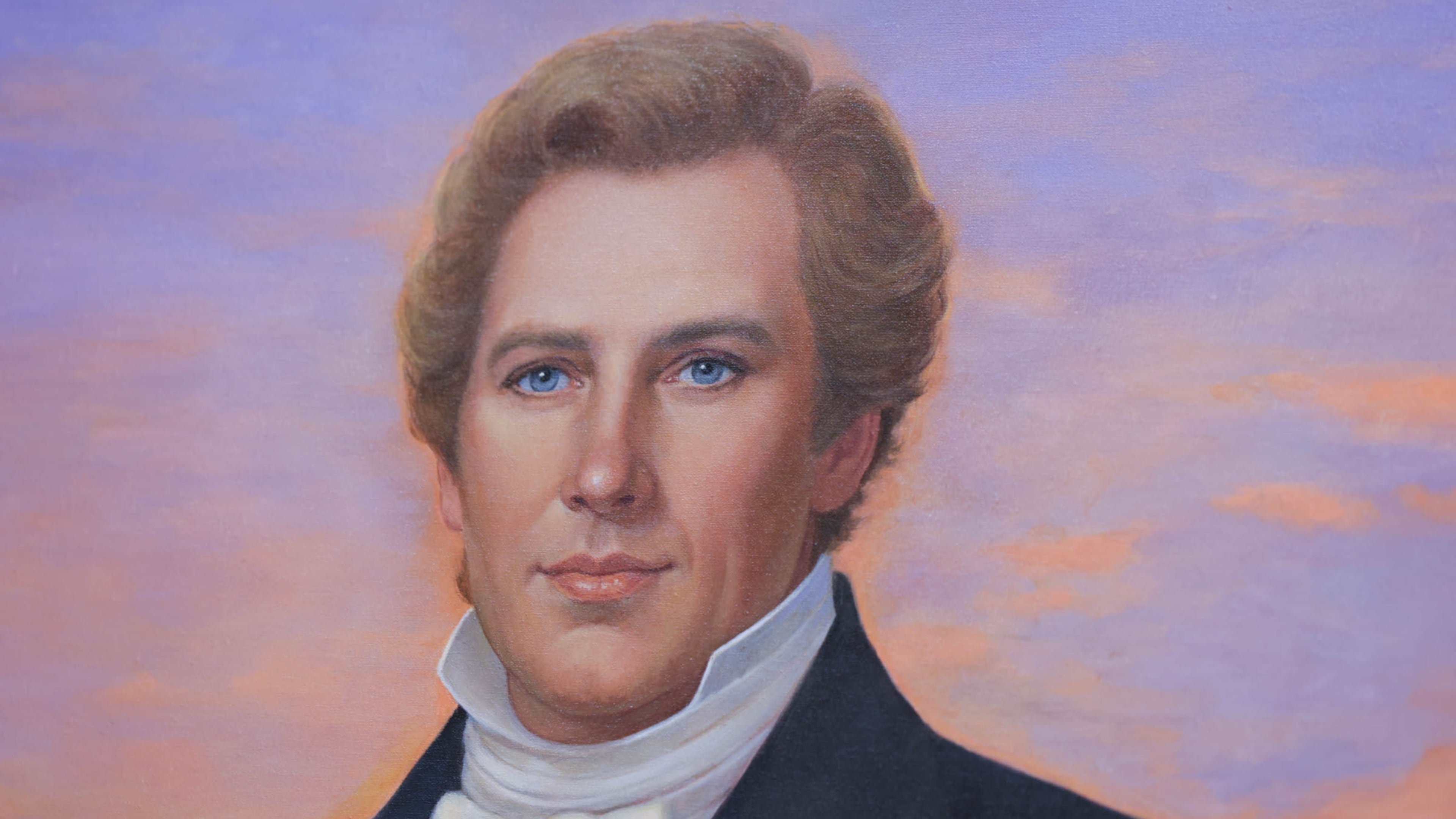

The other — that of Joseph Smith, the founder of Mormonism — has stirred controversy and sparked questions on campus and beyond. Smith’s writings that include a defense of slavery have some questioning why one of the nation’s most prestigious HBCUs would include a statue of him.

“I don’t think that really aligns with the values of Morehouse and its legacy, specifically social justice-based gospel,” said Nathaniel Whitaker, who graduated from Morehouse with an Africana studies degree in 2024. “This could have been an opportunity for Morehouse to uplift another Black male innovator, given that it’s a Black male college.”

The unveiling of the painting, titled “Sunset on Nauvoo,” comes at a complicated time, with Morehouse celebrating Founders Week and the founding of the college Feb. 14, 1867.

Efforts to contact Morehouse for comment were unsuccessful.

Smith’s views on slavery

During his 1844 campaign for U.S. president, Smith signaled an openness to abolishing slavery. In an 1844 campaign pamphlet, Smith wrote that if he were elected, he would “honor the old paths of the venerated fathers of freedom.”

“I would use all honorable means to have their prayers granted and give liberty to the captive,” he wrote.

This position signaled an evolution for Smith, the founder and first president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. However, in other preserved documents dating back to 1836, he is on record quoting the Bible as justification for slavery’s continuance. In some cases he connected enslaved Africans to “the sons of Ham,” suggesting that slavery was sanctioned by God.

“All men are to be taught to repent; but we have no right to interfere with slaves contrary to the mind and will of their masters. In fact, it would be much better and more prudent, not to preach at all to slaves, until after their masters are converted: and then, teach the master to use them with kindness, remembering that they are accountable to God, and that servants are bound to serve their masters, with singleness of heart, without murmuring.”

During the same period, Smith allowed Black men to be ordained into priesthood and become missionaries. After his assassination, a Black woman named Jane Elizabeth Manning James was sealed — a term meaning bonded to a person or their family by a Mormon priest — to the Smith family, for whom she had worked. She was a devout Mormon but because of her race, she was sealed not as a family member but as a servant, for eternity.

In 1952, Brigham Young, the Church’s second president, instituted a ban on Black men reaching Mormon priesthood and restricted Black people from entering Church temples. This policy was enforced until 1978, and is often incorrectly attributed to Smith.

The hall’s Mormon men

The collection of portraits is not exclusively of Black people.

Those in the portraits represent a spectrum of humanity, from Bishop Mariann Edgar Budde, the first female bishop of the Washington diocese, to Abraham Lincoln, hanging vertically between paintings of Robert Sargent and Eunice Kennedy Shriver. There’s also a portrait of President Jimmy Carter, Irish activist and Nobel Peace Prize winner Betty Williams and former Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin.

On the wall where Smith’s portrait is to be displayed, he would be one of several members or affiliates of the Mormon faith shown.

His portrait will join those of billionaire Bill Marriott, chairman emeritus of Marriott International who briefly served as a Mormon bishop; Russell Marion Nelson, former president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints; and business owner Spencer Eccles, whose grandfather David Eccles, a prominent 19th century Mormon industrialist, was Utah’s first multimillionaire.

‘Lincoln before Lincoln’

In a statement released by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Lawrence Edward Carter Sr., the longtime dean of Morehouse’s Martin Luther King Jr. International Chapel, praised Smith’s 1844 run for U.S. president and his political platform as justification for the hall’s inclusion of his portrait.

Carter called Smith’s plan to abolish slavery “among the most morally ambitious proposals of the antebellum era.” He also suggested that by taking such a public stance against enslavement, he was essentially putting his own life at risk and increasing the likelihood of his own assassination.

“Joseph Smith Jr. was Lincoln before Lincoln,” Carter said in the statement.

He gave an interview to the Maroon Tiger, Morehouse’s student newspaper, after the unveiling earlier this month. “Smith wanted to free the enslaved Africans, and he wanted to have the federal government pay reparations to slave owners,” Carter said. “If elected, there would have been no Civil War.”

It is not known if the commissioning of the hall’s oil paintings involves a fee or financial transaction, but Carter is quoted in the Maroon Tiger mentioning difficulty in finding donors willing to pay for paintings.

“Donors are hard to find who are willing to pay for oil portraits of people they don’t know,” he said. “I haven’t been able to find money for almost everybody you can name in Black history.”

The portrait’s Mormon roots

Visual artist Connie Lynn Reilly, an Atlanta native and member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, was commissioned to create the painting. She has 10 additional commissions with Morehouse for portraits coming to the hall.

According to Reilly, the painting will be hung in early April, in time for the unveiling of others she was commissioned to paint on April 9.

“I’m extremely honored to be chosen,” she said in a phone interview. “It’s a spiritual thing for me as a member of the church because it’s meaningful to us. We don’t worship Joseph Smith; we worship Jesus Christ. But he was the instrument the Lord used to restore his gospel to the world.”

Reilly said she was honored to have her work displayed at the Black men’s college, and she believes the painting represents a path to finding common ground among our differences.

“We should love one another. We’re all part of the same family of God. We need to stop all this bickering about differences and just come together and love one another. I feel like love is healing, and it can heal the whole world if we have that in our hearts.”

A relationship between Morehouse and the church has been developing in recent years. In March 2023, Morehouse awarded Nelson the school’s inaugural Gandhi-King-Mandela Peace Prize, which is given to individuals who promote peace and positive social transformation through nonviolent means. Carter bestowed the award on Nelson.

In September 2024, the Mormon Tabernacle Choir performed with the Morehouse and Spelman glee clubs inside the chapel’s auditorium.

Craig Ballard, chairman of the Joseph Smith Jr. and Lucy Mack Smith Family Organization, attended the unveiling.

According to its website, the group encompasses multiple family organizations and serves “to coordinate resources and activities for the benefit of the entire family.”

Student and alumni concerns

Still, there are questions about the portrait on campus.

There have been several statements made from students and alumni, including the Martin Luther King Jr. International Chapel Assistants Program, a student-led group. They released a statement on Instagram earlier this month expressing concern about the decision to accept and unveil the portrait of Smith.

“Honoring a figure associated with a religious tradition whose early history includes racially exclusionary teachings and practices does not align with Morehouse’s mission or heritage. Such an action does not reflect the Morehouse standard, nor the standard upheld by the Chapel Assistants Program,” reads an Instagram post signed by Alonzo Brinson and Damarion King, the president and vice president of the program.

They go on to request, “with righteous indignation,” that the portrait be returned to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Whitaker, the 2024 graduate, said he was disappointed when he heard about the portrait. He said he hopes it is returned to the donors. He suggested a Mormon foundation’s headquarters would be a proper place for it to be displayed.

Whitaker also clarified that his displeasure with the portrait is an institutional issue and not something he blames on Carter, whom he said he respects.

“Why do we as Black institutions have to be the door-openers to center things not of our culture? I don’t think it’s a racist or prejudiced thing to center things of our culture, especially in this climate. I kind of had a read-the-room reaction. Is this the time to do that?”