My love for Black Barbie is an ode to my ancestors

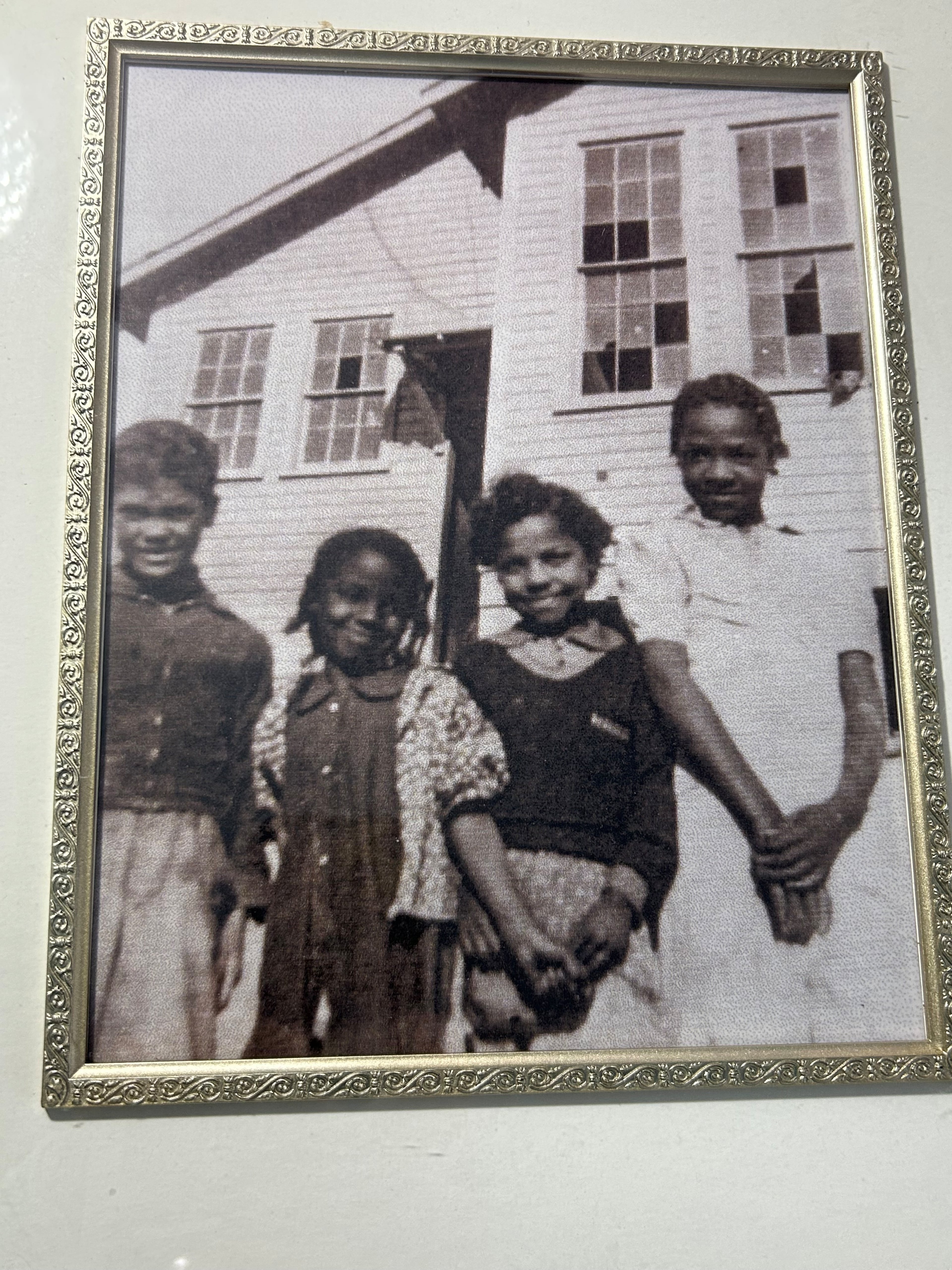

Family lore has noted the no-nonsense nature of my maternal great-grandmother Sarah. Older cousins and aunties have sworn about the tight ship she ran on her southeastern Kentucky farm. Born in 1886 and with no more than a third-grade education, Sarah maintained the family property that passed to her from our formerly enslaved ancestors and continues as part of our family legacy.

Along with land, hard work was inherited — especially by the women. Even as children, they worked odd jobs, contributing financially where they could.

Play was a luxury they were rarely afforded.

Like many Black girls of that era, they were subjected to racialized sexism and adultification that demanded responsibility before innocence.

My generation had the chance to change that narrative. We could be softer in ways the women before us could not have imagined. We had the freedom to play, make believe, visualize worlds outside our own.

For me, that freedom took the shape of Barbie. Playing with dolls — especially Black Barbies — allowed me to imagine myself as anything. Only later did I understand that this was never just play.

It was a matter of rebellion.

I’m the first generation in my maternal lineage to not be born enslaved or under Jim Crow.

My collection of nearly 400 Barbie dolls is an act of remembrance — honoring every Black girl who was forced to grow up too quickly, including the women who raised me.

Collecting Black Barbie is a way of reclaiming innocence they were denied and femininity they had to conceal for safety.

“I remember being excited just being in the Barbie section,” my mother, Theresa, told me recently about buying the dolls for me as a child. “I think I kind of went into little-girl mode during those times when I’d pick them out for you. ... I think it’s because I never received a Barbie (as a little girl).”

For decades, Barbie has been considered the premier tier of fashion dolls. Occasionally, my mother, her sisters and cousins were awarded other fashion or paper dolls in their meager childhoods. But nothing equaled the quality of Barbie.

I didn’t become an adult Barbie collector until I was 28, when several dolls started to catch my eye in 2016. That year, the Fashionistas line introduced multiple skin tones, body types and hair textures.

“Barbie the Look” line revived ultra-glam styling reminiscent of the maximalist era of the 1990s. It felt like I was a kid again.

I always held an appreciation for the different iterations of the doll over the years. And as a lover of nostalgia, I never got rid of my childhood collection.

They came as two time capsules: one that inspired me into varying facets of womanhood and the other that reassured my Black mother that her daughter could be free.

I didn’t realize the importance of that second representation until I was older and looked back on my old toys.

While visiting my childhood home, I’d go through my collection and find my mom would be just as excited to revisit my dolls as me.

“Every time I would go to the Barbie department and I’d see they would have new ones, I would say, ‘Oh, man! They have Black ones now!’” my mother said. “It just made me excited that they thought about us little Black girls and made dolls for us.”

My mom chose dolls thoughtfully, imagining how each might shape my sense of self.

Black like me

Black dolls existed before the Shani line, but Shani was different. Released in 1991 within the Barbie universe, the collection featured varied hues of melanin, hair textures and unmistakably Black names. My mother chose Asha and Jamal, and they ignited a sense of identity and recognition within me, even when I was just 3 years old.

“I thought (Asha) was pretty,” my mom later told me. “I thought you may relate to her. I thought maybe you would think you were like her or she was like you.”

The Shani line was developed by Kitty Black Perkins, the first Black Barbie designer.

Perkins created the first Black Barbie in 1980 and later developed collections that reflected Black women’s style and sophistication across decades, like the Fashion Savvy Collection in 1998, which consisted of a pair of Black dolls showcasing sophisticated clothing trends for late-1990s Black women.

I grew up with Tangerine Twist from the Fashion Savvy Collection.

Substance and style

Barbie is a political figure. Despite feminist critiques about the sexist woman she purportedly portrays and her unachievable body dimensions, Barbie is progressive. She’s made statements through her fashions and hairstyles. She’s taken a stance with every career she adopts. Each doll release is a relic of the social climate for that time.

I didn’t obtain a mint-in-box version of the first Black Barbie until just last year. Immediately, I understood her historic value. Considering I had been collecting for 10 years and never ran across one during a sale or auction, obtaining her was an ancestral duty.

Though I knew she was a high priority on my list, I had no idea how important her existence truly was for my mom and aunts.

“It was exciting that we finally had a Black Barbie,” my mother’s sister, my Aunt Ada, told me recently. “When I grew up, they didn’t have any (Barbies) of color.”

My mother’s youngest sister, Mattie, agreed.

“It’s about time,” Aunt Mattie recalled about the first Black Barbie. “How long did it take for us to get dolls that looked like us — that weren’t the little cheap, knockoff things?”

Their memories trace back to scarcity.

My grandmother Lelia, Sarah’s youngest daughter, followed in line with her older sisters. After graduating from high school — no small feat for a Black woman in 1940s backwoods Kentucky — she had no other option but to become a housekeeper for white families.

It was a job that was more readily available for Appalachian Black women during a time when segregation was still legal.

In 1964, Lelia passed away due to complications related to postpartum depression.

My mother, then 7, became the oldest caretaker in a household that had few toys and no room for dolls. She and her three younger siblings moved in with their maternal aunt Atha — a local activist and businesswoman — just off from the town railyard.

She told me countless stories of their humble upbringing. She had to cook, clean and assist Atha as “the help” at white homes. She and her sisters found loose pieces of coal that had fallen off trains to warm their house near the railyard.

Barbie dolls were completely out of the question.

As adults, my aunts made a promise: their daughters would have Barbies.

“I always told myself when I have my kids and I got old enough that I would buy them Barbies and they wouldn’t get the cheap knockoffs,” Aunt Ada said. “That’s why they got so many because I couldn’t get one, and I always wanted one.”

My mom was the same. She planned purchases carefully, returning again and again.

Brooke's mother reminisces on Barbie

Theresa details memories shopping for her daughter for a toy she never got to have as a child.

As a little girl, I rarely saw other Black girls who loved Barbie the way I did.

When I was 9, I moved to Cincinnati into a predominantly Black neighborhood. There were plenty of kids on my street, but only one other Black girl played with Barbie.

Now I wonder how many of them were simply never given permission to play.

Instead of creating and imagining their own worlds, the girls from my childhood were more concerned about boys or other issues I was not privy to.

What would it have meant to hold a doll that looked like them — to imagine freely?

How would it have changed the way they viewed themselves over the course of their lives?

Today, my collection includes nearly 400 dolls, many of them Black, representing careers, hairstyles, and possibilities my ancestors could not access. Barbie’s Inspiring Women series — featuring Ida B. Wells, Bessie Coleman, Katherine Johnson, Rosa Parks and Madam C.J. Walker — feels almost unimaginable when placed against my family’s history.

I collect not out of nostalgia alone, but purpose. Each doll stands in quiet defiance of a world that denied Black girls time, softness and imagination.

Even now, my mother and her sisters light up watching the collection grow — proof that something withheld from them has finally been restored.

This year’s AJC Black History Month series marks the 100th anniversary of the national observance of Black history and the 11th year the AJC has examined the role African Americans played in building Atlanta and shaping American culture. New installments will appear daily throughout February on ajc.com and uatl.com, as well as at ajc.com/news/atlanta-black-history.