When Georgia tried to silence Julian Bond

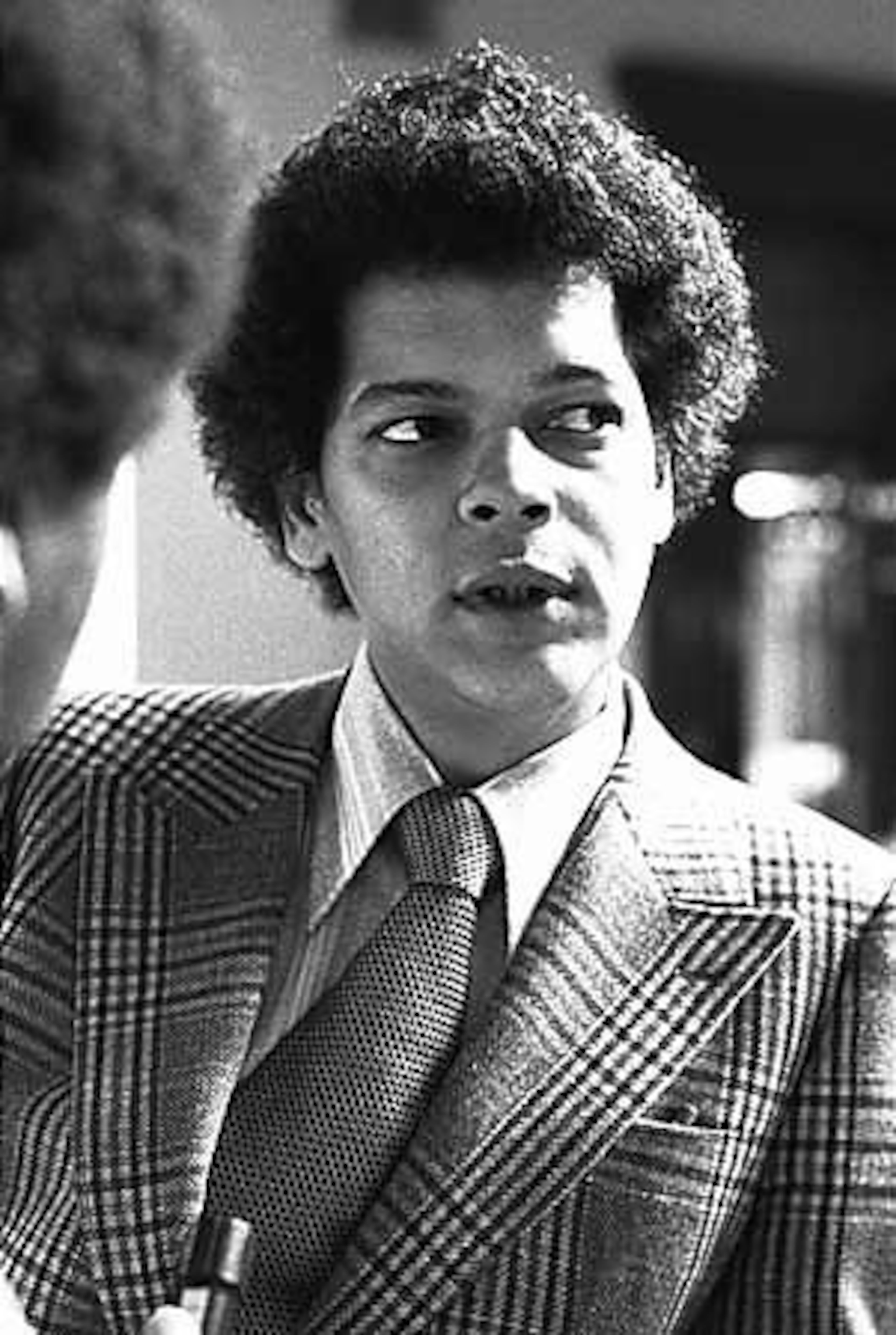

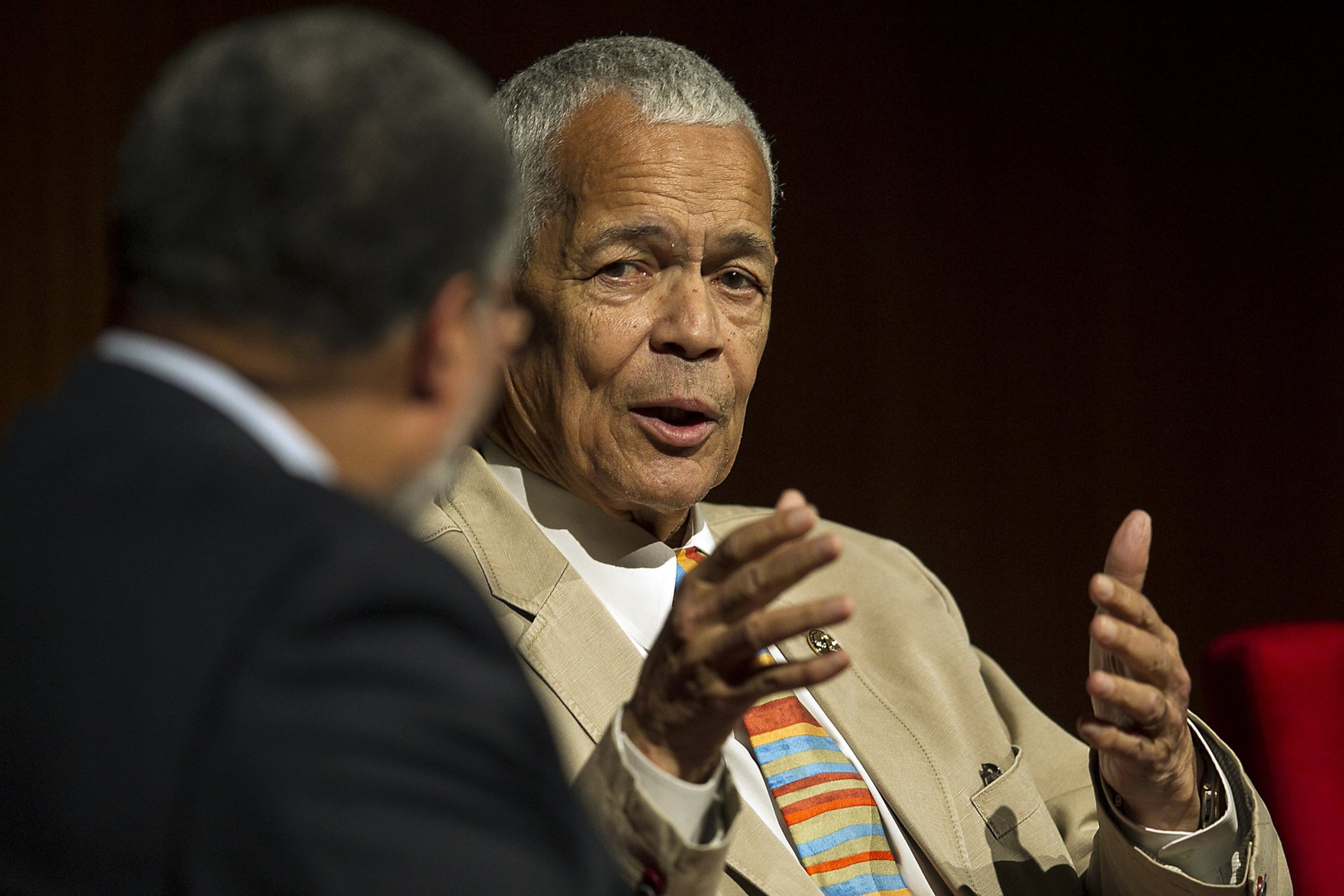

By the winter of 1966, Julian Bond, then 26, had become a familiar presence in Atlanta.

In Atlanta, the unofficial capital of the Civil Rights Movement, crowded with figures who shaped the era, Bond moved easily through the city’s overlapping worlds of campus activism, church basements and pressrooms.

A slim, soft-spoken Morehouse College student, Bond turned protest into language the nation could not ignore.

This year marks the 60th anniversary of the moment that would define Bond’s public life: his election to the Georgia House of Representatives and the state’s extraordinary effort to bar him from taking his seat.

The confrontation, triggered by Bond’s refusal to recant his opposition to the Vietnam War, evolved into a landmark Supreme Court case that tested the reach of the First Amendment and the limits of Southern resistance to Black political power.

The passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and Voting Rights Act in 1965 had opened a door. At that time, Black candidates across the South were seeking to wield power.

In 1965, Bond was elected to the Georgia House of Representatives, one of 11 Black lawmakers sent to the Capitol by voters who believed the movement now belonged inside legislative chambers.

“Julian Bond was front and center everywhere,” recalled Tyrone Brooks, who was then working for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

The thrill of victory did not last long.

On Jan. 10, 1966, the Georgia House voted 184-12 to refuse to seat Bond. The charge was disloyalty. Bond had publicly endorsed a statement opposing involvement in the Vietnam War, a position shared by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the organization he had helped found and once served as communications director.

To many white legislators, the SNCC had come to represent defiance itself. Seating Bond would legitimize dissent they considered dangerous.

To Bond’s family, the rationale was transparent.

“He was somewhat embittered about it because of the way that he was treated,” said his son, Michael Julian Bond, a longtime member of the Atlanta City Council. “He felt that it was his right to freedom of speech to take the stances that he did.”

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., who taught Bond philosophy at Morehouse College, spoke out on his behalf.

Eugene Patterson, then editor of The Atlanta Constitution, condemned the House’s actions.

After Bond’s seat was declared vacant, he ran in his district and won two more times, but he was still not allowed to take his seat in the Legislature.

The fight did not end there.

Bond took his case to federal court, lost and then appealed, and the case moved to the United States Supreme Court.

“The national media, television, the Black press covered him heavily because of his stance on the war and because the General Assembly refused to seat him,” said Brooks, who was elected to the Georgia House in 1980 and spent 35 years in the chamber. “That case captivated Black America.”

Atlanta’s civil rights infrastructure mobilized.

The clash with the General Assembly did not come out of nowhere. Bond had been shaped early by institutions that trained him to challenge authority.

Bond was born in 1940 to Horace Mann Bond, the first Black president of Lincoln University, a historically Black university in Pennsylvania, and a former president of Fort Valley State University, and to Julia Washington Bond, an educator.

Bond grew up in classrooms, lecture halls and faculty living rooms. When his father became dean of education at Atlanta University in 1957, the family returned South, placing Bond at the center of Atlanta’s Black intellectual elite.

At Morehouse, he helped lead sit-ins, including a protest at Atlanta City Hall that landed him briefly in jail. He learned early how the Georgia Capitol enforced its rules. On one visit as a student, he and other Black classmates were escorted out of the whites-only gallery by Capitol Police.

His exclusion as a politician had simply taken a more formal shape.

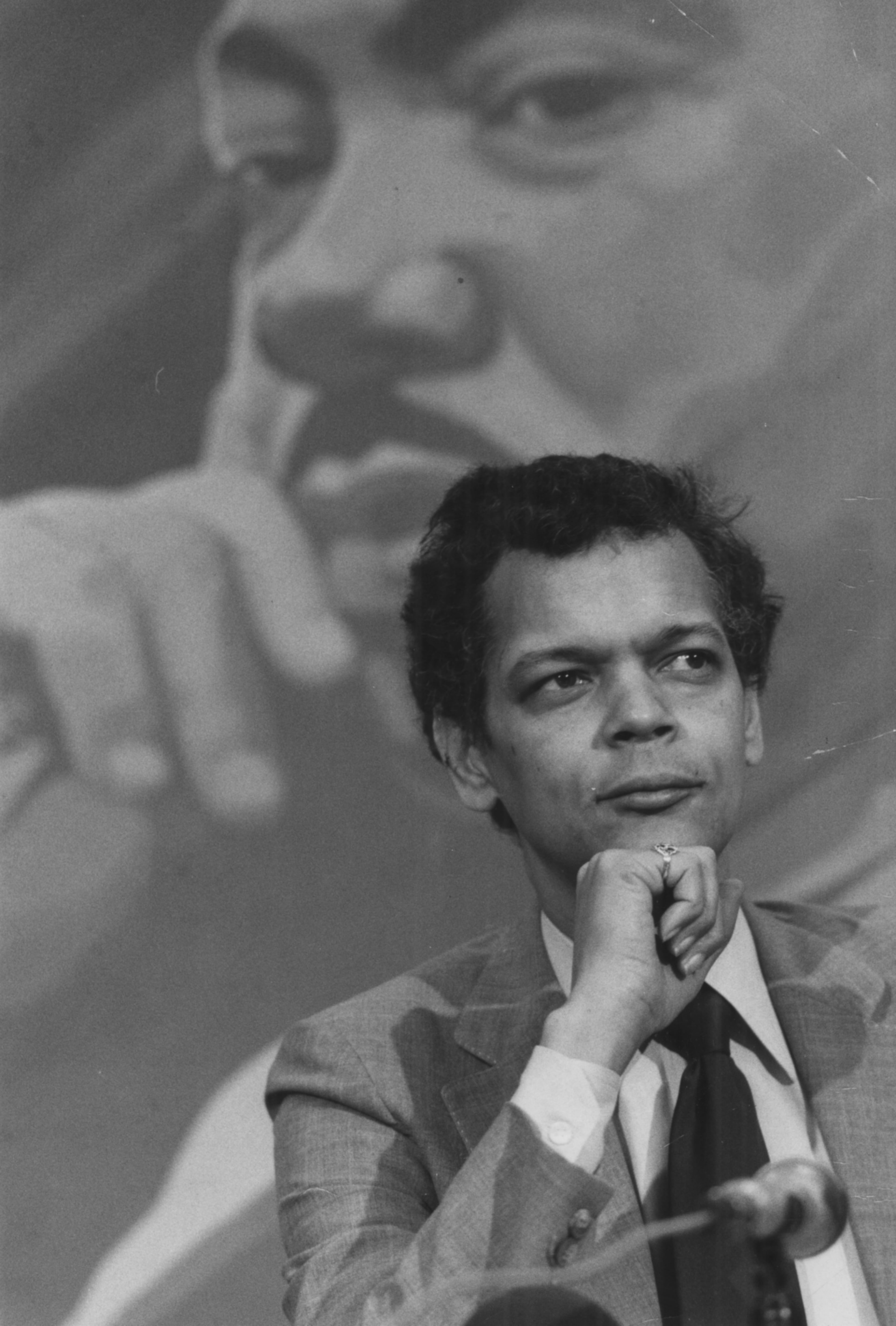

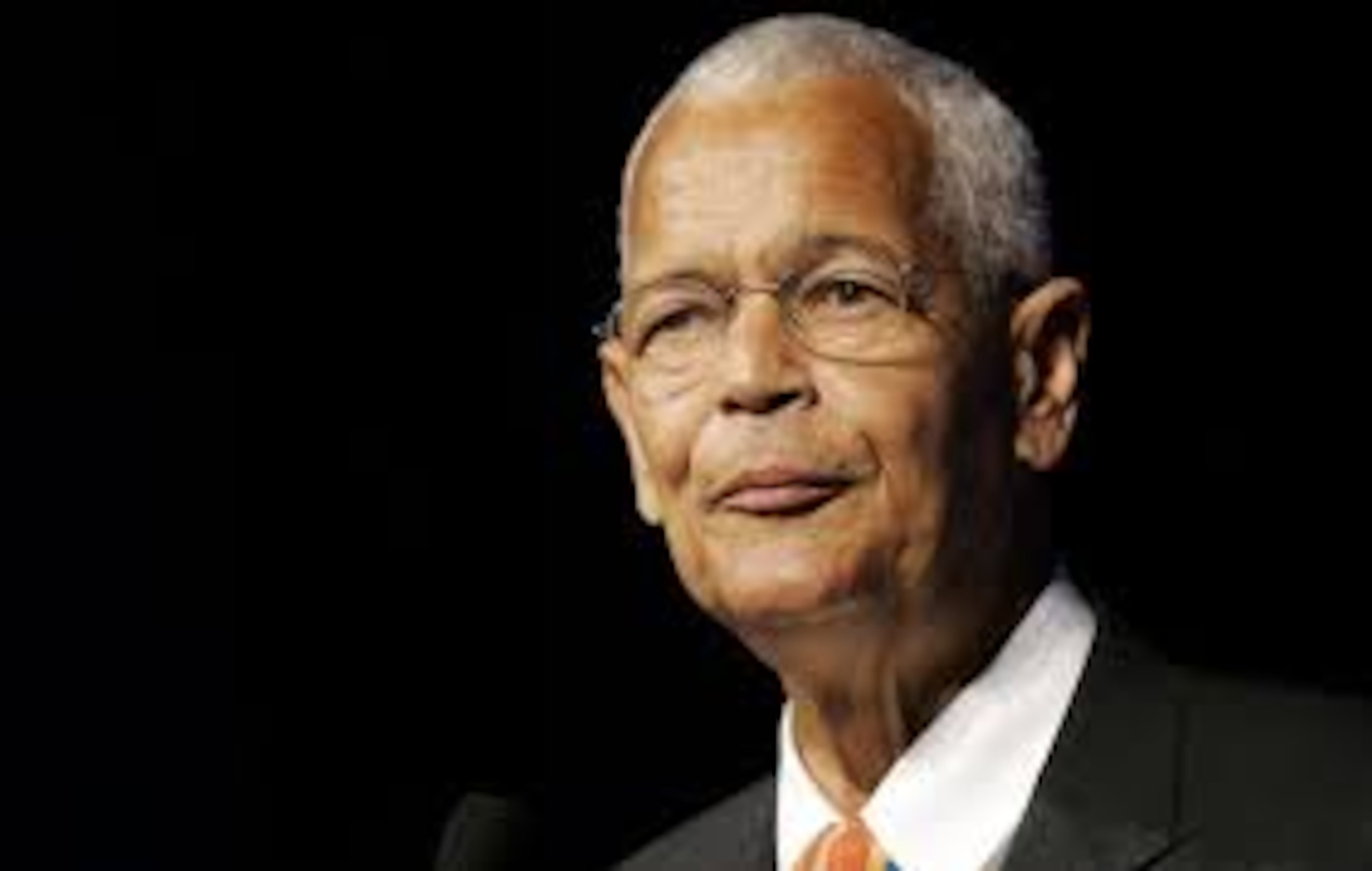

In December 1966, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously in Bond v. Floyd that the Georgia House had violated Bond’s First Amendment rights. The state could not bar an elected official for expressing opposition to government policy. Free speech, the court made clear, did not stop at the Capitol door.

When Bond took the oath of office on Jan. 9, 1967, his mother watched from the gallery. One lawmaker, Rep. James H. “Sloppy” Floyd, protested loudly, calling Bond a “shame and disgrace.”

The House seated Bond and gave him $2,000 in back pay for the session he had been denied. The confrontation ensured he would never again be anonymous under the Gold Dome.

“Julian was a very courageous guy who was willing to die for what he believed in,” Brooks said. “He set the standard. There ought to be a portrait of him in that building.”

Bond’s victory over the Legislature established him as a national figure at the hinge point between protest and governance.

So much so that in 1968, Bond led an alternate delegation from Georgia to the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. He became the first Black person nominated for vice president of the United States.

But at 28 years old, he was too young to accept the nomination and went back to the General Assembly.

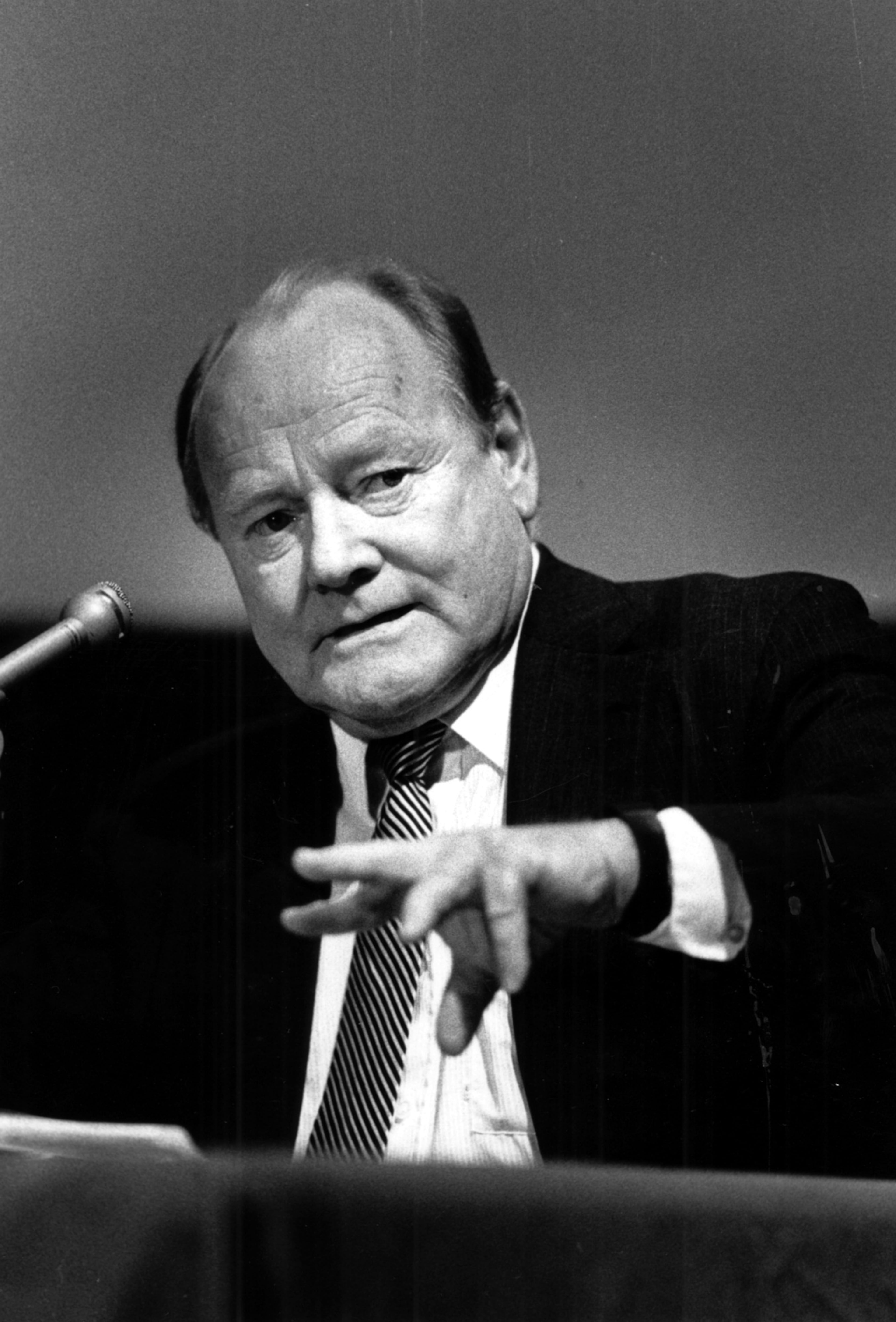

U.S. Rep.Sanford Bishop, D-Albany, served with Bond after being elected to the state Legislature in 1976. Bishop remembers Bond’s popularity with his constituents.

“I had the opportunity to go to Julian’s office. And when I got there, I had to wait. (There were) six or seven people waiting to talk with him,” Bishop said. “He was a celebrity. They were well-wishers. There were reporters. There were all kinds of folks that were there to talk with Julian.”

But, Bishop also remembers the difficulty Bond faced when passing legislation. Despite his national profile, some of those who refused to seat him still harbored resistance.

“Whenever a bill came across from the Senate that had his name on it, they would vote against it,” Bishop said.

In Atlanta, it confirmed that the city’s reputation for moderation had limits, when dissent crossed from the streets into elected office.

That, said Michael Julian Bond, is his father’s legacy.

“Education, activism, speaking truth,” Michael Julian Bond said. “Bringing people out of the darkness, whether that’s educational darkness, poverty or some other type of situation. You want to be a bringer of light and directional guidance to people to help them enjoy their own freedom. And I think that that’s his legacy.”

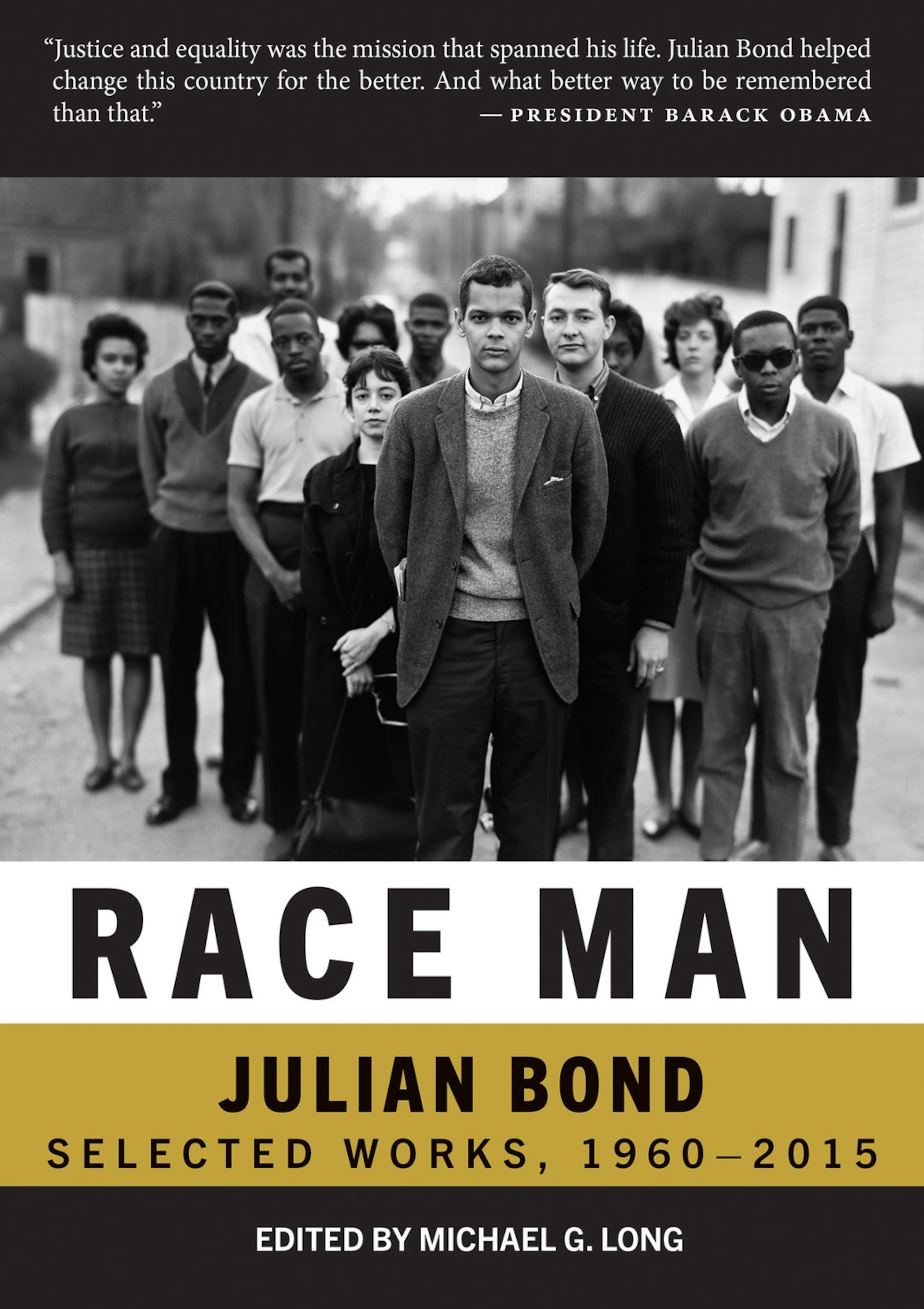

The aftermath of Bond’s ordeal stretched far beyond that single year. Bond went on to serve multiple terms in the Georgia House and Senate, helping organize the Georgia Legislative Black Caucus and pushing issues such as sickle-cell testing and housing access onto the state agenda.

Inside the Capitol, his influence extended well beyond floor debate.

Bond left the General Assembly in 1986 to run for Congress, losing a U.S. House of Representatives seat in a bitter race to his good friend John Lewis.

But he would later become the first president of the Southern Poverty Law Center and chairman of the NAACP, carrying his Atlanta-forged voice onto a national stage.

He appeared alongside Richard Pryor in the movie “Greased Lightning,” and in 1977, he even hosted Saturday Night Live. Bond died in 2015 at age 75.

“People should hear this story because you don’t give up,” Michael Julian Bond said. “Some people might have turned around and said, ‘Oh, well, you know, I don’t have time for this.’ Every time that the seat was opened up and he went for it again, it was a stand to say that ‘I matter.’”

AJC Washington Bureau Chief Tia Mitchell contributed to this report.

This year’s AJC Black History Month series marks the 100th anniversary of the national observance of Black history and the 11th year the AJC has examined the role African Americans played in building Atlanta and shaping American culture. New installments will appear daily throughout February on ajc.com and uatl.com, as well as at ajc.com/news/atlanta-black-history.